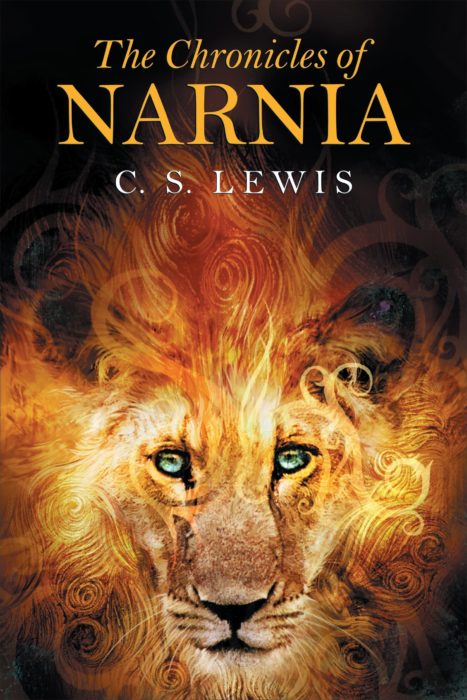

The Chronicles of Narnia

By Aslan’s mane, one cannot collect any sort of list for the best Christian-made fantastical fiction without including C. S. Lewis’s septet, The Chronicles of Narnia.

From the Oxford scholar’s first Narnia journey, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950) to The Last Battle (1956), all the seven chronicles have delighted and engaged millions of readers, far beyond the “children’s” label often ascribed to the series.

What if you only read one or more of the books as a child? Or what if you have only read the first book, and only followed Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy through that magic wardrobe into that winter-locked land in need of Christmas and then Aslan’s spring? If so, then by the Lion, you as an adult shall be blessed. Read the Chronicles today, all of them, and in publication order (yes, Narnians, we will die on this hill).

As Lewis once wrote of his friend J. R. R. Tolkien’s epic fantasy magnum opus, so the same endorsement could apply to each Narnian episode: “Here are beauties which pierce like swords or burn like cold iron. Here is a book which will break your heart.”

Alas, those beauties often get blunted or made lukewarm by the persistent myth spread by well-meaning readers, including many Christians, that the Narnia books are merely “allegorical.” (For example, one author even wrote that Professor Kirke’s mansion “is symbolic of the church” while the wardrobe “symbolizes the Bible.”)

But the “allegory” label ignores the stories’ true purpose according to Lewis, who insisted on calling his world a supposal. In one letter, Lewis wrote that his Narnia stories answered the question, “What might Christ become like if there really were a world like Narnia and He chose to be incarnate and die and rise again in that world as He actually has done in ours?” Lewis then concluded, “This is not allegory at all.”

Case closed. And Aslan be praised that it is closed, because if we turn these stories into mere allegory, we might end up using Narnia like a mere code or container pointing to “higher” ideals. Like the foolish Uncle Andrew, we might stand in the middle of a wondrous world being created by a Lion’s song, and think only of the stuff we can shove into the soil to dig up more of the machine parts that we want. Narnia’s beauties, however, are far greater than this. By humbling ourselves as little children, we are better placed to gaze up into Aslan’s not-tame eyes and golden mane. Then, by knowing Aslan there for a little, we might know Jesus better here.

Best for: Readers of all ages who love adventure, whimsy, and profound truth.

Discern: Strong magic, often based in Aslan’s power but often operating as a “natural law” of Narnia and the lands beyond, including magic by evil creatures; violence, including actions such as beheadings that are described in few words; some swear terms and even misuses of God’s title, yet hidden by British spellings.

[…] actually has done in ours?’ Lewis then concluded, ‘This is not allegory at all.'” See our review of The Chronicles of Narnia. […]