An Apologetic Of Horror, Part 3

SOCIAL COMMENTARY

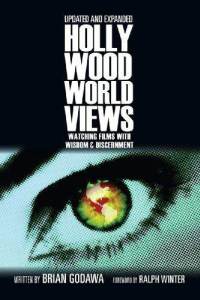

Lastly, the horror and thriller genres can be effective social commentaries on the sins of society. Many Christians claim that we should not tell stories that focus on the evils of sin. They appeal to verses such as Ephesians 5:12: “It is disgraceful even to speak of the things which are done by [the sons of disobedience] in secret.” I write about this “hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil” interpretation in my newly updated and expanded edition of Hollywood Worldviews: Watching Films with Wisdom and Discernment. These critics read this Bible verse, and others, to teach that we should not speak of, let alone watch, acts of depravity in movies. But look at the verses before and after this “disgraceful to speak” verse. Ephesians 5:11: “Do not participate in the unfruitful deeds of darkness, but instead even expose them.” Ephesians 5:13: “But all things become visible when they are exposed by the light, for everything that becomes visible is light.”

Lastly, the horror and thriller genres can be effective social commentaries on the sins of society. Many Christians claim that we should not tell stories that focus on the evils of sin. They appeal to verses such as Ephesians 5:12: “It is disgraceful even to speak of the things which are done by [the sons of disobedience] in secret.” I write about this “hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil” interpretation in my newly updated and expanded edition of Hollywood Worldviews: Watching Films with Wisdom and Discernment. These critics read this Bible verse, and others, to teach that we should not speak of, let alone watch, acts of depravity in movies. But look at the verses before and after this “disgraceful to speak” verse. Ephesians 5:11: “Do not participate in the unfruitful deeds of darkness, but instead even expose them.” Ephesians 5:13: “But all things become visible when they are exposed by the light, for everything that becomes visible is light.”

Paul is not telling us to evade talking about deeds of darkness because of their disgracefulness; rather, he is telling us to expose them by talking about them. By bringing that which is disgracefully hidden out into the light, we show it for what it really is. This proper biblical use of shame aids us in the pursuit of godliness.

This is exactly the tactic God uses with his prophets under both Old and New Covenants. God uses horrific explicit images in order to put up a mirror to cultures of social injustice and spiritual defilement. God used gang rape of a harlot and dismemberment of her body as a metaphor of Israel’s spiritual apostasy (Ezek. 16 and Ezek. 23), and the resurrection of skeletal remains as a symbol for the restoration of his people within the covenant (Ezek. 37). Our holy, loving, kind, and good God also used the following horror images to visually depict cultural decay and social injustice: skinning bodies and cannibalism (Mic. 3:1–3); Frankenstein replacement of necrotic body parts (Ezek. 11:19); cannibalism (Ezek. 36:13–14; Ps. 27:2; Prov. 30:14; Jer. 19:9; Zech 11:9); vampirism (2 Sam. 23:17; Rev. 16:6); cannibals and vampires together (Ezek. 39:18–19); rotting flesh (Lam 3:4; 4:8; Ps. 31:9–10; 38:2–8; Ezek. 24:3, 33:10; Zech 14:12); buckets of blood across the land (Ezek. 9:9, 22:2–4); man-eating beasts devouring people and flesh (Ezek. 19:1-8; 22:25, 27; 29:3; Dan. 7:5; Jer. 50:17); crushing and trampling bodies and grinding faces (Amos 4:1; 8:4; Isa. 3:15); and bloody murdering hands (Isa. 1:15, 59:3; Mic. 7:2–3). Horror is a strongly biblical medium for God’s social commentary.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers is a story that has had many movie remakes, with all of them reflecting the current cultural fears of each era. The basic template is a story about an epidemic of alien life forms coming to Earth and replacing human bodies with people who look the same but are part of a conspiracy to take over the planet. The original (1956) was a political analogy of the Red Scare of communist infiltration of the United States in the 1950s. The 1978 remake, starring Donald Sutherland, was a parallel to the 1970s conformity to the herd mentality of the New Age “me decade.” Body Snatchers was the 1993 version that analogized the doppelganger takeover to a monolithic conformism to U.S. “military imperialism,” with a touch of AIDS paranoia thrown in. In 2007, The Invasion, with Nicole Kidman, became a parable of cultural imperialism and the postmodern “other.”

Strong social criticism has been leveled by horror movies at various relevant issues in our culture. In Underworld, racism is paralleled and condemned through an “inter-species” romance between a werewolf and a vampire; The Wicker Man, damns neo-pagan Gaia religion in its murderous matriarchal colony of goddess-worshipping, man-abusing feminists. In one segment entitled “Dumplings” in the movie Three Extremes, abortion is likened to the sci-fi quest for eternal youth through cannibalizing our offspring.

