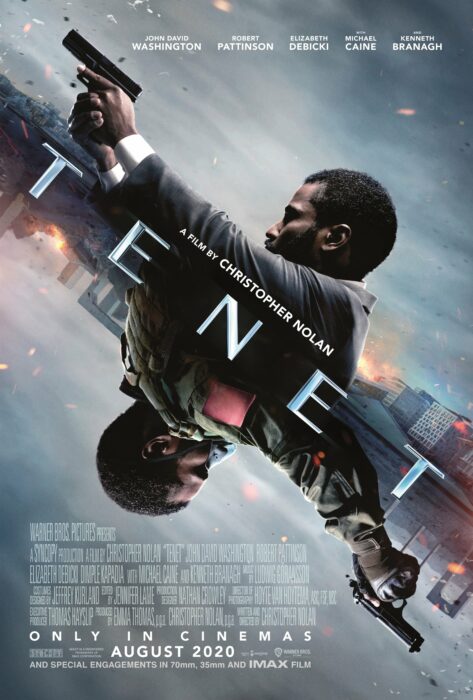

Christopher Nolan’s ‘Tenet’ Collides with Itself

To explore Christopher Nolan’s 2020 time-inverting spy thriller Tenet, we must recall that there are two types of time travel movies. These include movies in which time travel is a vehicle to advance the plot, and movies in which the plot is actually about time travel.

‘Wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey …’

The first type is far more common because time travel is a complex and difficult concept, with weird and potentially unknowable implications. It raises mind-bending questions like, “Is it possible to change your own past?” or, “If I met my future self, which one would be the ‘real’ me?”

Most time travel movies take a “less chat, more splat” approach. They just ignore such questions in order to focus on creating exciting scenarios. Is it ontologically possible for the Terminator to kill Sarah Connor? James Cameron doesn’t care. That’s because The Terminator‘s purpose of time travel is not to pose metaphysical riddles, but to set up the scenario of a woman being hunted by a killer robot.

About the second type, we find comparatively few movies in which time travel itself is the subject. These movies tend to be dense, obtuse, and obscure, like the 2004 indie film Primer. Many viewers of Primer come away shaking their heads, lamenting, “That didn’t make any sense.” And they’re right. With time travel, Primer tells us, you can never be sure why anything is happening. Cause can come after effect, so it is always possible that an event which happens today is a response to something that won’t happen until tomorrow. To the time-bound observer, this is effect without cause. It is impossible understand—impassible to trust—such a reality. Primer doesn’t make sense because time travel makes reality not make sense, and so it makes sense that Primer doesn’t make sense, which is the sense that it makes. (Whoa!)

Tenet: showing effects before cause?

This brings me to Christopher Nolan’s Tenet (2020).

Tenet is a strange movie, because it is unambiguously about time travel, but it is also a spy thriller.

Like Primer, Tenet is set in a world whose effects can precede cause. Events that happened yesterday can be caused by events that happen tomorrow, which can be caused by events which happen a month from now, which can be caused by events that happened last year.

Not only is this inherently confusing, but it also puts much of the plot off-screen. Because Tenet follows only the subjective timeline of its protagonist, it hides the causes of many events from the audience. Characters show up without any explanation about where they came from. People receive orders with no indication about who sent them. Climactic battle scenes don’t clarify who, exactly, the heroes are fighting.

That sort of thing is to be expected in a movie about time travel. But, in addition to being about time travel, Tenet is also about a charismatic secret agent saving the world and a beautiful woman from a Russian-accented megalomaniac with a superweapon, with all of the fights, chases, and dramatic confrontations endemic to the spy thriller genre.

This creates a contradiction: a movie about time travel will unavoidably be opaque and confusing, while a thriller must clearly communicate the shifting balance of power between opposed characters. How can the audience invest in onscreen conflict when the story’s time travel keeps the implications and consequences of that conflict vague or unknowable? It just doesn’t work.

In trying to be a thriller about time travel, Tenet sets itself an impossible task, and it fails. The two halves of its identity clash from the first scene to the last, and the result is a movie that is less than the sum of its parts.

Tenet still shows the quality of its parts

But while Tenet fails as a whole, each of its components is good in isolation. The film’s acting is excellent. Sets are beautiful. Action is tightly orchestrated. The soundtrack is thrilling, and Tenet’s peculiar method of time travel looks amazing onscreen. And while the protagonist pulls off exploits reminiscent of James Bond, he has none of Bond’s vices. He is a righteous hero who goes above and beyond the requirements of his missions to protect civilians, and who respects the women he works with. Nolan contrasts his noble character with the villain, whose extreme selfishness corrupts everything he touches. These characters are classic archetypes portrayed well, even though it’s seldom clear exactly what they are doing.

I came to Tenet with high expectations. I know that Christopher Nolan is capable of making great science fiction and great thrillers. Alas, Tenet is neither. It is, however, great spectacle, and it has a refreshing lack of morally troubling content. Viewers looking for well-developed concepts or coherent storytelling will be disappointed. But viewers looking for great visuals and some quality “wow” moments will likely enjoy it.

I found the fact that you only see the movie through the protagonist’s eyes a strength. Much of storytelling in movies is given an unfair omniscient view of everything. To say this was a movie that was supposed to be about time travel to me is also a misnomer. The nature of the time travel in the movie is much more realistic than traditional time travel tropes. One can only travel at the same rate going forward or backward, not jumping from 1985 to 1885 or 2015 for example. It is about time inversion of objects and people. Which is substantially different than traditional “time Travel” stories. I found their approach EXCEEDINGLY thought out and very well executed.