Roundtable: Engaging Fictional Violence in Our Real Worlds

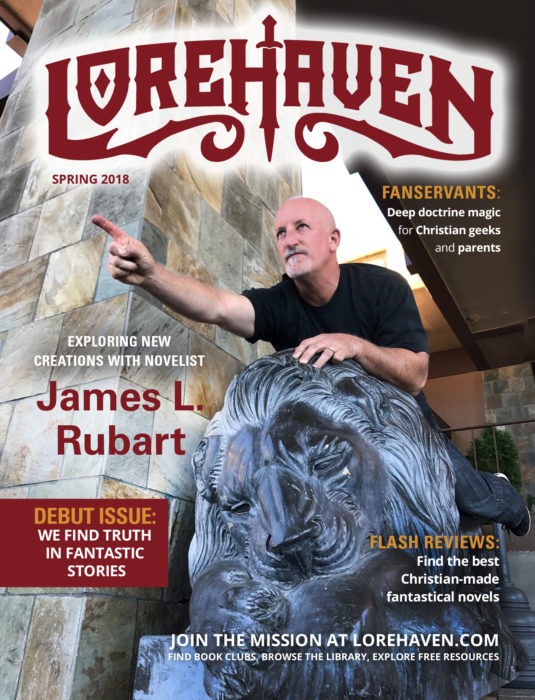

E. Stephen Burnett: As part of our mission, Lorehaven magazine will explore big issues helpful to Christian fans of fantasy and sci-fi stories. Today we’ll begin with one of four topics, which we’ll call the Four Horsemen of the Fiction Apocalypse. In particular order, they are violence, language, sex/nudity, and fictional magic.

Oddly enough, violence is actually one of the easier topics to address as Christians.

“Story violence” is the key phrase here. We’ll describe it like this: “Violent acts in a visual or written work of fiction.”

Of course, the Bible itself includes written references to violence. Our faith has a lot of violence in it. Interpretations vary as to how the violence is redemptive and how much God is involved with that. But Christians would agree: violence is part of this world, even though it doesn’t belong here.

However, just because the Bible has violence in it doesn’t mean we get to enjoy it in fiction. God has privileges that we don’t, and we have to proceed with care and discernment with those issues. So let’s explore this topic of story violence as biblical Christians and story fans.

We’ll also explore this with our differences and Christlike unity in mind. We have unity in Jesus, I believe. And the key verse here, and for every roundtable discussion we will have at Lorehaven in the future, is Galatians 5:13:

“For you were called to freedom, brothers. Only do not use your freedom as an opportunity for the flesh, but through love serve one another.”

1. What is the most violent act you have seen or read about in a story? How did this affect you? Did you make any changes in your story pursuits?

Carla Cook Hoch creates stories and edits fight scenes with Quill Pen Editorial.

Robert Liparulo

Robert Liparulo writes fantastical thriller novels, such as The Judgement Stone.

RobertLiparulo.com

@RobertLiparulo

Travis Perry serves in the Army Reserve and studies history and languages.

BearPublications.com

@BearPublication

Andrew Winch works as a physical therapist and edits Splickety Publishing Group.

Carla Cook Hoch: Robert Liparulo’s novel Comes a Horseman includes an act of beheading. But it is handled in a very good way, in that it is descriptive, but it is not gratuitous. You understand what has happened without adding sensory details that are so engrossing that it takes you off the point of what happens and directs it, rather, to the gross-out factor. So I really appreciated that.

For the most part, I don’t read very many books with violence. As far as what I’ve seen, I attend a gym where we do fight training. I have many friends who are fighters. It has given me a great amount of respect for humanity, because you see the humanity of someone in pain, and when you experience pain yourself.

Robert Liparulo: I do watch horror movies, and I’ve seen some extreme violence. I don’t like gratuitous violence. The violence has to have a very specific reason: to show the result of evil, or the level that we have to go to, to avoid violence being done to us, or to a loved one or somebody who can’t fight for themselves. But I don’t think that all the violence on the screens or all the violence in books are necessary.

Travis Perry: I’ve seen violence in person, and not just accidental violence. I’m also affected by historical accounts of violence, such as the the Battle of the Somme during World War 1—30,000 people killed in less than a day.

