Christians Who Feel Media Malaise Can Find Buried Treasure in Older Books

Not long ago in the movie theater, I added my sigh to the soundtrack.1 Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantamania had all the formula of Phase 3 Marvel with none of the heart. The movie played like a ruin, serving less to entertain me and more to help me grieve the dying cinematic universe I once loved.

Marvel isn’t the only world crumbling. DC, Star Wars, Doctor Who, even The Lord of the Rings—I just can’t get excited about any of it.

This ennui is all too common in the post-Endgame fantastical cinema landscape. While fans are left to tread water, some of us recognize this sudden dearth of good stories for what it is: postmodernism finally coming home to roost. When nothing is right or wrong, what good are heroes? And when characters are perfect from the start, only oppressed, why would they need conflicts to transform them?

Hollywood’s cinematic non-efforts and filler-heavy streaming shows hold diminishing interest for Christians already bored with the postmodern preaching in today’s stories.

Start digging for buried story treasures

For my girlfriend and I, one of the joys of our new relationship has been going through our favorite movies and filling each other in on what we’ve missed. She’d never seen Gladiator (2000), and I’d never seen Pride and Prejudice (2005), and we both recently found ourselves loving these new/old experiences.

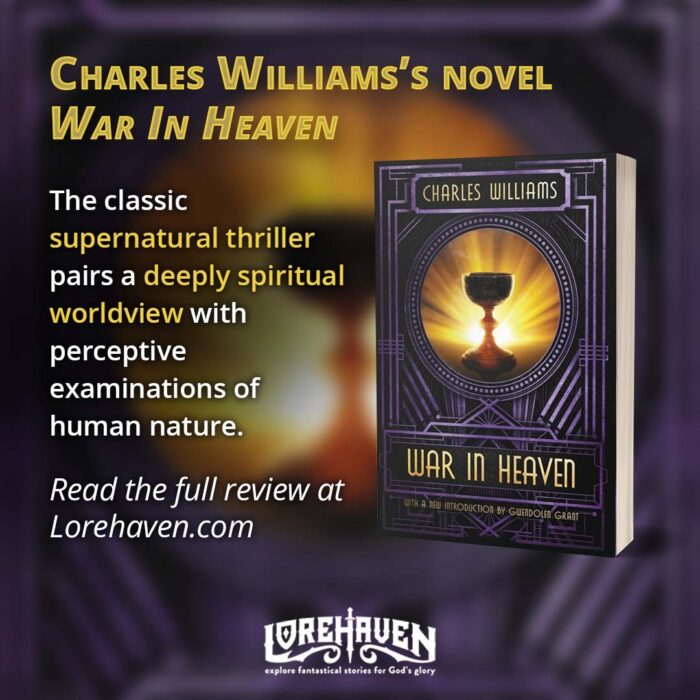

This brings me to Charles Williams’s 1930 spiritual thriller War in Heaven (read our review).2 On my way to see her, I finished the audiobook and adored it to the last word. Williams’ particularly British blend of creepy and commonplace, his joining of the wondrous to waking life, recalls my first experiences with two similar 20th-century works: G. K. Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday and C. S. Lewis’s That Hideous Strength.

This brings me to Charles Williams’s 1930 spiritual thriller War in Heaven (read our review).2 On my way to see her, I finished the audiobook and adored it to the last word. Williams’ particularly British blend of creepy and commonplace, his joining of the wondrous to waking life, recalls my first experiences with two similar 20th-century works: G. K. Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday and C. S. Lewis’s That Hideous Strength.

All three books soar miles above culture’s current film offerings. Yes, it’s hard to compare books to movies, but I can’t escape the quality parallels between these three novels and movies as young as Gladiator (2000), whose clipped, efficient dialogue is every bit as captivating as director Ridley Scott’s sumptuous production design. Pride and Prejudice is an even better comparison. As a direct adaptation, the 2005 Kiera Knightly film expertly preserves the book’s subtlety and confidence. It’s hard to imagine a version made today daring to even try dialogue this advanced.

But how do we best enjoy these older fantastical works? Facing such a mountain of stories, how do we find the gold? Let’s explore three tips for treasure-hunting:

1. Don’t expect works to align exactly with your theology

Thanks to online Christian discourse, we might feel more conscious about our theological differences. At our best, we can agree to disagree on the internet concerning secondary doctrines, and it’s important to apply the same understanding to Christian writers of the past.

Among the Inklings, Lewis famously held some theological views that still grate on most Christian minds. J. R. R. Tolkien was so fiercely Catholic that many Protestant readers might take issue with him. Williams, strangest of all, was a member of The Order of the Rosy Cross, a bizarre secret society said to practice magic.

Yet we can learn to look past these hangups to find thematically and theologically solid adventures (just as we might with secular writers). If we view War in Heaven through the otherworldly lens of imagination, we see a bold and exciting fight: Christians (Catholics and Protestants together) battling the forces of Satan. Just as we don’t believe in Hogwarts or Middle-earth, we don’t need to believe this is precisely how spiritual warfare works in order to enjoy the story’s deeper truths.

