‘On Magic and Miracles’ Trains Christians to Dispel Darkness and Discern Fantastic Stories

Lorehaven creators didn’t start the evangelical clashes over fantasy. Neither did the first Harry Potter book published in June 1997. This big question—is it sinful for Christians to enjoy fictional stories with “magic”?—has challenged us for decades.

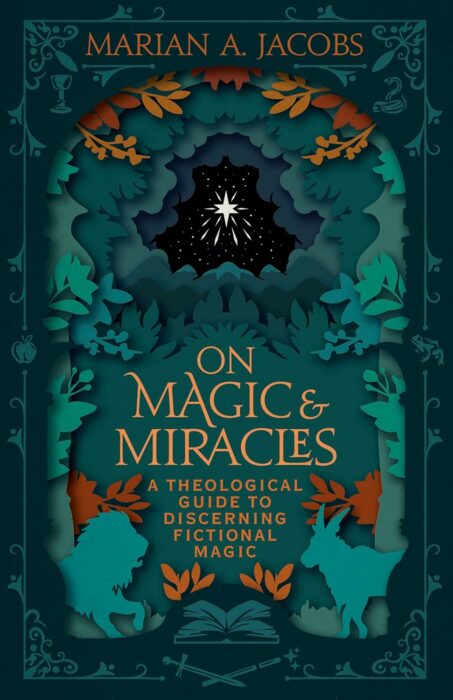

Marian A. Jacobs’s new nonfiction-about-fiction book On Magic and Miracles crafts a true and joyous grand finale to evangelicals’ longtime debates over fictional magic.

Christian fantasy fans will be challenged and encouraged. Christian fantasy skeptics will find biblical rationality, not just feelings, as the foundation for convictions about these stories. And nonbelievers may see vindication for their rising awareness of evil, yet be challenged to pursue Christ rather than enchantment-for-its-own-sake.

And for myself, having read the book twice (draft and then final), I recalled no few memories of my own lifetime wrestling with biblical truth and fantastic imagination.

Some Christian kids lived a non-magical childhood

When I was a kid, magic was all over 1980s cartoons. I never watched the stuff. Yet I somehow got wind of it anyway, and started giving my own stuffed animal-based characters this ability (mainly little drawings of these critters firing yellow zaps out of their hands to make stuff happen). I can’t recall when a parent got onto me. But one way or another, I felt bad about the creative choice and quit.1

A whole generation of Christians have faced this challenge, and often heard strong warnings from evangelical leaders in broadcasts or articles as well as in person:

- “It’s a sin,” insisted “Wretched Radio” host Todd Friel in a 2011 radio episode. “Deuteronomy 18. God hates that stuff. I’m not going to ingest that stuff, nor am I going to let my kids [ingest it].”2

- “You must protect your children and grandchildren, therefore, from the occult evils promoted by the Harry Potter books and movies,” wrote MovieGuide founder Dr. Ted Baehr. “This kind of fiction poses all kinds of dangers for your children and teenager [sic]. … It is a dangerous gateway to the occult that could entice your child and grandchild away from Jesus Christ and put them under the spell of Satan and his demonic minions. Beware!”3

- “Best avoid that stuff,” says your own earnest pastor or godly relative. “It could be demonic, or you could end up making someone out there stumble into temptation.”

Even after we enter the Narnia/Tolkien/Harry Potter phase(s), we may be haunted by those old answers that we may now consider legalistic rules. Alas, in response to those negative associations, we may fall into opposite temptations.

We could minimize Scripture’s serious calls to holiness.

Or ignore the real threats of demonic influences in our world.

Some may even drift into functional materialism, claiming that of course we believe in Satan and spiritual warfare, but in practice acting like these don’t exist.

Satan is real and Christians must dispel his darkness

With equal parts compassion and conviction, Jacobs guides readers into a survey of the real concern Christians have about fictional magic—that it’s inevitably a gateway drug to real involvement with demons. What about purity? What about holiness?

Jacobs takes these seriously, but rightly insists on foundational work. Going straight to applications would be putting the magician’s cart before the flying horse.

First she seeks biblical definitions for magic and miracles. Contra some Christians of more academic or so-called practical bents, we cannot simply claim “magic isn’t real,” Jacobs notes (page 14). Satan and his legions do have counterfeit power that extends to the physical realm, based first on biblical accounts about sorcery yet also newer accounts of demonic “miracles.” Some occult followers today may even have the ability to sense their connections with evil spiritual influences “jammed” by a Christian’s mere presence, as Jacobs shares in a personal example (pages 73–74).