One fictional scene that pops up in my mind is the chest-buster scene in Alien. Alien portrays the universe as fundamentally hostile to humans. That’s what some people believe is true about the universe, that violence is natural. It’s not my view.

Andrew Winch: Like Robert, I’m a fan of horror. but I’ve found that I can’t handle cruelty. I don’t mind fantasy violence. I don’t mind fantasy wars. I don’t even mind monsters. But anything with human-on-human cruelty makes me physically nauseous.

As a physical therapist, blood and guts don’t affect me that much. I mean, I’ve had to study gross anatomy. I know what the human body is, as a creation of God. But it’s the reason for it, not necessarily the sight of it, or reading it, that affects me, anyway.

2. How do you feel about popular television series with violent acts?

ESB: One of the most infamously or famously violent stories on television right now is The Walking Dead. I’ve never seen that. However, one of the most violent visual shows I’ve ever seen is actually animated. It’s an anime series called Attack on Titan. It has really helped me imagine through some of this topic, just seeing what seems to be a very redemptive view of violence. And yet the violence is so visceral. I mean, there are these giant humanoid creatures that devour humans.

Travis: I was a fan of The Walking Dead. I enjoyed it because I thought it showed humanity at its worst, which I think is realistic. Humans go bad.

But there was a finale of a season, and the opener of the next season, where this character, Negan, beats two people to death with a baseball bat. I decided to stop watching The Walking Dead because of that scene, because it was gratuitous violence. It’s not entirely realistic. And the scene made me question if the show’s whole purpose is to desensitize people to violence.

Andrew: I still watch The Walking Dead. And I think that’s where different opinions comes in. I have conviction that I’m not necessarily supporting something evil if I continue to watch a show that, to me, still has a good overarching story.

These shows often have a rotating staff of different writers. So the story will become an amalgam of the personal beliefs of these writers. I think it’s obviously the viewer’s responsibility to know what those writers are pouring from their hearts into these stories. But for me personally, I still see enough redemptive qualities in the show.

But I agree: I think that that scene was written distastefully.

Carla: It was horrifying. Horrifying. And it made me sick and it made me cry.

But it also showed me that the story’s living people were on par with the dead. It showed how little respect they have for humanity and how little respect they had for life. There was actually not much difference between them and the zombies. This man knew exactly what he was doing, and he made that choice. It wasn’t about survival. It was about how he had lowered humans beneath zombies.

ESB: I understand this is a key theme in the show, and in other stories that arguably show violence in an almost Judeo-Christian view—violence doesn’t belong in our world.

When you say “gratuitous,” I hear you saying that the creators of a story seem to be saying, “Yes, violence belongs here. Isn’t it violent? Let’s just accept it and revel in the violence, because we’re just beasts at heart.” There’s no light to be seen, even from somewhere behind the camera, even if it’s not in the story itself.

Carla: I will say that as a woman, I have an especially difficult time with sexual violence against women and violence against children. I think that it can be handled in such a way that you still show the reality of something. Especially when you have stories based on reality, like the films Schindler’s List or 12 Years a Slave, if you don’t show the reality of it, you’re disrespecting what those people had to endure. But if you show too much, then the emphasis is on the gore of it, versus what these people survived.

You just have to know the author’s intention. As a reader, I can usually know whether the author’s intention is to serve the story, or to pique my interest in darkness.

“Violence [in fiction] has to have a very specific reason: to show the result of evil.”

— Robert Liparulo

Robert: I do think of my stories as both educational and entertaining. But when I write violence, I hope to depict evil for what it is. And it is a disservice to the reality that people face, when we either stylize violence or don’t show it. I’m not saying that it needs to be as gross and bloody as it can be. But I think when you see almost cartoon violence, that is insulting to the people who have to endure real violence.

In my novel The Judgement Stone, the owner of a privatized army desensitizes young soldiers by giving them a helmet that augments reality. So they think they’re fighting fictional people. The blood is blue, and everything is stylized cartoonish to get them to kill. And I think it’s wrong in fiction to depict violence in a cartoon way as well.

3. What is the most challenging objection to story violence you’ve heard?

Andrew: “You’re gonna make somebody stumble” (Rom. 14, 1 Cor. 8–10). Stories are very tricky. Because whose hands are they going into?

