Mirror, Mirror, On the Wall: Did Snow White Consent After All?

If you haven’t already heard the commotion, Disneyland’s Snow White ride has stirred up “cancel culture” controversy and a flood of side-splitting memes. What’s everyone so upset about? Apparently when Prince Charming from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) kissed Snow White to wake her from her enchanted sleep, he did so without her consent. Some critics say that could encourage date rape.

I could probably write a short book detailing the many problems with such thinking.

Instead, let’s start with what critics have right: It’s essential that a woman give a man consent to touch or kiss her.

Can we all just agree that sexual assault is a prolific issue that shouldn’t be taken lightly—in a world where one in four girls, and one in two women is sexually assaulted during her lifetime? Thank you and amen.

Believe it or not, I won’t argue about whether the prince should have kissed Snow White without consent in this scenario. (Personally, if I were stuck in an enchanted sleep, I’d definitely go for the un-consented kiss rather than being stuck in a glass box until I rot.) But in this debate, it’s particularly odd that Disneyland’s critics have missed one key fact: Snow White did give the prince consent to kiss her.

Clear away the fog of chronological snobbery

If we look at dated films and books through a modern lens, we can become overly confused with ethical problems that aren’t actually there. When the story fails to fulfill our current cultural moral standards, we assume the story is immoral and cry for its “cancelation.” This feeds what C. S. Lewis coined “chronological snobbery,” the idea that past things are intrinsically inferior to present things.

In this film, our modern mirror clouds us from beholding the true nature of the relationship between Prince Charming and Snow White at the story’s beginning.

In Walt Disney’s Snow White film, the future lovers first meet when Snow White sings into a well. At first, she is startled by the prince’s sudden appearance, and she runs into the castle. After overcoming her shock and embarrassment over her tattered dress, Snow White walks onto the balcony. There she flutters her lashes as the prince serenades her from below. In the prince’s song, he proclaims that Snow White is his “one love.” Then a dove lands on her hand, and she pecks a kiss to its beak. That same dove then flies to the prince, and relays the kiss to him.

During that era of Disney, such brief, romantic interactions were sufficient not only to kiss, but to fall in love. If Snow White had not been under the thumb of her evil stepmother, she could have married the prince right then and there.

It’s these stereotypical moments of love-at-first-sight that future Disney films critique, such as when Frozen’s heroine Elsa tells her sister Anna that she couldn’t marry a man she’d just met. This was a fair criticism, and one that appropriately described modern sensibilities without cancelling the past.

In Disney’s fairy-tale film language, Snow White consented

The prince’s song proclaiming his love, and Snow White’s unspoken acceptance, is sufficient consent for his kiss at the end of the movie.

Why?

Because in 1937, people would have understood that this interaction implied the prince and Snow White were in love and in a relationship. At that time, it was common for movies to employ the same storytelling devices used in fairy tales—flat characters and quick plots. Storytellers used these to spin tales with morals, not to draw you into a deep knowledge of characters or worlds as we do today.

If you add the dove serving to relay Snow White’s kiss to Prince Charming, we see her giving him more than just consent, but a kiss of sorts. This sets the foundation for his consensual kiss at the movie’s end. We can safely refer to this kiss as consensual, because a man no longer needs to ask permission from his fiancée or girlfriend to kiss her every time. She grants him permission based on their existing romantic relationship—even if she happens to be asleep (enchanted or otherwise).

Respect a story’s intentions before you try to ‘cancel’ it

God desires his people to read Scripture while keeping the original author and audience in mind. That way, we can understand the true meaning of the text.

Errors of poor hermeneutics have led previous Christians to use Scripture for defending popular errors in their contemporary ages, such as slavery. This led to slavery’s growth in the west as well as defamations of the Bible and God himself.