2. Be willing to push through cultural snags

Not many of us will expect older fiction to feature Disneyfied, mathematically diverse casts, beta males, or oppression-based conflict. These ideas simply weren’t the norm when many older works were produced. Creators tended to value historical accuracy over inclusion.

But we can slip into wanting to be spoon-fed smooth cultural experiences. A story’s setting doesn’t owe you an explanation. Just as a modern author can’t predict tomorrow’s cultural norms, authors of the past could not—and would not have cared to—predict what behaviors are acceptable today, except perhaps science fiction authors who actually wrote about their future.

Sometimes these differences can be downright offensive. Mark Twain’s famously casual use of the N-word is hard to read. But more often the new/old culture shocks will inform and transport us, and that’s when things get fun.

Imagine a version of Pride and Prejudice set in a 2023 American town. Why wouldn’t these girls just get jobs and make their own way? Why do they need to get married? What a slog this story would be. But in Georgian England? Suddenly we’re caught up in a world of etiquette and status games, with characters’ genuine feelings tested against the infernal gears of cold society. The setting becomes integral to the plot, and we’re transported. It’s much more fun to be shocked by the strangeness of antiquity than to expect stories to conform to our current world.

3. Apply the filter of time

We have so many books and movies to dig through. (Lest we suppose this is a new problem, rest assured that Back Then offered just as much shallow media as Now offers.) Every bookworm’s dread reality is that our lives won’t give us enough time to read everything we want to read. So how do we focus our time and find the gems amongst the common stones?

We have one advantage: time. As the ages pass, some books and movies leave the shelves, while others remain. Some works become instant classics, but others were considered shallow and commercial when they debuted, and only gained classic status much later (such as the novels of Charles Dickens and Edgar Rice Burroughs).

Just as erosion cuts through softer stone to reveal harder formations beneath, time reveals the best of the best. We can enjoy these works and go from there. Talk to friends. Read reviews. Join online fan groups focused on your favorite authors, eras, and genres. Check out your suggested titles in apps.

I like to read about my favorite classic authors to find out what authors they liked in their day. For example, Williams and Lewis met and became good friends after simultaneously reading each other’s books and sending each other fan mail.

Not all great authors get the recognition they deserve, and doubtless many have been buried in the stacks of history. In fact, finding the obscure work of genius can be a bigger thrill than experiencing the more famous titles.3

So many of our favorite franchises have withered under the zero-calorie diet of postmodern writing and the harsh labor of streaming renewal schemes. But that doesn’t mean we must swear off all fantastical stories. Seek the older works—books and movies—to rediscover what storytelling used to be and what it could be again.

- Photo by Kira auf der Heide on Unsplash. ↩

- In the Lorehaven Guild, we just finished our War in Heaven book quest for March 2023. You can join the Guild and still track the discussion for that book quest. ↩

- My favorite Hitchcock film? Foreign Correspondent. Look it up. ↩

Thank you, AD, for this article. Yes, I draw from the deep wells of classic literature as I write my futuristic science fiction. Were there ever the good old days of literature? I doubt it. But “zero-calorie diet of postmodern writing” is well put. Everything has gone flat. Or one could say, into the void has rushed fantastical creatures, gods, and demons, like in the most ancient times.

With older books you avoid a lot of the ubiquitous cinematic tropes–usually. There was less of a set formula back then for characters, so writers could afford to get away with doing things that are odd to modern sensibilities.

One older book I’d recommend is “The Cosmic Courtship” by Julian Hawthorne, son of that one Hawthorne you’re thinking of. It’s more fantastical science-fiction than romance, and despite some violence it has an innocent quality about it that you get from turn-of-the-century writing. And yes there is a overt Christian component, though it’s not constantly expressed, in some character motivations.

That sounds really awesome, Jay! I’ll put it in my TBR list!

Good article. I feel the same way. In recent years, I’ve been going back to the classics more and more. Jane Austen and Jules Verne in particular are just fun to read. I personally found your first point particularly challenging. When I read “The Inklings” by Humphrey Carpenter a while back, all I could think to myself was, “I could never be friends with Charles Williams!” But you’re right. In such cases, it can be helpful to put aside one’s theological beliefs to discover literary treasures.

As Christians, when we find Biblical truth in stories written by non-Christians, we rejoice. We use them in sermon illustrations. We make memes. But when someone claiming to be a Christian, but not seeming to be very good at it, writes a story containing Biblical truth, we shun it for its imperfections and drag the author’s character into it.

Williams’s real life secret society membership would certainly earn him a rebuke from Christians close to him, but within the fantastical context of his novel, we’re not meant to believe the details. Only the solid meta-truths. I believe this is the lens through which we should read all fantastical Christian fiction.