‘Tarzan Of The Apes’ Is A Dark, Misguided Adventure

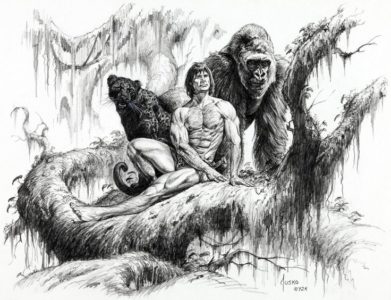

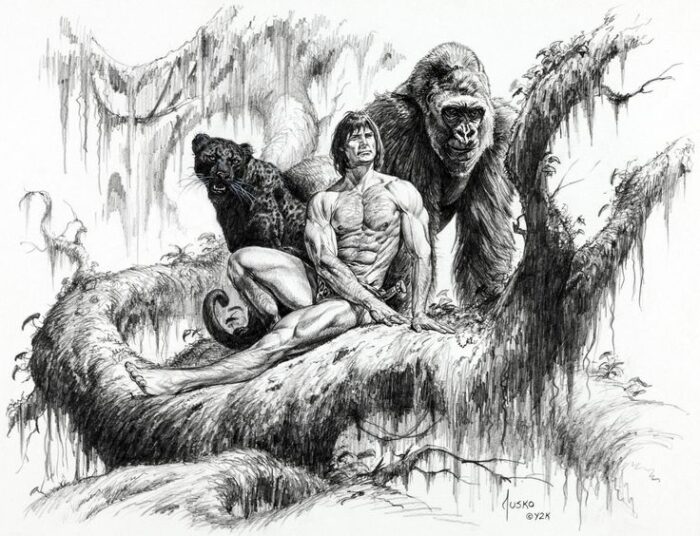

It is the rare but glorious lot of writers to create a cultural icon that lasts generations, one of those things that everybody just knows even if they’re not sure how. Tarzan is one such icon. Who doesn’t know the image of the handsome, wild, muscular man swinging through the jungle with the agility of an ape? Sometimes there’s a girl in his arm, but to tell the truth, she’s not really necessary.

one of those things that everybody just knows even if they’re not sure how. Tarzan is one such icon. Who doesn’t know the image of the handsome, wild, muscular man swinging through the jungle with the agility of an ape? Sometimes there’s a girl in his arm, but to tell the truth, she’s not really necessary.

Like many such icons, Tarzan has been unmoored from his ultimate source. Everybody knows Tarzan, but most haven’t read Tarzan of the Apes, by Edgar Rice Burroughs. When I picked up Tarzan of the Apes, I was driven more by curiosity than the hope of a good story.

Tarzan of the Apes was first published in 1912, and a century is more than enough to make a novel historically interesting. Even the novels that were radical unconsciously reflect the ideas and attitudes of their era (no one lives entirely free of his time). In this respect, Tarzan is interesting, even though what it reflects can be quite bad. The crude racist stereotypes are obvious blemishes, but the more subtle eugenicist ideas are the same poison – refined and intellectualized and so more pernicious.

This book surprised me. It is darker and more violent than I anticipated, with a surprising dose of cannibalism from both white and black characters. Tarzan’s jungle divides itself pitilessly into killer and killed, and he himself is a wholehearted participant. Most of the characters, of whatever race or species, are scum. At the same time, it is far more thoughtful than I would have guessed. In the best tradition of speculative fiction, Burroughs uses fiction to explore an idea. He takes up the nature vs. nurture debate by putting a child of the best hereditary (in an eugenicist touch, the son of English aristocrats) in the worst environment (raised by savage apes in a virgin jungle).

To Burroughs’ credit, he doesn’t offer a quick, cut-and-dried answer. Tarzan, the subject of his fictional experiment, is deeply influenced by both hereditary and environment. At the same time, Burroughs’ treatment of the question is generally unconvincing, occasionally ridiculous, and undermined by eugenicist assumptions. Burroughs explicitly grounds the explanation of Tarzan’s superhuman physicality in evolution, in the logic that human muscles and senses atrophied as we learned to rely on reason and would rejuvenate in an environment that demanded it for survival, but I didn’t buy it. Nor did I buy that Tarzan’s aristocratic genes made him instinctively gracious or chivalrous, or that he could become fluent in any language quickly. In a very real way, Tarzan of the Apes is a book of ideas. It’s just that the ideas are mostly claptrap.

As much as eugenics, as an idea, deserves to die, its presence in Tarzan is part of the novel’s scientific bent. So, too, are the references to evolution, the nature vs. nurture debate, and the way an important plot point turns on this new thing, fingerprinting. If you don’t know what that is, the book explains it. A good part of the book’s darkness comes from its more realistic portrayal of apes in particular and African jungles in general. The portrayal is not really scientific; Burroughs attributes to the apes a language (however limited) and customs and laws (however savage). But  unlike Disney’s Tarzan and The Jungle Book, which were developed out of a desire for fun, child-friendly stories with animals that talk and sing and occasionally even dance, Burroughs’ jungle society was developed in the spirit of the real jungle. The apes in this novel are violent, but so are apes in real life.

unlike Disney’s Tarzan and The Jungle Book, which were developed out of a desire for fun, child-friendly stories with animals that talk and sing and occasionally even dance, Burroughs’ jungle society was developed in the spirit of the real jungle. The apes in this novel are violent, but so are apes in real life.

To take Tarzan of the Apes strictly as art, the plot was well-constructed and the author unafraid of making decisive change in his hero and story. The love story, for once, was not completely predictable. The old professors were funny. I was still ready for the book to end in the neighborhood of page 150, and I got tired of the phrase “forest god”.

Not much of the real Tarzan of the apes survives in his icon – not his propensity to kill, his blue blood, his superhuman strength. But the image of him in his jungle is enduring. Tarzan of the Apes may be good fare for those interested in culture, history, and old-fashioned pulp romps. Reader discernment is needed, however, and the novel is emphatically not for children.

Annnnnnd for some reason, my library keeps it with the kids novels…