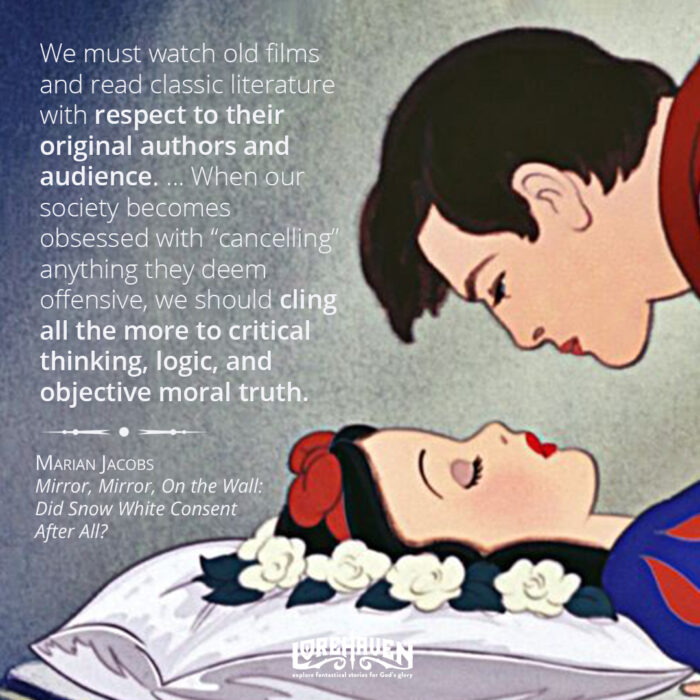

Similarly, we must watch old films and read classic literature with respect to their original authors and audience. To do this, we may need to do some extra research and critical thinking. Yet when our society becomes obsessed with “cancelling” anything they deem offensive, we should cling all the more to critical thinking, logic, and objective moral truth.

I think some people just want something to complain about. it’s a classic fairytale. You presented your argument very well.

This is a clear, sensible analysis of Snow White that applies to fairy tales in general. Originally, they were short spoken stories that made their points quickly, hence through symbols. “Love at first sight” did not mean they fell in love because of their looks; it was a convention that the listeners to these tales understood to mean that they’d found true love.

Terrific article! Thanks, Marian!

Debating over the morality of a kiss like that can be an interesting topic, and it’s good for people to have those discussions. Where the problem tends to start, especially now days, is where people pick out a character behavior that REALLY offends them, and then use it as an excuse to attack the story, author, or anyone that disagrees with them(rather than having an actual open minded argument and debate). There’s a difference between debating and the desire to force a story/trope/whatever out of existence just because it’s upsetting.

Some of it just comes down to what each person feels personally upset about. There’s a whole plotline about Snow White’s abusive mother trying to kill her, but apparently some would rather hone in on the prince(even though he saved her) because consent, as a social issue, offends them more. I’m not at all saying that to dismiss what rape victims go through. It’s a very horrible thing and something people deserve to be upset about, but it’s still important to acknowledge why people react to things a certain way.

If people don’t like what a character does, they can express that opinion and the reasons for it, but should be willing to truly consider arguments to the contrary. And instead of seeing offensive character behavior as an excuse to attack a story or author, they should use it to discuss the issue at hand. Then people can learn positive lessons from stories, rather than negative ones. That’ll help fans have a better experience with the tales they read and the fandoms they participate in, since they won’t be as afraid of getting canceled for disagreeing with the wrong people at the wrong time.

Also, as an example of a real life issue that can offer a bit of perspective… I took a first aid class years ago, and they defined what to do if someone has a medical emergency, but is unable to ask for help because they’re unconscious or whatever. The instructor basically said the rule was that, if you’re ABLE to communicate with that person, you tell them that you know first aid and ask if they want your help. But if they’re UNABLE to communicate, you’re supposed to assume they want your help.

Ok, just realized I should clarify the last part. To compare the paragraph about first aid to the situation in Disney’s Snow White, I’m saying that it’s a situation where the prince should probably assume she wanted him to help her wake from the witch’s curse. BUT, I am in no way, shape or form saying that someone should assume an unconscious person is giving consent for sex/kissing/etc.

Autumn, I mostly agree except for the comparison of consent versus child abuse. These really aren’t the same at all since the villain is doing one (implies child abuse is evil) and the hero is doing the other (implies non-consenting kissing is good). Of course, I don’t think this stories falls into that category at all so it’s a moot point (cow’s opinion IMO). But if I agreed with the cancel crowd on this issue, I would make that argument.

I like the CPR example.

It’s like the cancel mob doesn’t know magic is a thing in fairytales. They grew up like Eustace, always reading the wrong books.

A more recent controversy that annoys me just as much as the Snow White controversy, is about The Time Traveler’s Wife. In that sci-fi story, a man jumps back and forth through time against his will, out of his control, and at some point in his future he discovers that he’s married to a woman. He then gets time travel back to where he meets this woman as a young girl, knowing he’s going to one day marry her. This is all a very fun timey-wimey sort of fairy tale type of story, but in recent years the online “critical” narrative has emerged that this is actually a case of grooming, where an adult male convinces a young girl to fall in love with him. I mean, sure if this really happened in real life, it would probably come across as kind of icky, but the novel makes it clear that both sides of this romance kind of had no choice in the matter, and both kind of resisted it, but true love wins out in the end. But it just distresses me to see so much chatter about how problematic this story is. The author’s intent should trump everything else. As a reader we should be intelligent enough to understand what the language logic of the story is trying to tell us and go with it.