“You ought to read a story you’ve researched and are sure you’re ready to read.”

— Andrew Winch

But you ought to read a story you’ve researched and are sure you’re ready to read. You don’t just pick up a book and start reading. Same thing with a movie. Someone will look at a movie and say, “This probably isn’t something that’s good for my heart. I shouldn’t watch this.” They shouldn’t just say, “Oh, this got great reviews, I’m going to watch this.” They’re being irresponsible as a consumer and as a creator. In that respect, I think the burden falls on the person consuming more than the person creating.

Travis: I’m going to disagree with you a little bit. I think authors should ask: what will somebody think you approve of, by what you portray?

Similarly, I feel responsible as a soldier, because people think I know what war is like, and I think I do know what war is like. And I think that I am therefore obliged to portray it in a certain way, and I can’t just portray it in a way that I think is fun.

That’s not so much really the classic stumbling-block objection. But I don’t want people to think that I approve of something that I don’t. That, I think, is an important factor.

ESB: The apostle Paul says, “Do not let what you regard as good be spoken of as evil” (Rom. 14:16). That’s a good principle to keep in mind.

“If you make life too antiseptic, you discredit how difficult it is to be faithful.”

— Carla Cook Hoch

Carla: The objection I’ve gotten is, “Well what does light have to do with darkness?”

Here’s the thing: if you make life too antiseptic, you discredit how difficult it is to be faithful. You do a disservice to everyone who works very hard every day to be the person that God wants you to be, and let the Holy Spirit work in their life.

John Martin’s 1851–1853 painting The Great Day of His Wrath reflects God’s end-times judgment on the world. (Public domain)

4. How do you respond to the claim that ‘The Bible is full of violence’?

Robert: When I talk to creators who have created something that I think is gratuitous violence, often they’ll bring up the violence in the Bible. They’re absolutely right. I mean, you have people getting staked through the forehead. You have dogs eating everything but the palms of somebody’s hands. It’s very violent.

God shows us an example of the way to live, and that might include how to tell stories. And that might include violence in stories. However, some stories do present violence for violence’s own sake. In the Bible, violence is not treated as lightheartedly. It’s always used to show the consequences of sin and beyond.

“The Bible is very minimalistic about a number of descriptions, including of violence.”

— Travis Perry

Travis: A lot of times the Bible says things like, “Joshua smote the city with the edge of the sword,” and says nothing else. The Bible is very minimalistic about a number of descriptions, including of violence. And when you write a story, you have to give a little more than the Bible. It’s expected to give more. And certainly in movies, it’s almost impossible to give as little description as the Bible gives.

Carla: We’ve forgotten that we, in comparison, live in an antiseptic society. The Israelites killed their own food. They were people who had sacrificial blood sprinkled on them. What we consider to be violent probably isn’t what they consider to be violent. And they would come to our culture and see our pornographic media as more repulsive and repugnant than anything they encounter.

ESB: We’re also talking about an ancient society in which God himself instituted a violent sacrificial system, to do what I like to call “inception” in the minds and hearts of his people. God planted the idea without the shedding of blood, there’s no remission of sins (Hebrews 9:22). Every time you sin, one way or another, something had to die, and you had to smell the blood and you had to know: This is terrible. This is the penalty.

Without that violence, you would not have the redemption. You wouldn’t have the recognition of the truth when Jesus arrives as the final sacrifice, the final High Priest. He himself is the sacrificial lamb. He is himself slaughtered in the most violent act of barbarism in the history of the universe, and is victorious, so we don’t have to do that sacrificing any more. And that has no impact unless we knew that violence before.

“You can’t understand the full gospel of Jesus Christ without violence.”

— E. Stephen Burnett

You can’t understand the full gospel of Jesus Christ without violence.

So the concern about being gratuitous—that’s when acts of violence are separated from some kind of redemptive context. It is then exploitative, and you are not being realistic. Which is the same problem with an antiseptic story or an antiseptic view of reality.

One of my favorite quotes from The Screwtape Letters is where Screwtape is talking about violence and how considering violence can be escapism too. In other words, you can be all happiness and light and fluffy kitties and rainbows, and that’s escapism. But so is an undue emphasis on human remains plastered against the wall, while you’re assuming there’s no such thing as happiness or songs or joy in the world.

