Refuting ‘universalism’ Slanders Of C.S. Lewis, Part 3

Last night I was shown another one — a website whose evangelical authors, surely with the best of intentions, ripped not only multiple C.S. Lewis quotes, but his whole life, out of context.

If I met the person who wrote this material, I would try to be gracious. After all, Christ saved me from so much worse; I was not, as the site’s authors seem to have expected of Lewis, free from un-Godly thoughts and impulses before He saved me, and I’m certainly still working on them! Still, I’d challenge such Christians to survey the contents of this series’ parts one and two, attacking the notion that Lewis was a heretic and/or accepted universalism:

- Lewis clearly believed in Hell, and was not a universalist as some falsely accuse. Thus we must address his direct, written agreement that Hell is real, just and permanent.

- The character Emeth going to “heaven” in The Chronicles of Narnia: The Last Battle is at best unclear, given that Narnia is a supposal, not allegory, and the variety of themes and interpretations that can be drawn from the vaguer-in-a-story Emeth Element.

Real Christians read Scripture (or should read it!) with right hermeneutics, not basing a whole System of ideas upon obscure verses, but instead seeking to let clearer passages interpret unclear ones, with heed to the original culture in which a book/text was written. Similarly, those who accuse Lewis of being a universalist need to survey his whole life and direction, and not let certain story tenets (which could “go” one way or the other!) not define his clearer statements.

Not universalist; still slightly fuzzy

That alone could refute C.S.-Lewis-was-a-universalist. Still let’s be fair: from what I have found, apparently Lewis did believe that God might provide some way to reach “good” people who actually did desire to know the true God. This seems close to the modern term anonymous Christians — that is, that some people may be covered by Christ’s grace without having directly embraced Him. Such was Kevin DeYoung’s reminder last month, after quoting Lewis:

There are people who do not accept the full Christian doctrine about Christ but who are so strongly attracted by Him that they are His in a much deeper sense than they themselves understand. There are people in other religions who are being led by God’s secret influence to concentrate on those parts of their religion which are in agreement with Christianity, and who thus belong to Christ without knowing it. For example, a Buddhist of good will may be led to concentrate more and more on the Buddhist teaching about mercy and to leave in the background (though he might still say he believed) the Buddhist teaching on certain other points. [from Mere Christianity]

No matter how much we may like Lewis, this is simply a profound misunderstanding of the Spirit’s mission (and a rejection of John 14:6). The work of the Holy Spirit is to bring glory to Christ by taking what is his–his teaching, the truth about his death and resurrection–and making it known. The Spirit does not work indiscriminately without the revelation of Christ in view.

Whether or not Lewis later revised his view, it is impossible to resolve it with Scripture. But is it heresy? After all, many Christians have similar-sounding beliefs about people born with mental issues, or children who’ve died in infancy. And as a scholar in such a secular realm, with even more anti-Biblical ideas about, should Lewis be faulted too much for buying into one early on?

In 2008 during a discussion on this, a friend of mine, Phillip Pugh, summarized Lewis like this:

One has to remember when reading Lewis that he is at heart a Medievalist even if his theology is basically Anglican. When reading Medieval works like Dante’s Divine Comedy (which had a profound effect on Lewis) we find that the “Noble pagans” like Socrates, Plato, and Virgil, are placed in a sort of limbo where they are not suffering and yet there is no light. I think Lewis has something of this in mind, taking some cues from George MacDonald to embellish it (though not taking it to MacDonald’s universalist extreme).

He is saying that Emeth had Tash and Aslan confused because of his cultural background. I disagree, but it’s not as bad as many would think.

I also disagree, but reiterate this: it’s not as bad as many would think. True Christians may believe wacky and/or un-Biblical things, such as: the King James Version (which one?) is God’s inspired Word even more than the manuscripts from which it was translated; the sun orbits the Earth; Madalyn Murray O’Hair and the FCC tried to ban Christian television in 1996 (sadly, they did not succeed); or Christians who read Harry Potter open themselves to demons.

More specifically about salvation, true Christians who understand that Jesus, God’s Son, died for their sins, may also believe that if you don’t speak in tongues, you don’t have the Holy Spirit. They may, out of ignorance, disbelieve in the Trinity — a crucial doctrine for understanding how God works. They may be even fuzzy about the doctrine that Christ was born of a virgin.

