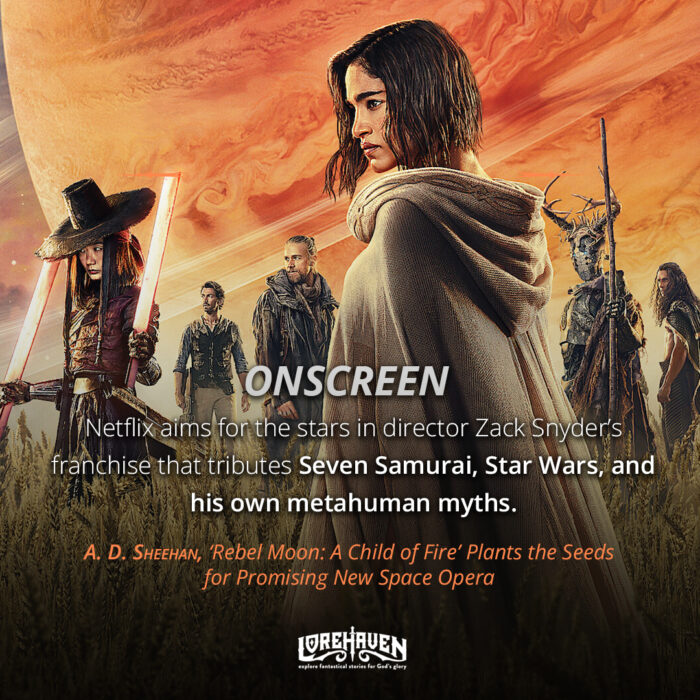

‘Rebel Moon: A Child of Fire’ Plants the Seeds for Promising New Space Opera

Last month, Zack Snyder’s distant-future sci-fi epic Rebel Moon Part One: A Child of Fire became a fan favorite. But critics rate it lower than Snyder’s previous films. Why this divergent response? How may the story’s format hurt our viewing experience? And what does this movie teach us about processing fantastical stories in general?

Rebel Moon starts a new gritty space-opera saga

The film centers on Kora, an elite Imperium soldier who deserted in disgrace and fled to a small farming town on a remote moon. When Imperium soldiers arrive to hunt rebels, they demand the town’s food stores and install a garrison to supervise the work. Predictably, things get violent. Kora defends the life of a village girl from rapacious soldiers. Now she must strike out across the galaxy, searching for warriors to help defend the townsfolk against the returning Imperium forces.

That’s the summary, and on first glance it may seem little but a rehash of familiar genre plotlines. But Rebel Moon’s part one has many more foundations in movie history. So take your seats. It’s time for Film History with Andy.

Every movie exists on a spectrum between formalism and realism. Whole books have been written on the theory. But to simplify, Saving Private Ryan is an extremely realistic movie, while 2001: A Space Odyssey would be extremely formalistic. Realism conveys grounded continuity to real life, while formalism focuses more on the medium as it conveys platonic forms of concepts.

To use two examples from the early Marvel Cinematic Universe, Iron Man is more realistic and Thor is more formalistic. Tony Stark uses reality-based technology to create his suit, while Thor features the titular hero riding a horse on a rainbow bridge between a tiny, flat planet and the gate to the Bifrost. In Iron Man, you’re supposed to think about how the suit works. In Thor, you’re supposed to sit back and react to the concepts. Both are valid ways to tell a story.

How to enjoy Rebel Moon by asking better questions

The problem is that most modern Western cinema is more realistic in nature, to the point where we no longer know how to process formalist cinema. That’s why we ask questions of Rebel Moon as if it were cousin to Saving Private Ryan, e.g., how could Kora actually win against the Imperium with so few warriors? Are they really still driving plows with horses? Why is that guy using a spear when he could use a gun?

The right questions for a formalist movie are more abstract:

- Why does a robot have more honor than most humans?

- At what point do you stop running from your trauma so you can pick up your weapon and fight injustice?

- What becomes of an omnipotent civilization after the death of its virtues?

Snyder’s entire career has been about myth: the bird’s-eye view of metahuman archetypes smashing into each other at the speed of light. In 300 (2007), a tidally advancing empire meets the rocks of an elite defense force. In Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016), Superman’s godlike power meets Batman’s obsessive vengeance. And in Rebel Moon, the vast Imperium meets the unkillable warrior it had forged, ruined, and discarded. It’s all perfect for the realm of formalism.

This is why fans of fantastical fiction tend to resonate with Snyder’s movies, while the average viewer will not. Formalistic myth has been woven into us since we first read of the chaining of Melkor in J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Silmarillion.

Moreover, the film’s deeper moral themes will resonate with Christian readers—the search for lost honor, a shot at redemption, and defense of the helpless. Biblical concepts abound, with strong moments of courageous self-sacrifice and an elevation of the lowly. Life is treasured, so much that it almost seems alien in today’s culture. These worldview themes are all classic hits for us, but wider postmodern audiences seem to find them baffling and sappy.

Rebel Moon does err on tribute and condense key moments

However, none of this excuses Rebel Moon’s faults. The action choreography often lacks energy, and no amount of formalistic musing can smother general continuity errors. There’s also no ignoring the fact that Rebel Moon is The Seven Samurai. It’s painfully close. Closer than The Magnificent Seven. Closer even than the anime Samurai 7. Maybe not as close as that one episode of The Mandalorian. But it’s just too derivative to even be called an homage.

Yet I can’t help but imagine that most of Rebel Moon’s issues are in the packaging. As of today, A Child of Fire is part one of a two-part movie. Apparently, if Netflix is keen, those films could be followed by a pair of trilogies.

Snyder first pitched the movie as a television series. What if Netflix had chosen that format? A Child of Fire would be season one, with Kora and company fetching a new member of the crew for each episode. This would give everyone time for backstory and motivation. It would go on from there until all of A Child of Fire’s history had consequence and the grand epic of Kora vs. the Imperium was told.

But instead of a longer-form series, a succinct movie, or a trilogy of three complete acts of a larger story, we got a long movie split jarringly in two, then likely padded with footage to swell runtime and give Netflix a big resubscription event. Rebel Moon’s many critics should look first to the office building, not the director’s chair.

We’ll have to wait until April to find out if Rebel Moon Part Two: The Scargiver delivers on A Child of Fire’s setup. With stunning visuals and creative worldbuilding, this universe deserves a far greater story than another Seven Samurai knockoff.

Definitely should have been a series. They story feels so compressed as if it’s missing scenes. I don’t think the planned extended edition will help. I’m surprised it wasn’t stronger coming from Snyder, and I thought he had been given more control. Sure doesn’t look that way.

This will contain spoilers, so stop reading here if you haven’t seen the movie.

I really wanted to like this movie, but I couldn’t suspend my disbelief enough to get past 2 scenes: The survival of the bad guy at the end of the movie (with intact teeth that were previously knocked out), and the escape and victory of the protagonists at their “all is lost” moment.