5. How can we address these objections in grace but also challenge them?

Carla: Part of what I don’t tell people about doing fight workshops is that I do come from a history of violence in the home. That is why God led me to this.

So there is a very redemptive quality for me because I am showing people: look where God has brought me. Early on, after my training, I was literally going back to my minivan, and crying and shaking, because I was terrified. Now, the fact that I am able to do all of this fight training speaks to the power of God. Because I have gotten beyond that place and not only am I beyond that place, but I can help other people come out of that place.

God did bring me there through faith and through his word. But he also brought me there through a couple of punches. And I think I got to the point to where I had to understand—God has made me unbreakable. Not physically. But spiritually? I’m not.

So I think sometimes the violence and that sort of thing has to be told.

ESB: It is kind of incumbent on the fan who feels strong in this area to help serve the “weaker” brother or sister in this area. And maybe refrain, but also show love to them, and make it clear: “I don’t believe reading or viewing this is wrong for me.”

Travis: I think it’s important is to promote stories that do violence the right way, such as the science fiction novel Ender’s Game. Was it necessary for humans to fight the Formics at the beginning? Of course it was. But humans go beyond what was necessary and try to wipe out the entire species. And then the hero Ender’s reaction to it—that’s a perfect way to show violence. That’s great! That’s the kind of story that I want to see.

I actually don’t meet a lot of people I feel have a problem with too much violence. I think I meet people who are too accepting of violence. So I’m trying to say, “Hey, let’s moderate this by being realistic about the consequences of violence.”

Andrew: We’ll use the idea of a teenager reading a book: consuming and digesting the story. The teen’s consumption of the story has a lot to do with the creator’s heart, method, and intention. How did they want the story to be perceived? Digestion comes from the kid’s preconceived notions, but also conversations that he has about that scene. Is he reading between the lines that the author never intended because of that reader’s own preconceived notions? So I think it is important to see the duality of that.

If you’re concerned about your teenager reading a violent scene, discuss that scene with them. Why did that happen the way that it happened? Was it okay? Was it not okay? What does that mean in the real world in their life?

ESB: Which presumes that parents are acting as servants and exploring popular culture and stories with their children, as their children are growing older.

6. How do we view story violence versus any necessary violence in reality?

Robert: There are times when violence is necessary, and the lack of violence, in my opinion, is disobedience to God. Because we are required to protect ourselves, our children, our families, and other people who can’t protect themselves.

Some Christians disagree with all violence, even at the point of protecting others or your own life. But I believe that God has asked us to protect ourselves because we love ourselves. God is clear that we love ourselves, because we are to love our neighbors as we love ourselves. If we don’t oppose somebody who wants to destroy or do violence to someone God created and asked me to protect, I am disobeying God.

Carla: When I talk about self-defense, people have said, “Well, God will take care of me.” And that is true. God will take care of you. He has created a home for you in heaven. Okay? God has the ability to fill the hillside with angelic warriors on horses. And sometimes he puts the sword in your hand.

If I am the temple of the Holy Spirit, if the Holy Spirit lives within me, then what are you doing when you harm my person? No one has a right to put harm on your physical person. Yes, the Lord may set that person on fire. He may also empower you to pick up your own hand and defend yourself. That does not make you less of a Christian.

Andrew: Personally, I would protect a loved one, and I would protect myself from being killed. But I have never been in a fight and I’ve never desired to be in a fight. I’ve been punched in the face, and I stood there confused. I’m just not a conflict person.

Violence for goodness’ sake is a very gray area, and varies from person to person.

Travis: I respect pacifists. That’s not my conviction. But I think there’s some good things about pacifism, because sometimes the real struggle isn’t physical, but spiritual.

ESB: “What’s it going to do to your heart if you’re involved in violence?” That’s what stories can help us work through. Even if we’re never in such situations, we must think about those things. Because, especially as Christians, we have brothers and sisters who are, say, soldiers, or working in emergency services, triage, or something like that. They go through these choices all the time. Fiction helps us to empathize with them. It helps us climb outside ourselves and imagine through these things as well as think through them logically. You have to do both. That’s one way that we worship our Lord and Savior—who eventually will make all of this violence, very joyously, a moot point. And he will make everything turn out redemptive in the end.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.