One common theme in some horror movies is the degeneration of society into a selfish survival of the fittest ethic that animalizes us, versus an ethic of self-sacrifice that humanizes us. In a sense it becomes a cinematic dialectic of the evolutionary worldview versus the Christian worldview.

28 Days Later is about Jack, who awakens in a hospital bed to discover all of London is empty of people—except for roaming zombies seeking human flesh. The zombies are the result of a viral contagion that sends people into a murderous rage. When Jack stumbles upon a fortress of military survivors besieged by the zombies, this isolated human society degenerates into its own animalistic survival. It is a parable of how uncivilized male aggression can become an evil culture of “zombies within.”In the sequel, 28 Weeks Later, a father struggles with the moral guilt of saving himself at the expense of his wife’s life when escaping from the zombies. He finds it hard to face his own surviving children later. The entire movie is an incarnation of the ethic of survival versus the ethic of sacrifice, the first making us no different than a zombie, the other making us human. Those in the movie who try to save themselves tend to end up stricken; those who try to rescue others at risk to themselves demonstrate the potential nobility of the human race.

I Am Legend is a parable of a lone survivor, Neville, maintaining his humanity in the face of wild flesh-eating zombies. It becomes a Christ parable as Neville’s blood contains the antibody to the viral contagion that caused the zombies in the first place. As a Christ figure, Neville must sacrifice himself to save others, but only after struggling with his doubts about God’s goodness in light of all the evil. A fellow survivor’s unwavering faith that “God has a plan” wraps up this movie that wrestles with God’s sovereignty and evil, the primal instinct for survival, and the values of religion, sacrifice, and atonement.

30 Days of Night portrays vampires as metaphors for an atheistic evolutionary survival of the fittest ethic. When one victim whispers a prayer to God for help, the head vampire stops, repeats the word, “God,” looks all around the heavens to see if He will answer, and then replies very simply, “No God” before devouring her.

It is important to remember that in a story, the worldview that the villain holds is the worldview that the storyteller is criticizing. So the fact that the vampires in this movie are atheistic, inhuman predators without mercy is a metaphor for the consequences of evolutionary ethics. In contrast with this ethic, the people who do battle with them can only win by being more human, which is through altruistic sacrifice of themselves for others.

DISCERNING GOOD FROM EVIL IN GOOD AND EVIL

Horror and thriller movies are two powerful apologetic means of arguing against the moral relativism of our postmodern society. Not only can they reinforce the biblical doctrine of the basic evil nature in humanity, but they can personify profound arguments of the kind of destructive evil that results when society affirms the Enlightenment worldview of scientism and sexual and political liberation. Of course, this is not to suggest that all horror movies are morally acceptable. In fact, I would argue that many of them have degenerated into immoral exaltation of sex, violence, and death. But abuse of a genre does not negate the proper use of that genre.

It would be vain to try to justify the unhealthy obsession that some people have with the dark side, especially in their movie viewing habits. Too much focus on the bad news will dilute the power that the Good News has on an individual. Too much fascination with the nature and effects of sin can impede one’s growth in salvation. So, the defense of horror and thriller movies in principle should not be misconstrued to be a justification for all horror and thriller movies in practice. It is the mature Christian who, because of practice, has his senses trained to discern good and evil in a fallen world (Heb. 5:14). It is the mature Christian who, like the apostle Paul, can explore and study his pagan culture and draw out the good from the bad in order to interact redemptively with that culture (Acts 17).

– – – – –

Brian Godawa is the screenwriter for the award-winning feature film, To End All Wars, starring Kiefer Sutherland and Alleged, starring Brian Dennehy as Clarence Darrow and Fred Thompson as William Jennings Bryan. He previously adapted to film the best-selling supernatural horror novel The Visitation by author Frank Peretti for Ralph Winter (X-Men, Wolverine).

Brian Godawa is the screenwriter for the award-winning feature film, To End All Wars, starring Kiefer Sutherland and Alleged, starring Brian Dennehy as Clarence Darrow and Fred Thompson as William Jennings Bryan. He previously adapted to film the best-selling supernatural horror novel The Visitation by author Frank Peretti for Ralph Winter (X-Men, Wolverine).

His book, Hollywood Worldviews: Watching Films with Wisdom and Discernment has been released in a revised edition from InterVarsity Press. His new book Word Pictures: Knowing God Through Story and Imagination (IVP) addresses the power of image and story in the pages of the Bible to transform the Christian life.

His new Biblical Fantasy novel, Noah Primeval will be released next month. Visit his web sites to read sample chapters and learn more about Brian.

Brian, thanks for doing this series. I especially appreciate the way you support your views from Scripture.

