Netflix’s New ‘Frankenstein’ Reveals Why a Time-Shifted ‘Magician’s Nephew’ Film May Work

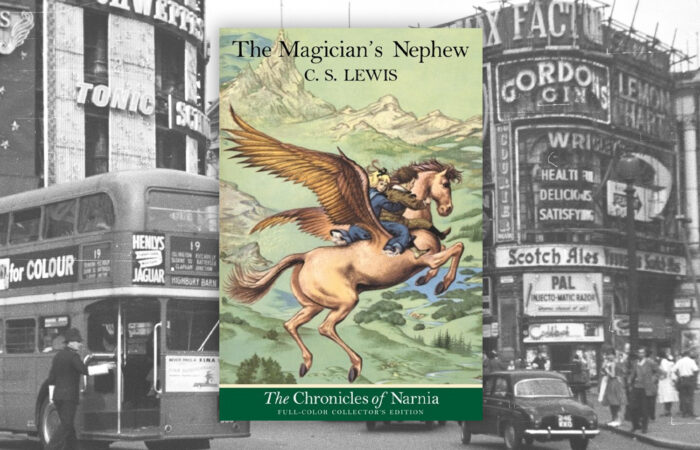

By now, fans who’ve long awaited Narnia movie updates know that Netflix’s film adaptation of The Magician’s Nephew (2026) is set in the 1950s instead of the 1900s.

Granted, no one associated with the ongoing film project has stated this explicitly. But the setting change is evident in casting call details and photos captured during on-location shoots in England.

Narnia fans have been scrambling to make sense of the rumor. After all, the novel was published in 1955. Maybe director Greta Gerwig has a cool meta concept up her sleeve—potentially with an actor playing C.S. Lewis narrating the film.

But photos have shown lead actors David McKenna (probably Digory Kirke?) and Beatrice Campbell (Polly Plummer?) filming scenes apparently set in post-World War II England rather than the Victorian era, making alternative explanations less likely. It’s increasingly obvious that Jadis will rampage around post–war London.

This, of course, opens a box of mysterious and messy ancient dust regarding the Narnia Cinematic Universe. What happens for a future screen adaptation of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe? Will the Pevensies flee New York City because of the Sept. 11 terror attacks? Will High King Peter have…a cell phone?

Gerwig has signed on to direct only one other Narnia project.1 What happens when another director comes in with a different creative vision? (Insert here a good number of words that would not look at all nice in print.)2

We could keep exploring why transplanting The Magician’s Nephew five decades beyond the book’s setting upends so many other canon events in the Narnia universe. But I want to entertain a more positive viewpoint.

Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein shows that time-shifting classics is not always bad

Recently I watched Guillermo del Toro’s long-planned adaptation of Frankenstein. This other Netflix film is nearly perfect and quite faithful to Mary Shelley’s classic, despite numerous departures from the source material. Shelley set her story in the late eighteenth century, and literary scholars agree that it spans just a few years in the 1790s. Del Toro’s Frankenstein is set sixty years later in the 1850s.

“The changes I made are numerous but always in service of this film,” del Toro said in one interview. “One was bringing the context of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars into the story. They were the backdrop to Shelley’s romantic movement. Lord Byron [who proposed the ghost story competition that sparked Shelley’s writing] actually rode through the battlefield of Waterloo.”

This new historical context plays into the movie in significant yet unobtrusive ways. I won’t recount all of them here, but our perceptions of a familiar story can be partly reshaped when that story is placed in a different historical in a new adaptation.

For instance, del Toro’s version shows the scientist Victor Frankenstein as less bizarre Victorian experimentalist and more post-Enlightenment scientist among scientists (and industrialists) testing the bounds of new capabilities. Much like the AI and robotics engineers of today, he pushes the borders of the possible based on what can be done, not necessarily what ought to be done.

This new era means the struggle of Victor’s Creature isn’t so much a hidden mystery. It’s documented and very present. Victor’s creation is harder to hide or handwave as a bump in the night. The monster is real, and it is with us.