But does that automatically rule out their salvation status?

Aiming for essential Christian beliefs

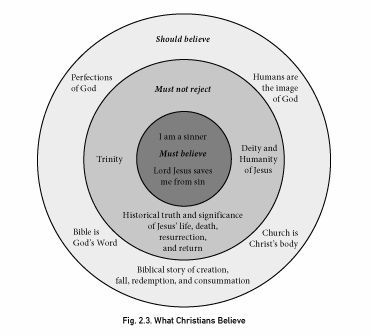

Author and professor Mike Wittmer suggests no. Why? There’s an ignorance clause. Christians may not know some crucial Biblical truths, but they must not willfully reject them. His beliefs-target diagram has gotten about the internet: showing, in the center, truths that Christians must believe to be saved; in the middle, truths that Christians must not reject if they hear and understand them; and in the outside, truths that Christians should believe and study.

Author and professor Mike Wittmer suggests no. Why? There’s an ignorance clause. Christians may not know some crucial Biblical truths, but they must not willfully reject them. His beliefs-target diagram has gotten about the internet: showing, in the center, truths that Christians must believe to be saved; in the middle, truths that Christians must not reject if they hear and understand them; and in the outside, truths that Christians should believe and study.

In the book of Acts, the bare minimum that a person must know and believe to be saved was that he was a sinner and that Jesus saved him from his sin. As Paul told the Philippian jailer, “Believe in the Lord Jesus and you will be saved” (Acts 16:29-31; cf. 10:43). This is enough to counter the postmodern innovator argument that we can be saved without knowing and believing in Jesus.

But any thinking convert will inquire further about this Jesus. While he may not know much more at the point of conversion than Jesus is the Lord who has saved him, he will quickly learn about Jesus’ life, death, resurrection, deity and humanity, and relation to the other two members of the Trinity. Anyone who rejects these core doctrines should fear for their soul.

According to the Athanasian Creed, whoever does not believe in the Trinity and the two natures of Jesus is damned. However, since it seems possible for a child to come to faith without knowing much about the Trinity or the hypostatic union (this is likely not the place where most parents begin), I take the Creed’s warning in a more benign way—that we do not need to know and believe in the Trinity and two natures of Christ to be saved, but that anyone who knowingly rejects them cannot be saved.

The final category is important doctrines which genuine Christians may unfortunately misconstrue. I think that every Christian should believe that Scripture is God’s Word, know its story of creation, fall, redemption, and consummation, and know something about the nature of God, what it means to be human, and what Jesus is doing through his church. However, many people have been genuine Christians without knowing or believing these things (though their ignorance or disbelief in these facts significantly diminished their Christian faith).

Thus, I believe that every doctrine in this diagram is crucially important for sound Christian faith. And some are so important that we cannot even be saved without them.

— from An Interview with Michael Wittmer, Between Two Worlds blog, Justin Taylor, Dec. 8, 2008 (boldface emphases added)

So — perhaps after checking that suggested diagram to ensure we’re in the faith! — I would put Lewis through these questions. For the center circle: Did he believe he was a sinner and that the Lord Jesus saved him from his sin? Most assuredly. From the outside circle: Did he accept the orthodox (though slightly less vital) beliefs about final redemption in a physical New Earth and the Church’s nature? Not all of it. He also smoked tobacco all his life (!), as the Lewis-criticizing website I mentioned above gravely notes. But that doesn’t make him a heretic.

The most interesting part comes in that center area of things Christians must not reject. Lewis was fuzzy about the Atonement, the nature of the Trinity, and — I would add this to it — the ultimate cause of Hell and sinners’ eternal punishment, and what “total depravity” means. He did not have access to the same resources that more-Biblical Christians may have today.

Therefore, I contend, Lewis was likely not directly exposed to those ideas and did not knowingly reject them for the reasons we hear from actual “heretics” today: humph, that’s not “my” God.

The same is true of a Oneness Pentecostal acquaintance I have, who I think simply hasn’t seen what the Trinity doctrine really states and defines. It’s true of Christians who are hooked on conspiracy theories about Satanism and C.S. Lewis, and for whatever reason refuse to let the God of truth sanctify how they practice truth-telling in those areas. And let’s admit it: this is also true of so many of the early Church fathers, whose beliefs excelled amidst the doctrinal conflicts of their days, defending the faith in those areas, even if they faltered in other fields.

