C. S. Lewis Despised ‘Exmas’ Cards and Cosplays, But Loved Serious Celebration

Several of my friends sent us Christmas cards this season. I’m grateful for each of them.1 I’m also grateful people don’t automatically expect cards from me. Every year, House Burnett simply can’t spare the time. Still, I fight the sin of covetousness for those who do spare the time. I want to be grateful for those who have these gifts.

Plus, if you haven’t noticed, Christmas cards have gotten better. They’re less cheesy than they used to be.

Most of the time the card shows only photos of my friend’s smiling family members, paired with seasonal and Christlike wishes for the recipient’s merry Christmas. Sometimes the card includes a family letter. This update often includes rejoicings for blessings and laments for trials and sufferings in the previous year.

C. S. Lewis hated secular, sentimental ‘Exmas cards’

(Image from rawpixel.com / New York Public Library)

This role-model Christmas card marks a drastic improvement over saccharine, sentimental Christmas cards of yore.

Perhaps these were the sorts of cards C. S. Lewis clearly despised with all his being.

You won’t find anti-card rhapsodies in Lewis’s fantasy stories or apologetics books. Instead, you can find this scathing takedown in a Lewis collection called God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics, edited by Walter Hooper.

This holiday season, for maximum Yuletide cheer, go find Lewis’s satirical essay “Xmas and Christmas.” The short piece doesn’t feature much deep logic—only Lewis’s passionate conviction.

Lewis describes a strange land he calls Niatirb, whose residents “use the following customs”:

Lewis describes a strange land he calls Niatirb, whose residents “use the following customs”:

In the middle of winter when fogs and rains most abound they have a great festival which they call Exmas, and for fifty days they prepare for it in the fashion I shall describe.

First of all, every citizen is obliged to send to each of his friends and relations a square piece of hard paper stamped with a picture, which in their speech is called an Exmas-card. But the pictures represent birds sitting on branches, or trees with a dark green prickly leaf, or else men in such garments as the Niatirbians believe that their ancestors wore two hundred years ago riding in coaches such as their ancestors used, or houses with snow on their roofs.

And the Niatirbians are unwilling to say what these pictures have to do with the festival, guarding (as I suppose) some sacred mystery.

And because all men must send these cards the market-place is filled with the crowd of those buying them, so that there is great labour and weariness.

But having bought as many as they suppose to be sufficient, they return to their houses and find there the like cards which others have sent to them. And when they find cards from any to whom they also have sent cards, they throw them away and give thanks to the gods and this labour at least is over for another year. But when they find cards from any to whom they have not sent, then they beat their breasts and wail and utter curses against the sender; and, having sufficiently lamented their misfortune, they put on their boots again and go out into the cold and rain and buy a card for him also.

And let this account suffice about Exmas-cards.2

And they buy as gifts for one another such things as no man ever bought for himself.

—C. S. Lewis

Lewis: ‘For the sellers … put forth all kinds of trumpery’

Later on, Lewis conspires to share his gentle opinions about more Exmas traditions. He’s in full satire-Scrooge mode when he condemns:

- Gift-giving

And the sellers of gifts no less than the purchasers become pale and weary, because of the crowds and the fog, so that any man who came into a Niatirbian city at this season would think some great public calamity had fallen on Niatirb. This fifty days of preparation is called in their barbarian speech the Exmas Rush.

—C. S. Lewis

- Father Christmas cosplays

- The Exmas Rush

- Overeating

- Overdrinking

- Secular holiday traditions (versus sacred traditions)

Lewis concludes, “It is not likely that men, even being barbarians, should suffer so many and great things in honour of a god they do not believe in.”

Ouch.

Lest we call the good professor a literary legalist, recall that Lewis also shared many a friendlier take on Christmas. We need only recall the arrival of one Christmas-symbol into a stranger yet more sensible land. That land’s residents did not celebrate Exmas, but, for one hundred years, they also could not celebrate Christmas.

