Why Do We Need Christian Fantasy?

Some readers of last week’s Why Isn’t There More Christian Fantasy? shared this response:

Well, why do we need “Christian fantasy” anyway?1

Others frequently discuss how fans should stop looking for any “Christian” label.

They say, “I don’t like/write ‘Christian fantasy.’ I’m a Christian who likes/writes fantasy.”

This implies: We should not have “Christian”-labeled, -categorized, and -marketed stories.

Behind that idea is this argument: Christians are meant to be in the world. We should not separate from the real world in our little churchy enclaves. Also, our cultures of Christian stores and media are so saturated by Amish fiction, Adverb Romance, and dumb stuff. So: shouldn’t Christian fans of fantastical stories ignore “evangelical culture” and join the real world, including non-specifically Christian stores and stories?2

I’m sympathetic to this approach. But I also heartily disagree with it.

I believe we need Christian cultures and subcultures of Christian stories and songs.

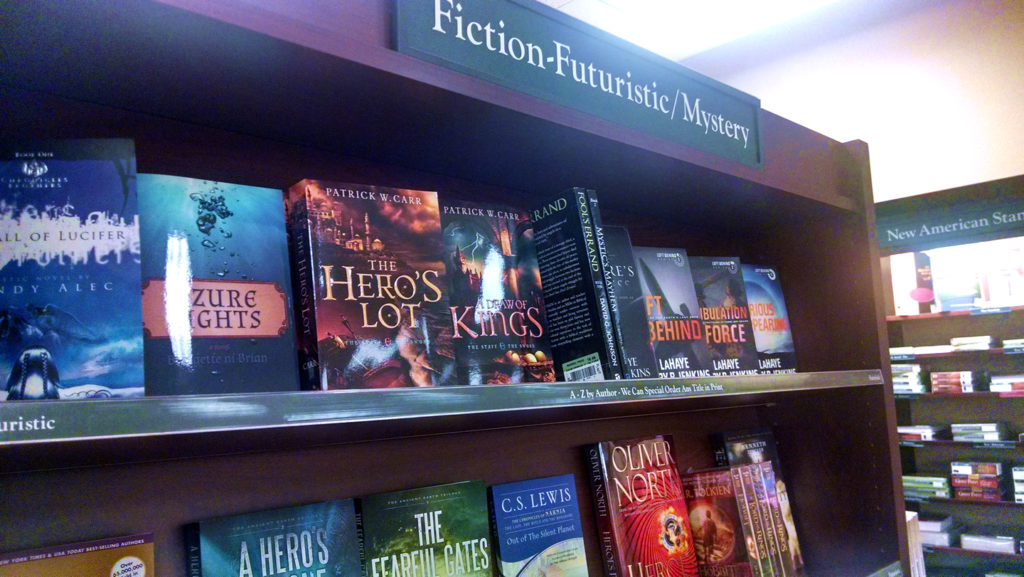

This includes “Christian fantasy”—fantastical novels by and (mostly) for Christian fans.

I support the label, the subcultures, the marketing, and even those corny little bookstores.

Here are six reasons why.

1. Christians get to have our own cultures too.

Everyone else gets to have and embrace a “culture,” however lame it is. But Christians seem uniquely embarrassed to have one at all. Think of it: Cancer survivors, single moms, pet lovers, and gamers have groups and arguably “insular” gatherings. They have their own literature, articles, and subcultures of references, jokes, jargon, and recognized leaders.

Why should Christians feel it’s wrong to enjoy the same blessing of human subcultures?

Popular culture is human stories and songs. All humans have these. A “subculture” is a smaller piece of culture among a smaller set of humans. All humans have these too.3

Christians, don’t feel guilty just because your subcultures exist.

2. Jesus does call Christians to be ‘separate’ in a way.

Plenty of churches and Christians act like naïve children or worse, mean-girl cliques.

But that’s no call to reject Jesus’s call. He calls his people a chosen priesthood, a group of separate individuals acting as one Church.4 This means Christians are called to be different from other people. This is not for the sake of “being different” alone. (What would that even mean?) It’s for the sake of being like Him, the God Who saves people.

3. Christian cultures can be ‘redeemed’ like any other.

Irredeemable?

Some Christians carry an assumption like this:

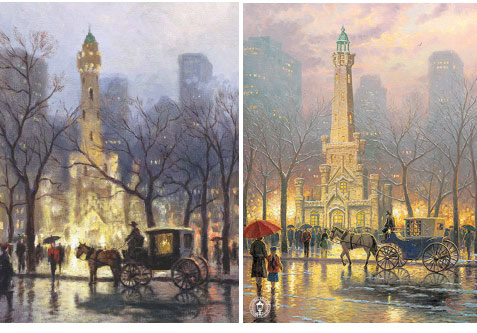

We can “redeem” secular, popular stories such as “Game of Thrones” or The Wolf of Wall Street. But silly devotionals and Thomas Kinkade artworks are beyond redemption.

Frankly, this assumption can betray our own immaturity.

Imagine someone who can’t stand the sight of his own child’s fingerpaint drawings,5 but reacts with praise at other children’s work.

