Finding Truth in Science Fiction

I love science fiction.

From my earliest days watching Lost in Space reruns and reading comic books, science fiction, or sci-fi, has run in my blood. I like the stories’ “what if” nature, adventure, exploration, and worlds of endless possibilities.

You probably love science fiction too, even if you don’t know it.

We may assume science fiction is a twentieth-century phenomenon, a product of the space race, microchips, and Hollywood. But sci-fi elements have existed for a long time.

The eighth-century Japanese fairy tale of Urashima Tarō features time travel. The Arabian Nights, commonly known for its stories of Aladdin and Sinbad, also has stories of interstellar travel, lost technologies, and robotics.

Many literary classics have elements of science fiction. Gulliver’s Travels (1726) has weird science and alien cultures. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) features a mad scientist experimenting with innovative technology. So do later nineteenth-century novels, such as Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and H. G. Wells’s The Invisible Man, The Time Machine, and The War of the Worlds.

Venerated Christian authors wrote and still write science fiction. C. S. Lewis’s Cosmic Trilogy (also called the Space or Ransom Trilogy) has space travel, arcane science, and aliens. So does Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time. Stephen Lawhead’s Empyrion series and Kathy Tyers’s Firebird series are science fiction. I myself join many author friends in writing science fiction.

So, what exactly is science fiction?

Science fiction is better defined by its tropes—by its themes and plot devices—than by any rigid classification.

Does the story have space travel? Extraterrestrials? Science fiction. Time travel, future societies, parallel universes, or advanced experimentation? Science fiction, all.

The genre splits into two basic categories: hard sci-fi and soft sci-fi.

Hard sci-fi focuses on getting the scientific details right, specifically the natural sciences like physics, astronomy and chemistry. The story is presented as if it could truly happen someday and the reader may learn something along the way.

One recent hard sci-fi book (and movie) is Andy Weir’s The Martian. Other well-known hard sci-fi authors are Michael Crichton (Jurassic Park), Arthur C. Clarke (2001: A Space Odyssey) and Isaac Asimov.

Soft sci-fi leans toward the social sciences, such as psychology, economics, and sociology. But it’s better described as stories that focus on plot, characters and adventure with minimal regard for scientific feasibility. Two of my favorite soft science fiction writers are Ray Bradbury (The Martian Chronicles, Something Wicked This Way Comes) and Edgar Rice Burroughs (Tarzan and A Princess of Mars).

Either mode of sci-fi offers a plethora of different subgenres, ranging from popular to obscure. Often books straddle more than one subgenre, and occasionally some will defy classification altogether. But here are a few of the main subgenres:

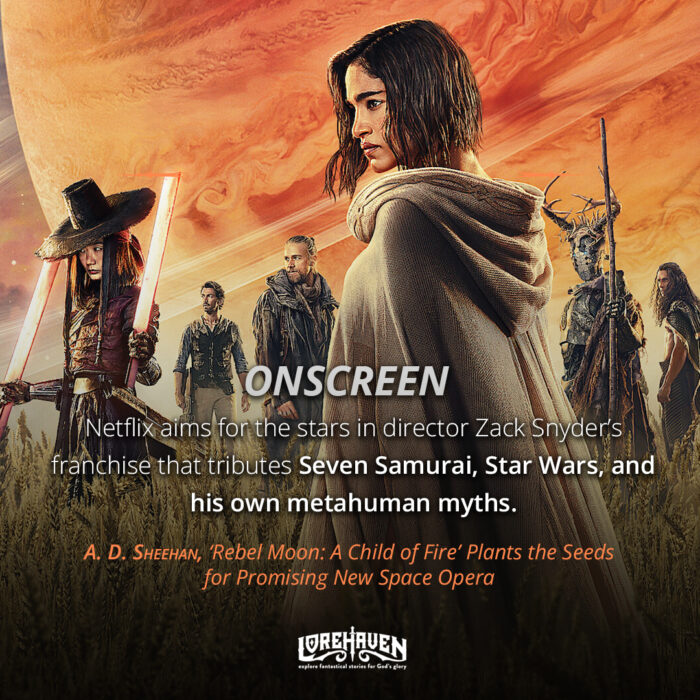

Space opera stories span multiple worlds, have diverse (possibly alien) characters, and lots of space travel. Their biggest defining feature is their scale. They are epic and operatic. Star Wars is a classic example, but also Frank Herbert’s Dune, Steve Rzasa’s The Face of the Deep series, and the Firebird series.

Dystopian stories focus on a future terrible society, usually one whose oppressive central government keeps the population enslaved. Classic examples are George Orwell’s 1984 and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. My novel Mask is dystopian, featuring a world where everything is subject to vote, including people’s right to live.

Time travel tales feature someone traveling from one time period to another. Early examples include Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court and Wells’s The Time Machine. Two recent examples are Michael Crichton’s Timeline, and Wayback by my author friend Sam Battermen.

Apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic dramas focus on a catastrophic event—nuclear war, plague, meteors, or zombies—and the human struggle to survive. For Christians, the Left Behind series by Jerry B. Jenkins and Tim LaHaye is considered apocalyptic. So is William R. Forstchen’s One Second After or Max Brooks’s World War Z.

Superhero stories feature figures with supernatural or metahuman powers. This is doubtless the most popular sci-fi subgenre right now. Superman, Batman, Wolverine, and the Avengers all live here. So do books by Christian authors, such as John W. Otte’s Failstate series and Adam and Andrea Graham’s Tales of the Dim Knight.

Cyberpunk presents a future of advanced technology, cybernetics, robotics, and heavy urbanization. Typically, the future is also dystopian or anarchical. The genre is popularly represented in movies like Blade Runner and The Matrix, and in books like William Gibson’s Neuromancer, Neil Stephenson’s Snowcrash, and Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One. My DarkTrench series has a heavy cyberpunk vibe. So does Kirk Outerbridge’s Eternity Falls and Frank Creed’s Flashpoint.

Steampunk’s technology is predominately steam-based—no electronics—with a styling and setting inspired by the nineteenth century. The Sherlock Holmes movies (with Robert Downey Jr.) have flashes of steampunk. So does the infamous movie Wild Wild West (with Will Smith). Christian novelists Morgan L. Busse (Tainted) and Steve Rzasa (Crosswind, Sandstorm) have both created popular steampunk novels.

Other subgenres worth exploring are alternate history (such as The Man in the High Castle), alien invasion (War of the Worlds), and robot fiction (I, Robot).

As a Christian, I find science fiction the perfect medium to explore greater truths. It gives us a chance to speculate about God’s creation and explore its purpose. Sci-fi also provides an excellent way to shine light on cultural trends by extrapolating them to their potentially dangerous ends.

Unfortunately, a fair share of science fiction today is written from humanistic and in some cases anti-Christian perspectives. But Christian writers like me hope to change this by crafting stories of exceptional quality and timeless truth.

I hope you’ll join me in this exciting adventure. The possibilities are endless.