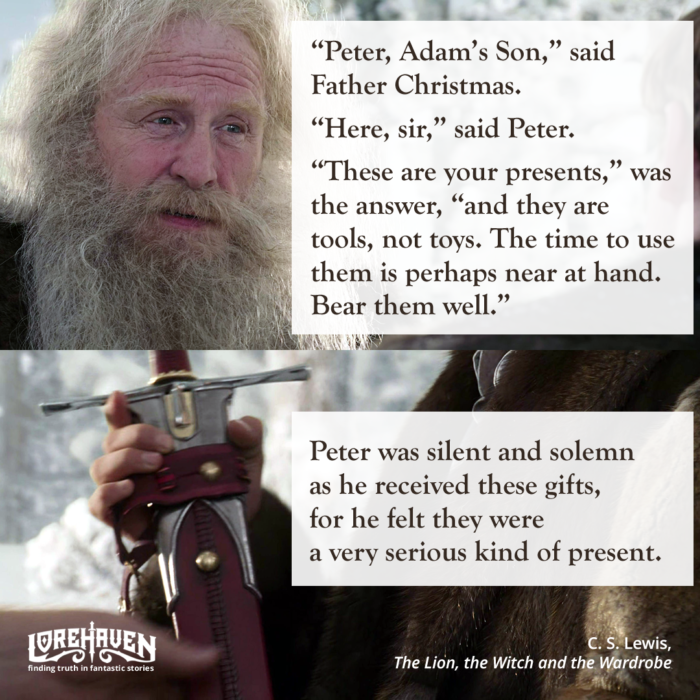

The true Father Christmas brings ‘a very serious kind of present’

In The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, the great Aslan’s power has finally begun to thaw the land of Narnia. Father Christmas is finally able to enter and perform his delightful duties. He serves Aslan, Narnia’s king. (In fact, if Aslan is a reflection of Christ, then Father Christmas is a reflection of Aslan.)

In The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, the great Aslan’s power has finally begun to thaw the land of Narnia. Father Christmas is finally able to enter and perform his delightful duties. He serves Aslan, Narnia’s king. (In fact, if Aslan is a reflection of Christ, then Father Christmas is a reflection of Aslan.)

Father Christmas is no mere Santa-cosplayer. He isn’t interested in Exmas or Exmas-cards. He cares not for materialism or gifts-by-obligation or excessive indulgence in any good thing. Instead, he joyously provides for the children’s and the Beaver couple’s immediate needs. He even gifts them a small feast, hearkening to future celebration of victory.

Best of all, Father Christmas grants each child a gift that is wonderful, yet also suited to each child’s abilities and real-world callings. When he describes Peter’s sword, he seriously reminds him, “These are tools, not toys. … Bear them well.”

Each gift comes with “conditions” on its use, especially given the Pevensies’ royal duties and the forthcoming battle.

Yet this is not deathly seriousness. Father Christmas gives serious, joyful life. To borrow Lewis’s later thought in The Last Battle, Father Christmas models “a kind of happiness and wonder that makes you serious,” which is “too good to waste on jokes.”

Here’s hoping we can attain that standard at Lorehaven, and expect this living seriousness—without wasted jokes or flippant indulgence—in the stories we love.

To all readers, especially those to whom I didn’t send an Exmas-card (i.e., all of you):

“A Merry Christmas! Long live the true King!”

- This article may mark the first(?) Lorehaven Christmas Special. We’ll resume Friday reviews after the holiday break. An original version of this article was published at SpecFaith on Dec. 24, 2019. I’ve also adapted material from this piece. ↩

- C. S. Lewis, “Exmas and Christmas,” reprinted in God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics, ed. Walter Hooper, pages 301–302. (I’ve added some paragraph breaks to the original text, just to help simplify screen reading.) ↩

Now I want a Christmas card saying, “Merry Christmas and long live the true king.”