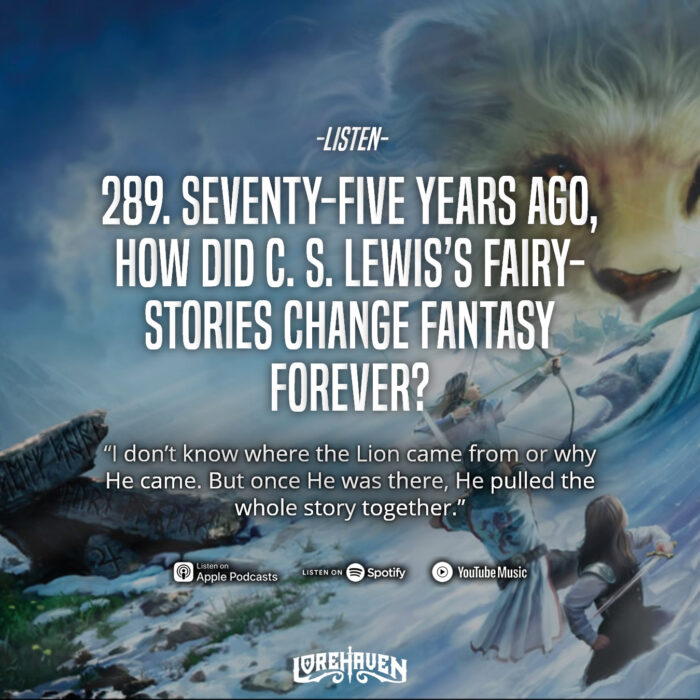

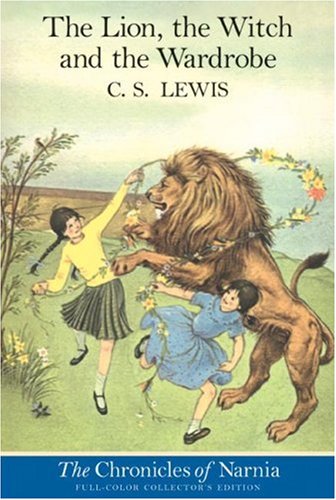

289. Seventy-Five Years Ago, How Did C. S. Lewis’s Fairy-Stories Change Fantasy Forever?

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 58:06 — 54.5MB) | Embed

“Suddenly Aslan came bounding into it.” That is how C. S. Lewis described the plot twist in his creative process for The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. “I don’t know where the Lion came from or why He came. But once He was there, He pulled the whole story together.” And in turn, this story has pulled together the imaginations of millions across the world. Now, 75 years after the first Chronicles of Narnia book was published, let’s explore how this changed fantasy forever.

Episode sponsors

- Sons of Day and Night by Mariposa Aristeo

- A Faie Tale by Vince Mancuso

- Above the Circle of Earth by E. Stephen Burnett

Mission update

- New at Lorehaven: our retro review of Kathy Tyers’ Firebird

- The Sun Eater Series is the Modern Sci-Fi Epic Christians Have Been Awaiting, article by Josiah DeGraaf

- Subscribe free to get updates and join the Lorehaven Guild

Quotes and notes: exploring Narnia

Quotes and notes: exploring Narnia

- The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe review at Lorehaven

- The Chronicles of Narnia series review at Lorehaven, March 2020

- Fantastical Truth episode 24. How Do We Defeat the Top Seven Myths about The Chronicles of Narnia? Part 1

- Episode 26. How Do We Defeat the Top Seven Myths about The Chronicles of Narnia? Part 2

- Episode 35. Did C. S. Lewis Say It’s ‘Pure Moonshine’ to Create Stories that Teach Christian Truth?

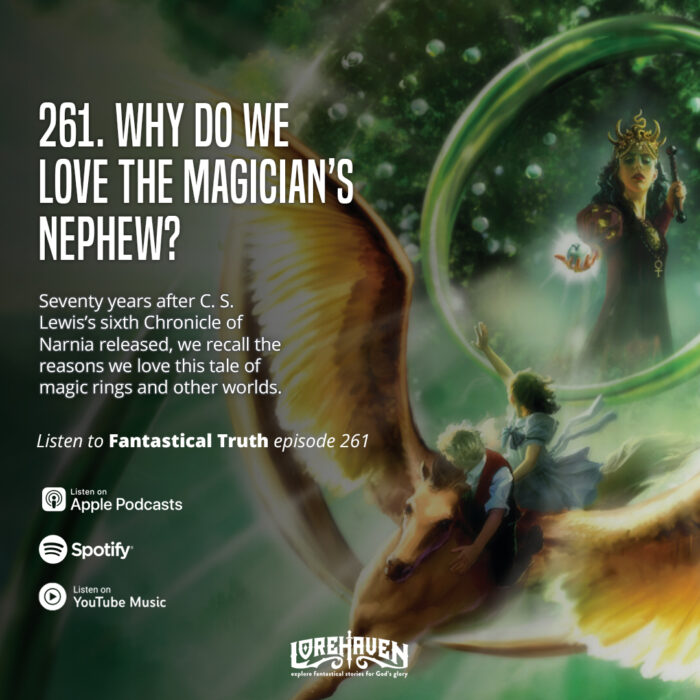

- Episode 261. Why Do We Love The Magician’s Nephew?

Quotes and notes: the creation of Narnia

Some people seem to think that I began by asking myself how I could say something about Christianity to children; then fixed on the fairy tale as an instrument; then collected information about child-psychology and decided what age-group I’d write for; drew up a list of basic Christian truths and hammered out ‘allegories’ to embody them. This is all pure moonshine. I couldn’t write in that way at all. Everything began with images; a faun carrying an umbrella, a queen on a sledge, a magnificent lion. At first there wasn’t even anything Christian about them; that element pushed itself in of its own accord.