Finally, del Toro’s Frankenstein takes place in the context of war and bloody European revolution. Death hangs in the air. The pursuit of death’s cessation (or death transformed into life) isn’t solely the realm of the solitary alchemist in his ivory tower. It is the concern of the general population.

“I didn’t want…you to feel that you were watching a classic interpreted with reverence,” del Toro went on, “but with urgency—and something alive now… The goal isn’t to sing the same song; it’s to sing it with my own voice…”

Some may not agree with del Toro’s incredibly personal philosophy toward adaptations, but he took Shelley’s Frankenstein and dropped it into a historical context Shelley barely lived to see and made it sing with old truth and new urgency.

Deep magic might continue in a time-shifted Narnia tale

I loathe the idea that we’ll get an adventurous adaptation of The Magician’s Nephew before we get a faithful one. However, the story is in the hands of a capable director. Gerwig is a proven visionary and has spoken openly about her love and reverence for Narnia and her desire to adapt the story “correctly.”

Del Toro’s Frankenstein works because it doesn’t abandon the heart of Frankenstein: the enduring questions of scientific ethics, the immortal desire to overcome death, and man contending with the woebegone aftermath of his own work. Everything that anchors Frankenstein is still there, couched in a context that breathes new life without turning it into a modern tale.

We could argue over the critical elements of The Magician’s Nephew. What makes this story so good? If a 1950s time-shift precludes Strawberry from being an ordinary cab horse, is the tale robbed of something essential? If Jadis isn’t impressively balancing atop a hansom cab, is something important lost?

Such specifics may not matter as much in the realm of adaptation. A deeper magic, a magic that transcends time, runs through the Narniad. That’s why the books remain relevant and why Netflix paid a pretty penny to adapt them.

Aslan gives the children a particular warning at the end of The Magician’s Nephew: that our world “will be ruled by tyrants who care no more for joy and justice and mercy than the Empress Jadis” and “that some wicked one of [our] race” might “find out a secret as evil as the Deplorable Word and use it to destroy all living things.”[C. S. Lewis, The Magician’s Nephew.] had the benefit of hindsight to make his warning specific to a world reeling after World War II. That warning rings as relevant today as it was in 1950 (or as it would have been in 1900).

A true tale, and any good Narnia adaptation, must account for the influences of what Gerwig calls “really old story forms”3 and “larger universal truth behind what are so-called ‘small’ lives.”4 New adaptations must embrace the deep magic found in old stories and myths, biblical parables, and persistent archetypes.

The soul of Lewis’s Narnia tales applies to any time and any timeline, embedding the same capital-T truths that would appear whether he wrote them in 1900, 1950, or the early 2000s.

However The Magician’s Nephew adaptation turns out, I hope it appeals to the general population perhaps even more than to die-hards like me. I want newcomers to Narnia to go running to the books for more deep magic. After all, no adaptation of a beloved story can ever match reading the book for the first time.

- This fact is far more troubling to me than the unconfirmed time-shift, because it makes me think Netflix has no overall plan for the property they bought rights to for “slightly less” than $250 million. ↩

- My heart’s desire is for Gerwig to adapt The Horse and His Boy. It is also the one book least likely to be affected by a time-shift of any of the other books. ↩

- In this Associated Press interview, Gerwig talked about some of the influences in Barbie. ↩

- Michael Whale, “Lady Bird’s moments of grace,” Angelus News ↩

Thank you for writing this article. Everything you said resonated with me. I am warried by the direction Greta is taking the Narnian timeline, but I am willing to not judge a book by its cover. I am more concerned that Netflix fired the man who was working on an overall “Cinematic Universe” for Narnia at Netflix (even though it sounds like he had some even wilder and more outrageous ideas that Greta) and are only committing to one–maybe two–films. I was really hoping that Netflix would give Narnia the “A Series of Unfortunate Events” treatment and adapt the entire seven-book series into a streaming show composed of perhaps twenty episodes. The entire series would benefit from the same actors for the grown-up Pevensies reprising their roles in The Horse And His Boy, and The Voyage of the Dawn Treader really should be a series of seven half-hour episodes.