Conclusion: Lewis, though sometimes confused, a Christian

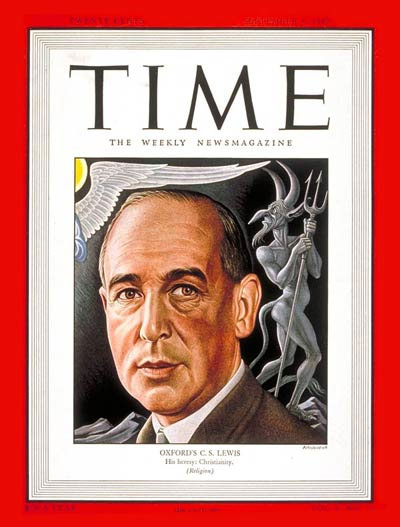

C.S. Lewis, though not a theologian and not a church father, is very similar to them: in the doctrinal areas under greatest assault in his society, he excelled. Rebutting unimaginative Christianity, he gave us The Chronicles of Narnia. Striking back against intellectual attacks on Christianity and anti-intellectual responses from other Christians, he gave us brilliant nonfiction.

He was not a universalist. He was not a closet compromising-with-Satan “pagan” either (that could be another series). From what we can tell, he believed the essentials of the faith: that he was a sinner and that Christ, by grace, saved him. That, at the core, makes one a Christian.

What does that mean for those who insist he was a heretic and/or a universalist? It means that if they’ve read this far, God bless ‘em, they’re now responsible for what they’ve read — just as Lewis would be, had he read and engaged a firm defense of Christ’s absolutely-exclusive claims and rejected them. Here I’ve attempted to show specifically that Lewis did not accept the false notion of universalism. The other attacks I may handle another time, such as the “pagan” thing.

But on this issue, if you go on from here and say again “Lewis was a heretic” or “Lewis believed in universalism,” etc., after already having been corrected and told how to verify it yourself — that is not Biblical discernment or even understandable ignorance. Instead, at best it’s willful ignorance; at worst, God-dishonoring slander of a fellow believer.

But on this issue, if you go on from here and say again “Lewis was a heretic” or “Lewis believed in universalism,” etc., after already having been corrected and told how to verify it yourself — that is not Biblical discernment or even understandable ignorance. Instead, at best it’s willful ignorance; at worst, God-dishonoring slander of a fellow believer.

Yes, I know that it can be tempting to push back against Lewis’ popularity, especially because of many evangelicals who may actually over-value his works, quote them nonstop, or use his views in defense of anti-Biblical ideas and practices. And yes, as a general rule, if someone or something is popular with The World, that’s a good signal for Christians to push back. But that alone is no reason to reject all of Lewis’ life and works. Christians should not live as if they must constantly Avoid Whatever is Popular in Culture, but instead live according to Christ. If culture happens to echo that, great; if culture doesn’t, we oppose that. But our goal is to be for the Biblical Christ who’s saved us, not merely Against All of The World. His popularity aside, Lewis was and remains a voice that glorifies God. Truth-minded Christians should thank Him for that.

An excellent series; thank you for the time and thought you’ve put into this. I especially like your closing remark that Christians should not live as if they must constantly Avoid Whatever is Popular in Culture, but instead live according to Christ. Well said.

Shucks, it’s always nice to be quoted.

I remember hearing a theology professor of mine say that if you are studying theology and haven’t had to wrestle with the questions of inclusivism and universalism, you will, because of the universal language used in the Bible to describe the effects of Christ’s sacrifice. Certainly if one reads the church fathers on the subject, there is a clear wrestling with this question. If we are to be faithful and Biblical theologians (which is what all Christians of sound mind should strive for) then we must wrestle with these questions and not judge those who disagree with us too harshly. We’re just as fallible as they, and if we’re right about anything, it’s by the grace of God, not because we’re smarter or more spiritual.