Moreover, Jacobs writes, we must take seriously and rightly define the exact evils posed by contemporary occult practices. Here she avoids delving too deep and greedily into the unfruitful works of darkness, but rather exposes them.

Lest this seem familiar stuff for some readers, behold a twist: In watching nigh-200 testimonies by former New Agers, Jacobs found that barely a dozen “mentioned fantasy magic as part of their journey, and only 1.5 percent mentioned Harry Potter specifically. Out of those eleven people (5.5%), the primary reason people were drawn to the New Age was either trauma or mental health problems” (page 186).

That finding alone must provoke Christian skeptics of fictional magic to question their assumption that such stories only serve as gateway-drugs to occult practices.

And lest readers (like myself) feel wary about excessive warnings of demons, Jacobs covers all the bases of human responsibility. Yes, Satan and his folk are powerful, but can only work with our sin-natured raw material. No one gets to claim “the devil made me do it.” Yet we’d do well to remember that rebellion (as bad as divination) often follows suffering, leading to cravings for demonic promises that end in death. The right response to real “witches” is not fear and rage, but godly compassion—and rejoicing that our infinitely powerful Savior can break any lies that He chooses.

Jesus defeats devils and helps us find great fantasy

On Magic and Miracles also keeps constant vigilance against some Christians’ habit of being so obsessed with what Satan’s doing that we hardly see the gospel’s power as reflected in redemptive stories, both true and fictional. Starting in chapter 7, Jacobs turns from darkness to light. Now readers can see better to make practical applications, starting with a quick and careful debunking of bad evangelical rules.

From what she calls “minority rules legalism” (the canard of someone out there could use your enjoyment to sin) to “just in case legalism,” each fantasy-fiction skepticism gets busted—always as an act of Christlike love. Here is wisdom for the Christian fan who may never have reckoned with those well-intended calls to holiness, but instead effectively dismissed holiness as legalism. But here also is a reminder to another group Jacobs identifies. I share her respect yet also challenge for them:

I’ve witnessed Christian parents join social media groups and request book recommendations with zero violence, magic, fantasy characters, rule-breaking, or romance. They aren’t looking to avoid books that specifically glorify these things; they’re looking to avoid them altogether. Although there may be times when those need to be restricted depending on the circumstances and age of the child, avoiding all of these all the time removes the need for critical thinking, development discernment, and the discipling of a child through the real world.4

Yes, On Magic and Miracles touches on hot topics such as parenting and of course that controversial boy wizard. (Chapter 12 engages with the Harry Potter subject in a hyper-useful and nuanced manner that I believe some early-2000s evangelical Potter alarmists and Potter cheerleaders should have been doing all along.)

But readers would be remiss in considering On Magic and Miracles, like any novel, as just a book about how we handle the kids. Fictional magic pervades everyone’s life because God has made a supernatural world. Adult imaginations (and thus our stray beliefs, games, memes, songs, and stories) can’t help but reflect this reality. So unless we rightly “read” God’s supernatural world according to the Bible, we’ll not rightly read supernatural accounts or fictional magic according to His wisdom. In fact, if we dismiss the truth about real supernatural activity and fictional magic’s differences, we’ll likely fall into magical thinking about faith, conspiracies, or culture.

On Magic and Miracles should really mark the last word in Christian debates over fictional magic. Any more anti-fantasy memes spread by well-meaning aunts or tradvangelical podcasters must be answered with the biblical wisdom spelled in these pages. Perhaps in light of On Magic and Miracles and the real-world personal holiness this book may help restore, Christian fans can put behind our old ungodly fears as we enjoy Jesus-exalting fantastical fiction in light of our Author.

- From then on, The Animals would only use technology. Better fiction-magic-evasion through sci-fi! ↩

- Todd Friel, “Wretched Radio” episode dated July 19, 2011, accessed via private archive. ↩

- “Protect Your Children from HARRY POTTER Occultism,” Dr. Ted Baehr at MovieGuide, ↩

- On Magic and Miracles: A Theological Guide to Discerning Fictional Magic, Marian A. Jacobs, page 190 (B&H Publishing). ↩

Share your fantastical thoughts.