I will say, however, that some of the things you call Biblical horror — examples of vampirism for instance — I’ve never viewed in that way because it is metaphor. In addition some of the true stories of Israel’s sinfulness are horrific, but again I’ve never equated that with horror. Maybe it has to do with my definition of horror. I associate it with generating fear.

I especially appreciated the closing of this 3-part apologetic:

All that being said, I find myself no more inclined to read horror. I’ve tried of late, reading a number of Christian supernatural suspense/horror stories. While I may see redemptive elements in them, I have no desire to live in that darkness for all those pages. It’s just not the kind of story I care for.

I’m wondering, then, if the “too much focus on the bad news” that you mentioned above is a subjective thing. What is “too much” for one person, is a drop in the bucket for someone else.

Looking forward to your fantasy coming out in November.

Becky

Becky, you wrote:

“I’m wondering, then, if the ‘too much focus on the bad news’ that you mentioned above is a subjective thing. What is ‘too much’ for one person, is a drop in the bucket for someone else.”

I have a very gentle friend who reads Christian supernatural suspense/horror stories. She sees all the spiritual implications and is fascinated, always relating what she finds to the Bible. I read or watch it sometimes, but I have to be ‘sure about it’ before, if that makes sense.

Fair enough. I always tell people I am not trying to make them horror fans because each genre requires a certain type of subjective inclination. I am only trying to open minds to whatever level I can. I think you are right that it is a subjective thing. My wife cannot read or watch my novels and movies, but I don’t judge her. They’re not for everyone.

Brian, sometimes we can be surprised by just who has this inclination to appreciate the genre. It isn’t for everyone, believer or unbeliever–you’re right. My husband, who can watch war movies that are explicit in their violence, can’t endure any film that depicts vampirism. Personally, I admire his good taste. However for me, if the vampire movie is a serious one, and vampires are depicted as evil entities that cower at the Name of Christ, I can appreciate it.

Interestingly, Bram Stoker’s Dracula (while too sexually explicit and over the top on imagery) inspired an evocative, beautiful film score that helps me write fantasy/fairytale fiction. (I still have to take a look at Dracula 2000, as you suggested elsewhere. )

Brian, you gave significant interpretations of several horror films, showing their true ‘souls’. These are intriguing and valid.

Perhaps the good to be gained from this genre of fiction or film is twofold. For unbelievers, it provides the opportunity or the eyes to see this present evil age for what it is. For believers, viewing the best ones affirms all that the Lord reveals about who we are and what we’re capable of, without Him.

The genre, when carefully done, is good medicine. But we should dose only according to the directions on the label. The directions should read: “Small doses, only as needed. In the case of accidental overdose, please contact your local Poison Control Center. And, as with all medicines, keep out of the reach of children.”

Clever. I like that. I guess it’s the same with the Bible as well. We don’t read Ezekiel 16 or 23 or even Revelation or most of Judges to children until they are old enough to understand. Same with the sexuality of Song of Solomon.

Very true, Brian!

Hey, I just found these (thanks to a helpful link dropped by Becky :p). Great stuff. I’ve been saying these things for longer than I care to admit and it’s been a real treat seeing someone else say them too. I am not alone! 🙂

Great, great thoughts, Brian, and I think you’re dead on.

Becky, I think what you said about “having no desire to live in that darkness for all those pages” is interesting. I think, to a large extent, the “too much” you described is subjective. I’m a horror writer/fan/afficiando (as you’re already well aware :p), but “scary movies” don’t scare me. I find them to be a welcome break from real-life scary things. I think they’re thrilling–even suspensful (but in a fun way)–but fear stems from a loss of control and I know that I’m always in control of a movie in the sense that I’ve got the remote in my hand and can switch it off when I get bothered. Some movies disgust me, yes, and those I don’t like and don’t watch.

I watch vampire/werewolf/monster movies and I don’t see darkness. I just see childlike wonder :p I see fantasy talking about things that I fear in my real life but don’t want to talk about. It’s all code for things that are too tough to face head on.

I see something like Hostel (or parts of it–I couldn’t sit through it) though–human on human cruelty–and I see darkness and I don’t want anything to do with it. So, maybe, like you, I don’t like to “live in that darkness” either–it’s just my darkness-meter and yours are adjusted differently.

Kindred spirits! I appreciate your insight, Greg. Your explanation reminds me of Bruno Bettelheim’s explanation of fairy tales and their brutality of witches eating children etc. as a code to introduce children to their mortality and thus come of age. This is because real life evil is far too difficult to face head on.

This series was great! I just wrote a similar blog post, so this really resonated with me. I totally agree with most of the comments, as well. Horror, like all other genre’s can be abused, but can also be used to honor God. Thanks for taking the time to put this up!