And frankly, Lewis himself admitted that he was only an amateur when it came to theology, and that if one had to choose between him and a classic author of Christian thought, one should go with the latter. I don’t think that there was anyone who disapproved of the cult of Lewis more than Lewis himself (one of the reasons why I admire him, actually). Lewis is not (like Calvin, Luther, Barth, or Athanasius) speaking with authority, and should not be taken as doing so.

Philip

I frankly don’t see what’s wrong with universalism period. I wrote a whole evangelical universalist sci-fi novel on the Macdonaldian model and I know I can’t get it published because it’s too liberal for the evangelicals and too conservative for the mainstream.

Still love your blog though guys.

John

Appreciate your support and readership, John! At the same time, it’s just impossible to make universalism square with (Lewis’s rationale) here, Scripture, the Church’s teaching through the ages, and plain reason. I don’t mind explaining more here about why I (and orthodox Christians) believe this way, but it sounds like you’ve already made up your mind on the issue. My guess is that’s a result of a different, salvage-style way of reading Scripture, taking a piece of it (such as “God is love”) away from the whole, and forming an internally consistent belief System whose tenets match each other, but not the Word.

This comment is not a reflexion on C.S. Lewis but the topic in general. There are numerous thoughts on the subject of universalism but the one that is most dangerous is what they call “Christian Universalism” (the epitome of an oxy-moron). There are those that believe exactly what the chart shows in fig 2.3 but yet believe in universalism.

There are two main thoughts.

1. Jesus died for the sins of all mankind. No matter what you believe or how you live you will have eternal life with God when it’s over here. You’ve been forgiven, you just don’t know it. (read Paul Young “The Shack” for a good example)

2. Jesus is your Lord and Savior. You truly believe your salvation is found in Christ but you only believe it to be true for you and not others. The Gospel is not for everyone so others can find a different path to the same God, as in Buddhism, Hinduism, Jehovah Witnesses, Mormonism or one of the thousands of other “paths”.

Are these people really saved by faith in Christ? I say no. The Jesus of the Bible is the ONLY way to be forgiven and the only way to eternal life. Those aren’t my words, they’re His. The circle chart above is good but it doesn’t come close to explaining enough. Is Lewis a universalist? I’ll have to ask him some day.

Steve — for that question, you might also consider Lewis’s words about Hell and its reality, and finality, in The Problem of Pain and also quoted in part 1. Also, I would sadly venture to say that someone who believes in universalism consciously and intentionally, without recognizing that it is through Christ alone and a conscious act of willful repentance and faith (thanks to the Spirit’s work), may not be headed for Heaven. Thus he will be unavailable to ask — only to be asked about.

I wasn’t saying that Lewis is a universalist. The joke was “I’ll have to ask him”. If I was able to ask him then obviously he isn’t a universalist.

However there are universalists that believe in Hell but it’s only for what they consider to be the worst of the worst… murderes, child molesters and such. The rest of the average sinners get a “get out of jail free card”.

Steve: And that illustrates why I should not offer responses to comments first thing in the morning, pre-coffee, and pre-re-reading to ensure I didn’t moronically miss a joke. 😉

LOL. I do the same thing. I also post comments while at at work, then get inturupted (how dare they) and completely loose my train of thought. I end up sounding like an idiot with no point to what I have to say.

Hello Stephen,

Just wondering where you got the “what Christian’s believe” target. I’m writing an article with the same concept and can’t find the original source.

-Eric Novak

Thanks, Eric. I quoted from (also from the end of the quote above) An Interview with Michael Wittmer at the Between Two Worlds blog, by Justin Taylor, Dec. 8, 2008.

Very interesting chart, quite helpful

I don’t deny that those whole-heartedly labeling Lewis as a Universalist are misunderstanding, but I also have to think there’s a level non-understanding of Universalism on your part. Theologically, it’s quite a bit wider and more conservatively centered than its literal definition might portray it as.

Teddy, the broad definition I went with is “Any belief that says all people eventually, somehow, are saved.” What’s your definition, then?

Also, I know many beliefs that are “conservatively centered” or seem that way — Mormonism, for example — but still aren’t based in Scripture. That’s my question about a belief, instead of “does it sound conservative enough?”. Moreover, my insistence on Biblical foundation isn’t out of some sense of obligation, but out of love for the God Who loves me.