If we believe God’s redemption of humans will (in some way, according to his word) lead to present and future redemption of culture, why leave out “Christian” stories and songs?

Someone may say, “But the Christian Fiction Industry is too far gone into Amish lit and so on.” But this is shortsighted. It seems to presume The Industry was founded by wizened bishops in the year 1635. Rather, The Industry has only existed a few decades. Among Christian institutions, this is likely one of the easiest entities to help change and improve.

4. Scripture expects Christians to have their own cultures.

The Bible’s existence alone quietly declares: Study this book. Read it, memorize it, quote the verses, understand these references, adopt this vocabulary, draw the pictures, write the songs. Create cultures that include this Book. Let it seep into and revolutionize your existing cultures.

Jesus and the apostles clearly established a “Church” means of spreading Kingdom cultures driven by Scripture and its Gospel. The capital-C Church is made up of little churches. Little churches are made up of people from many existing cultures, all put together in one group.

There is no way to pursue this divine mission without also getting subcultures with it.

5. ‘Christian fantasy’ can explore worlds ‘regular’ fantasy cannot.

Sure, thanks for that, magician-lady. Also: Who lit all your candles?!

Yesterday I saw a fantastic post by Scott Derrickson. He’s director of the upcoming Marvel film Doctor Strange. He’s also a professing Christian, and his social shares are full of depth.

Derrickson isn’t making “Christian movies.” He’s a light in broader culture. We need this!

But yesterday I also saw an episode of “Arrow.” A magician teaches Oliver Queen to resist dark spells cast by villain Damien Darhk. She tells Oliver: Use the light to resist the darkness. If you don’t have more light in you than darkness, you’ll only fuel the darkness. Helpful, right?

Secular stories have some freedoms. But they also have very tight limits. That’s one reason we need specifically labeled “Christian fantasy”: to explore deeper concepts than shallow and hackneyed “light defeats darkness” themes. Only a Christian making this story can deepen the magic system. Only we can say: The “light” is Jesus and his mission. Only in our “own stories” can we name Names and get specific, and go places other stories simply can’t.

6. Christian authors created many fantasy genres; it’s a family legacy.

Finally (for now), there’s no reason for Christians to shirk from attaching the famous family name, “Christ,” to the family business. We basically invented fantastical stories.

- Fantasy proper was born from medieval myths, leading to Lewis, Tolkien, et. al.

- Science fiction has its roots in unavoidably Christian categories for the world.

- Supernatural/horror is intrinsically linked to the most supernaturally true faith.

Should Christians enjoy (and create stories) that are outside “Christian” cultures? Yes.

Should Christians enjoy and create stories inside our Christian subcultures? Also yes.

We have no reason to avoid either sphere of influence. We have every reason to share a biblical vision of specifically God-glorifying creativity in every square inch of creation.

- I am using “fantasy” as shorthand for any kind of fantastical story, such as science fiction, supernatural, and fantasy proper. ↩

- Some refer to this as moving from the “CBA,” the Christian Booksellers Association, to the “ABA,” the American Booksellers Association. I won’t use these names here because I think they count as mild “jargon.” The names over-limit the broader issue by making it all about aspiring authors. ↩

- A lot of humans also have specific “industries” for their subcultures. This fact is not unique to Christians. What does seem unique to Christians is a silly sense of shame over this fact. ↩

- 1 Peter 3:9. ↩

- Or worse, imagine someone who privately blushes in embarrassment or even self-loathing at the thought of his own artworks as a child. ↩

Well said. As the persecution increases books are needed to help with the final harvest and strengthen God’s people. Thankfully, that is happening. Speculative fiction is one of strong tools in this effort.

In this day of the Great Falling Away, we need wonderful books which can transform lives. Some very good stories are being published these days. We break them up into five levels:

1: Clean reads: Vaguely Christian books with a positive world view.

2: Biblical or Old Testament stories: some sort of ancient writing from God. No savior.

3: Religious: Christian books with the emphasis on the church

4: Redemptive: Books showing transformed lives as a result of choosing to serve a savior/messiah

5: Spirit-filled: Stories where characters have a close, personal walk with God, talking to Him, hearing from Him, and seeing acts of power from His Holy Spirit.

The rating system can be seen in this free booklet. https://indd.adobe.com/view/e203b945-13d7-4941-9637-2664ee790bb1

More and more we see authors serving God by writing exceptional stories of realistic characters who’s lives are transformed by God. When’s the last time you read a book where your response to it was, “Praise the Lord. Alleluia!” Happened to me last weekend with a wonderful piece of science fiction by Yvonne Anderson.

For me, it’s kinda like saying “Why do we need ideas?”

But I think Christians forget that, too, that ideas from outside the Christian subculture are not automatically contamination. There are a lot of people invested in the false dichotomy of purity vs contamination, Christian vs mainstream. The perceived safety of Christian fiction, Christian bookstores, Christian schools, Christian nations. The allure of the Christian-underdog narrative when in reality American society is most often unfair in Christians’ favor.

Ideas don’t grow strong just from the suppression of other ideas. They need to have support of themselves, or they won’t last outside the greenhouse.

