In Defense of the Weird

When I was in college, I visited Southeast Asia. On a routine shopping trip, I came across a pond in the mall where you could pay to have tiny fish eat dead skin off the bottom of your feet. Most of my American friends were utterly disgusted by the very idea. Those who did try it only did so to gain foreign-country bragging rights.

A similar feeling overtakes people when they come across “weird” stories.

Many say they can’t watch all of a foreign film because it was just too strange. Then there is the classic myth that Lewis Carroll was taking drugs when he wrote Alice in Wonderland. After all, how could a sane person write that?

What we cannot see in the everyday world is strange to us. When we encounter this strangeness, we are overcome by feelings of fear, distrust, and the desire to flee.

Average people are unaware of this phenomenon. But we can remedy this within our own hearts before we encounter The Weird. Tolkien addresses this issue sagely in his essay, “On Fairy-Stories”:

“I am thus not only aware but glad of the . . . connexions of fantasy with fantastic: with images of things that are not only ‘not actually present,’ but which are indeed not to be found in our primary world at all. . . . Fantasy, of course, starts out with an advantage: arresting strangeness. But that advantage . . . has contributed to its disrepute. Many people dislike being ‘arrested.’ They dislike any meddling with the Primary World. . . . They, therefore, stupidly and even maliciously confound Fantasy with Dreaming, in which there is no Art; and with mental disorders, in which there is not even control: with delusion and hallucination.”

Tolkien goes on to say these strange images of things outside our “primary world” are not only good, but virtuous. That’s saying a lot. How could he hold weird fairy tales in such high value?

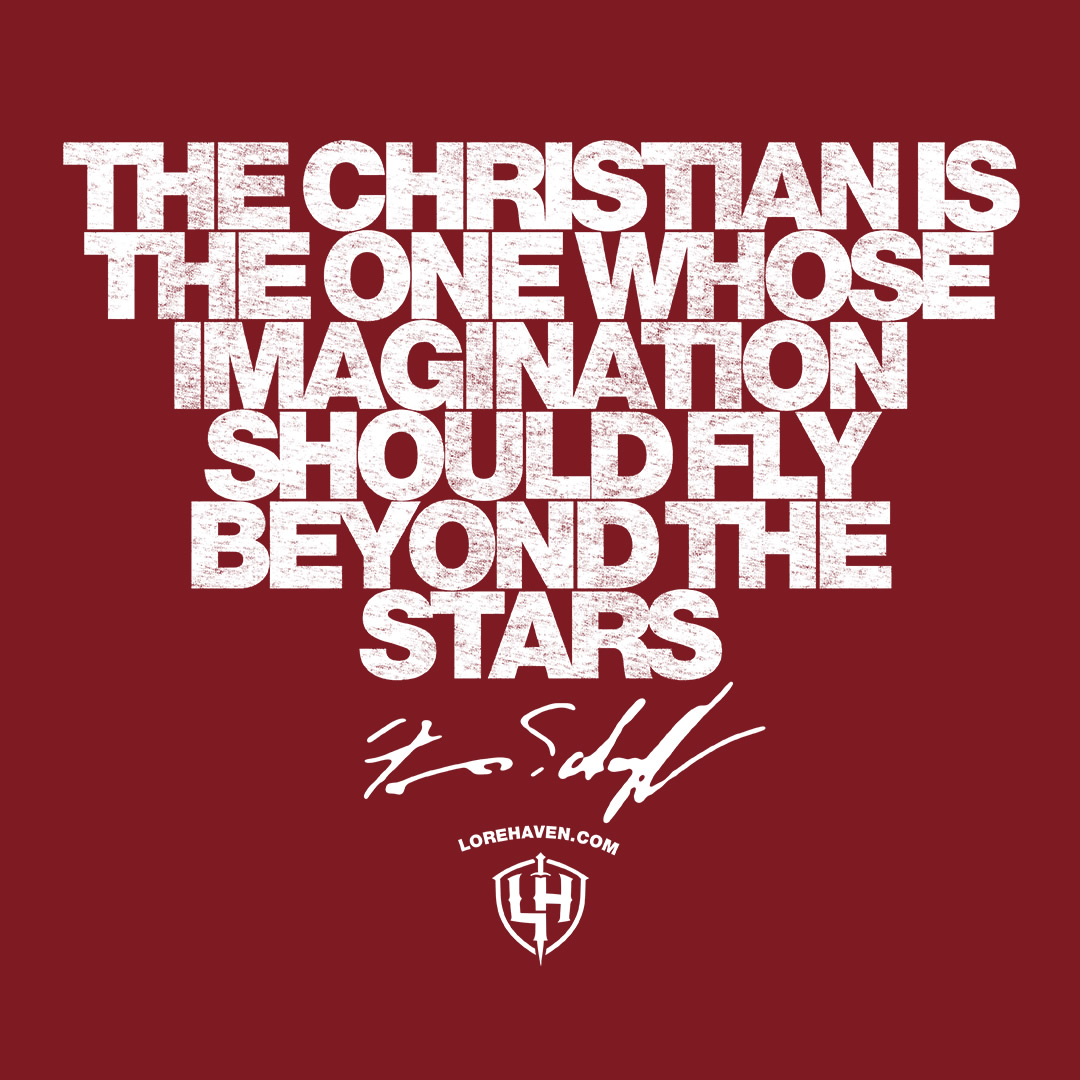

The answer is not based on these tales of fairies, monsters, or often dark and twisty themes. It’s based on the simple fact that God calls on us as Christians to believe in things not seen (2 Corinthians 4:18). Heaven and Christ in the flesh are invisible to us in this age. Yet our Lord calls us to live for these realities.

The Bible uses a myriad of people, stories, dreams, and metaphors to teach us about what we cannot see with our eyes. This is how God shows us his invisible nature and character. And much of the time, these images are strange and their meaning eludes us, such as the many visual metaphors used in Revelation or the Old Testament prophets.

In Romans 1:18–25, Paul says God’s wrath is revealed against the unrighteous who suppress the truth, that is, what can be known about God because of his creation. Since the beginning of the world, he shows us his “invisible” attributes through what he’s made. Mankind has no excuse not to believe, and yet they flee from him. “They exchanged the truth of God for a lie, and worshiped and served what has been created instead of the Creator, who is praised forever. Amen” (verse 25).

In this text, mankind flees from the invisible God, and toward what they can see in their primary world. They literally worship what has been created instead of the Creator, whose self-revealed truth just feels too weird—and even evil at times.

It is understandably tempting to feel safe in the known world, and not venture too far outside our own Hobbit holes. Yet, that is simply not the life God has called his people to live. When we encounter The Weird and are overcome by a sense of “arresting strangeness,” as Tolkien said, we should see this as a virtue to embrace.

The Weird is awkward, uncomfortable, and foreign. But that discomfort alone is not a sign that we should flee immorality. Instead, this sense only tells us that the weird thing exists outside our experience. To become more like our invisible God, we should become eager to learn. We should long to grow our imagination to the point that our discomfort lessens, or even disappears altogether. (The only exception would be if we also sense the Holy Spirit alerting us about a real moral dilemma.)

So, instead of avoiding those foreign books and films, watch them intentionally. An entirely different culture is a perfect place to find a little “arresting strangeness.” You can even grow your child’s imagination by showing them age-appropriate foreign films (like Studio Ghibli’s Ponyo, one of our family’s favorites).

Don’t just read science fiction and fantasy, but watch for authors who have powerful imaginations and surprise you with their ideas. Then, once you’ve found these people, read everything they’ve written.

But still more, pray that the Lord would give you a deep longing for the most important things outside our primary world: Christ and his kingdom.