I found some articles saying that it is possible that Lewis believed that universal salvation was possible “limited only by our own innate ability to deny God, even in death”, and that Lewis doesn’t completely reject Universalism but “provides explicit and detailed examples that together show salvation, while not being universal, is much broader, merciful and understanding than the church has often taught” (Nicholas Harelson, 2021).

This seems like a very reasonable take to me, but I haven’t researched Lewis and his beliefs extensively. What do you think?

The article I quoted:

https://northamanglican.com/the-salvation-theology-of-c-s-lewis/

Stephen hello. Thank you for your article refuting universalism. Universalism disagrees with the entire Bible. Please excuse me if I’m misunderstanding your view, but it seems that in your article you are assuming that C.S. Lewis was wrong about those never hearing the gospel still being provided some way to be saved. If I’m understanding your viewpoint correctly, I would like to point out that there is quite a bit of evidence in the book of Romans that Lewis was correct. The book of Romans has some passages in it which may give us a very clear description of the concept that Christ can still save people that have never read the New Testament to learn the specifics about Christ and His sacrifice on the cross. See below from Romans 10 how Paul describes that the faith that leads to salvation must come from hearing. He mentions a preacher which is one way to to hear, have faith, and be saved; but then it seems like he mentions those who have never heard from a preacher. Notice how he says that these people can still experience the hearing that can lead to faith and salvation:

[Romans 10:13-14, 17-18 NASB20] 13 for “EVERYONE WHO CALLS ON THE NAME OF THE LORD WILL BE SAVED.” 14 How then are they to call on Him in whom they have not believed? How are they to believe in Him whom they have not heard? And how are they to hear without a preacher? … 17 So faith comes from hearing, and hearing by the word of Christ. 18 But I say, surely they have never heard, have they? On the contrary: “THEIR VOICE HAS GONE OUT INTO ALL THE EARTH, AND THEIR WORDS TO THE ENDS OF THE WORLD.”

As you can see, they hear the voice that has gone out into all the earth, and to all the ends of the world. As you probably know, the capitalized letters in verse 18 above are a quote from the Old Testament which describes what that voice is which has gone out to all the earth. Here’s the quoted passage from the Psalms:

[Psalm 19:1-5 ESV] 1 To the choirmaster. A Psalm of David. The heavens declare the glory of God, and the sky above proclaims his handiwork. 2 Day to day pours out speech, and night to night reveals knowledge. 3 There is no speech, nor are there words, whose voice is not heard. 4 Their voice goes out through all the earth, and their words to the end of the world. In them he has set a tent for the sun, 5 which comes out like a bridegroom leaving his chamber, and, like a strong man, runs its course with joy.

So this voice which has gone out to the whole world is the witness of God’s/Jesus’s existence and creativity as it can be seen/heard through creation:

[Colossians 1:15-16 NASB20] 15 He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation: 16 for by Him all things were created, both in the heavens and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones, or dominions, or rulers, or authorities–all things have been created through Him and for Him.

If we delve deeper into Psalm 19, we find that the bridegroom in Psalm 19:5 above is Jesus, but also that several more references to Jesus appear in Psalm 19. If we put all this together, we could conclude that Paul, in Romans 10, is saying that Jesus even speaks to those who never read the New Testament through his voice which he pronounces through the beauty and majesty of creation. Further, we could conclude that this hearing of this voice of Jesus through creation, as Psalm 19 describes, can lead to faith which then leads to salvation. Paul seems to be answering the age-old question of what happens to those who never hear that Jesus died on the cross for them. If we look more broadly in the book of Romans as a whole, we find even more support for this throughout the book. For anyone who would like to look into this further to see all the supporting passages and details of what I have said, please see chapter 7 of my free online PDF book “Enslaved to Salvation” which can be downloaded from my website at https://go.davidaaronbeaty.com/salvation . I offer a free option to obtain the book because I believe that nobody should be prevented from learning about God just because they cannot afford to buy a book. I hope the book and my comments here can help people to understand that God places a high value on people and does not just discard them because they were not reached by a missionary. His voice has truly gone out to the ends of the world, and everyone has an opportunity for salvation unless they reject that voice. I would say that C.S. Lewis was just trying to describe something that Paul very overtly communicated to us in the book of Romans. God bless