“ideas from outside the Christian subculture are not automatically contamination”

Absolutely! There’s a lot of truth in non-Christian fiction. I’m working my way through the first two seasons of Stargate SG1 just now, and there’s a lot of wisdom in there – and silliness too 🙂

“The perceived safety of Christian fiction”

And a lot of dangerous lies in Christian fiction (I’m thinking specifically of the ‘learn the moral lesson/become a christian and you will be materially rewarded/all your problems will disappear that is so prevalent in kids’ books. Grrrr)

Great piece. Only caveat I have is that Arrow is not as much a broad thing as it sounds. Ollie needs to choose light and not dark, hope and not despair. If seen in one eppy, it doubtless sounds like faux-philosophical crap. If viewed in the journey of the entire 8 years portrayed so far (4 present, 4 flashback), and knowing how he becomes Green Arrow, it makes more sense.

Still you are right, showing Jesus to be the way is something Christian fantasy can uniquely do. Whether by very overt references, somewhat more roundabout ones like Lewis, or more subtle but still clear ones like Tolkien.

Bravo. The only thing I want to add — wait for it, wait for it, waaaaiiiitttt forrrrrr ittttt — you left out another genre if not invented by Christians per se, was certainly initially fueled by their worldview — …THAT… i.e., horror, and I don’t mean supernatural thrillers, spiritual warfare novels, or modern urban fantasy in horror “dress.” I mean, well, um, ah, er, horror. The forbidden genre in the Christian subculture, As in Mary Shelley and Bram Stoker, the mother and father of the genre. Both wrote from a very biblical worldview and call us to God’s truth and power. It’s not my call to say if they were believers or not, but their stories definitely belong to this heritage. Horror deserves its place in your list too.

That is such a good point that I’m about to edit the piece to add that term to my mention of “supernatural.” Some time ago the SpecFaith team had a discussion about how best to break down the fantastical genres. The three categories we have ended up using are broad: fantasy, science fiction, and supernatural/horror.

While I agree with much of this, I would argue against claiming Mary Shelley wrote from a biblical worldview. In fact, the apologetics class that my wife teaches uses Frankenstein as a clear example of the humanistic view of man – that he is innately innocent and only society makes him sinful. Contrast this with The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyl and Mr. Hyde, which does operate from the biblical worldview that man IS innately sinful.

Whether or not the Monster is innately evil or becomes so because of what people do to him is a valid point for discussion, and one I believe Shelley left to the reader to decide. But I was thinking of the overall theme, which to me is best illustrated by the scene where Shelley opens with a gorgeous and detailed description of Vienna in spring bloom, Flowers and trees bud, birds sing, people head outside to revel in the parks and the sunlight. But not Victor Frankenstein, who huddles over his “work” in his lab with the curtains drawn, obsessed with the darkness that ultimately will claim both him and everyone he loves. This is the path he has chosen. It seems right to him, but its end is the way of death. The opposite of what’s going on outside, God’s natural creation as opposed to the abomination he is about to bring forth. The most powerful thing in the book, to me. Very, very biblical.

Excellent article, Stephen. Very clear and to the point. Nothing to add.

Becky

This is an great argument and makes me reconsider my own thoughts on the matter a little. I’ve always been of the mind that Christians hide too much from the true calling and tend to self-segregate for comfort. But there’s a valid point to be made for culture (though it’s more of a Western bent). The thing I think every author needs to consider is, who are you going to give your gift to? Is it for the Church or the World. I am convicted in a certain way but we all are called differently.

My main beef would be with the notion of limits. I find, as a woman who’s written for both the secular and the Church, the limits tend to be heavier on the Church side. The World has a much better time accepting theology and theories on Spirit than the Western Church—the former would blanch at many of the themes in my novels (in fact they have). Maybe we can work on that. But one of the reasons I began pitching my work in the ABA rather than the CBA was that freedom, as much as the desire to reach the lost. I have had far more criticism from believers than I have from typical readers (even though I have had my fair share of criticism for including a True God in my work).

I went through a sort of realization for myself. It was a personal choice, based on the fact that I felt like the Church didn’t want my brand of fiction. But I do agree that it’s important that the body has it’s own culture. I’d just add that we may not always have the most healthy view of what that should look like. In today’s world/market of CBA “Lord of the Rings” and Narnia would most likely be looked at sideways if presented. The only reason we laud such work today in the Church is because of history and awareness of what sort of men the authors were. That’s only known in hindsight.

And a separate culture of Church-big-C is a new thing for the most part, I would say since the sexual revolution of the 60’s (where before it was wrapped into the Western label as a given). So it’s a work in progress—sometimes I wonder what it’s meant to look like, really. But I do believe you’re right, there is a purpose. We just need to examine what that purpose might truly be.

As for me, I’ve been burned by the Big-C, as an artist, but that doesn’t have to mean I’ve given up on her entirely. 😉

Loved this post! While I do think more Christians should venture outside the subculture and write stories for the general market and be a light there, I also believe there’s value and importance to having the specifically Christian market as well. 🙂

I love what you had to say about Christians embracing their culture!

As someone who writes Christian psychological – and often about homeschoolers – I can totally feel left out and people’s disinterest. Thank you for this!