—C. S. Lewis, “Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s To Be Said,” (1956)

All my seven Narnian books, and my three science-fiction books, began with seeing pictures in my head. At first they were not a story, just pictures. The Lion all began with a picture of a Faun carrying an umbrella and parcels in a snowy wood. This picture had been in my mind since I was about sixteen. Then one day, when I was about forty, I said to myself: ‘Let’s try to make a story about it.’

At first I had very little idea how the story would go. But then suddenly Aslan came bounding into it. I think I had been having a good many dreams of lions about that time. Apart from that, I don’t know where the Lion came from or why He came. But once He was there He pulled the whole story together, and soon He pulled the six other Narnian stories in after Him.

So you see that, in a sense, I know very little about how this story was born. That is, I don’t know where the pictures came from. And I don’t believe anyone knows exactly how he ‘makes things up’. Making up is a very mysterious thing. When you ‘have an idea’ could you tell anyone exactly how you thought of it?

—C. S. Lewis, “It All Began with a Picture,” 1960

[Narnia’]s beauties often get blunted or made lukewarm by the persistent myth spread by well-meaning readers, including many Christians, that the Narnia books are merely “allegorical.” (For example, one author even wrote that Professor Kirke’s mansion “is symbolic of the church” while the wardrobe “symbolizes the Bible.”)

But the “allegory” label ignores the stories’ true purpose according to Lewis, who insisted on calling his world a supposal. In one letter, Lewis wrote that his Narnia stories answered the question, “What might Christ become like if there really were a world like Narnia and He chose to be incarnate and die and rise again in that world as He actually has done in ours?” Lewis then concluded, “This is not allegory at all.”

Case closed. And Aslan be praised that it is closed, because if we turn these stories into mere allegory, we might end up using Narnia like a mere code or container pointing to “higher” ideals.

—The Chronicles of Narnia series review, Lorehaven, March 2020

1. The Lion …

- Lewis took great care to model Aslan’s behavior on our true Lion.

- When the kids hear of him, they have deep heartfelt responses.

- (That’s why this is book 1, because Aslan must be a surprise to us.)

- We love this hero because he’s “not a tame Lion, but he is good.”

- And in this story, Aslan directly repeats the death and resurrection.

- Lewis in another famous essay disclaims a popular Christian idea.

- It goes like, “To make fantasy ‘Christian,’ it must be allegory.”

- But the series isn’t allegory, and Lewis found deep meaning later.

- Nor is Aslan a simple allegory for Jesus; in this world, Aslan is

- In modern terms, imagine if Jesus were active in a “multiverse.”

- Yes, it’s still imaginary. This idea wouldn’t work in serious theology.

- That’s the beauty of fantasy; this needs no “allegory” for support.

2. … The Witch …

- Somehow the White Witch has become nearly as famous as Aslan.

- There’s of course the Snow Queen inspiration that ties her to myth.

- Yet oddly, Lewis also references the myth of “Adam’s first wife.”

- Beaver states this as fact, but we later learn her true origin.

- Here, however, it’s enough to see her as the iconic evil ice queen.

- Jadis is an overt inversion of the “nurturing” mother-figure.

- In modern terms she may seem shallow—no motive, no backstory.

- But as Lewis has said, the fairy tale’s beauty is partly in its brevity.

- The White Witch is a Satanic-level foe who corrupts the seasons.

- Lewis, at heart a medievalist, likely built Jovian motifs in the story.

- That is, a kingly and joyous victory over forces of cold and death.

- Remember, unlike the film, it is Aslan who wins, not the Pevensies.

- (Yet major shoutouts go to Tilda Swinton for defining this villain!)

3. … and the Wardrobe

- When Stephen was a kid, he read the Narnia series all wrong.

- Those first four books’ “portal” moments felt most fascinating.

- g., the wardrobe, the train station, the painting, the moor door.

- There is a genuine thrill to the idea of stepping into other worlds.

- Yet to this day, perhaps the Wardrobe is the best way into Narnia.

- Children then as now can hide in real closets and deeply imagine.

- If we grew up with Narnia, who hasn’t thought it could be true?

- This seems a great gift of God, to micro-“believe” these fantasies.

- Perhaps even Father Christmas, on some days, feels possibly real.

- And then, when the fantasy ends, you must re-face the real world.

- Lewis abruptly and almost tragically ends this story in England.

- Later books expand the world and the deeper meanings of Narnia.

Com station

Top question for listeners

- How did you first read The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe?

Next on Fantastical Truth

Long ago, before the great lion Aslan bounded onto bookshelves, C. S. Lewis wrote a science fiction novel set on mythological Mars. From there his hero Dr. Elwin Ransom was carried by angels to the sister planet Venus. And from there … the Ransom/Cosmic/Space Trilogy descended to the dull world of college board meetings, inner-ring politics, and a secret technocratic society bent on world domination with the aid of mad science and demons and everything. Eighty years after That Hideous Strength was published, we explore why C. S. Lewis created this earthbound and weird and wonderful pre-political supernatural thriller.

I found the Narnia series in my school library when I was in 4th grade, and yes, they were in the proper order. It was a watershed moment for me. I bought myself a boxed set a few years later. Boy, did I look for portals! 😄 When I get into a discussion about the book order, I point out The Magician’s Nephew is a prequel, explaining the back story of the first book.