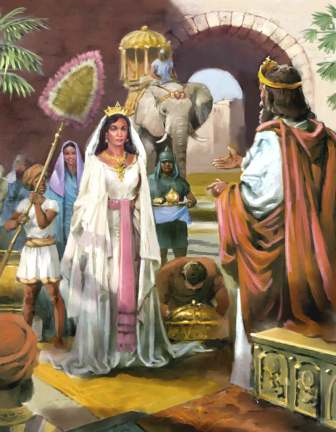

Of all biblical stories, Esther is among the best-known and most retold. There is good reason for this. It is a complete and satisfying tale, with peril and victory, with an underdog who wins, a villain who gets his comeuppance, and a  brave, beautiful heroine. Its attraction is enormous, but a curious pattern emerges among the re-tellings. Even while staying faithful to the facts of the story, many re-tellings shift the dramatic and emotional center from Esther and Mordecai to Esther and Xerxes. The story of Esther is commonly told as a romance, but in the Bible, the relationship that matters most is the one between Esther and Mordecai.

brave, beautiful heroine. Its attraction is enormous, but a curious pattern emerges among the re-tellings. Even while staying faithful to the facts of the story, many re-tellings shift the dramatic and emotional center from Esther and Mordecai to Esther and Xerxes. The story of Esther is commonly told as a romance, but in the Bible, the relationship that matters most is the one between Esther and Mordecai.

Esther and Mordecai were cousins, but their relationship is defined by the fact that Mordecai adopted Esther after her parents died, taking her in and raising her. (Somewhat-irrelevant side note: This phenomenon – family members of the same generation but of vast age differences – occurred more frequently in ancient times than in modern, for various reasons.) Mordecai was, in effect, Esther’s father. This relationship drives forward the story: Mordecai’s concern for Esther leads to his vigils at the palace gate, through which he both saves the king’s life and incurs Haman’s animosity; it is Mordecai who explains to Esther (cloistered in the palace) the plot to annihilate the Jews and persuades her to act; Mordecai and Esther together save the Jews and later establish the celebration of Purim.

Esther and Mordecai are also at the heart of the story’s spiritual and emotional power. Esther commands the fasting and prayer in preparation of her bid to save the Jews; Mordecai makes the immortal statement that she became queen “for such a time as this.” It is their lives, their family, and their people brought beneath the shadow of ruthless slaughter. It is their relationship – and emphatically not the relationship between Esther and Xerxes – that is demonstrated to be one of mutual affection: Mordecai walked in a courtyard of the palace every day to find out how Esther was after the king’s officials took her; Esther was “in great distress” at the news of Mordecai’s distress.

Esther’s relationship with Xerxes was, of course, marriage – but marriage to a despot of ancient Persia, and that is a very qualified thing. He practiced, and pretended, no sexual fidelity toward her; consider that he slept with all her rivals for the queenship and then kept them as concubines within his palace. It is evident, too, that Xerxes and Esther didn’t really live together. They only visited at such times when Xerxes wished it – and he could go whole months without wishing it. No detail more sharply illuminates their relationship than the fact that Esther was deathly afraid to go to Xerxes without his summons. In the pivotal moment, Xerxes treated her with regard, but to the end their interactions were those of an absolute sovereign and a favored inferior. Esther was Xerxes’ queen more than she was his wife (though that also, to be fair, had its privileges). It should be noted, too, that Xerxes was an alien to the spiritual concerns of Mordecai and Esther and wholly safe from the death that threatened both of them. Xerxes is an ambivalent figure at best, and a hero on no consideration.

Why, then, do interpretations of the story so often fix on the supposed romance between Esther and Xerxes? The answer is simple, a truth that has long frustrated readers who prefer fantastical stories: People would rather hear about romance. To many people, a romantic relationship – even one as distant and asymmetrical as the marriage of a Persian despot and his queen – is inherently more interesting than a father-daughter relationship, even if it saves a nation from genocide.

I think I tended to see this story primarily in terms of trying to save her people, and all the other relationships as accessory to that. Primarily because the story feels focused more on her quest rather than the relationships.

Sexual or romantic relationships tend to be something a lot of people seek out at some point in their lives, so they probably have a fascination for it just because of that. Especially since it’s something they have to work for. There’s usually a relationship with a parent at some point in their lives, but if they want a romantic relationship, they have to look for one.

Tangent: Yeah, large age difference between people of technically the same generation were more of a thing when people had more kids throughout more of their lifetime than stopping at 2-3 in their 30’s (tho there are plenty of exceptions, I’m just ballparking a mainstream average). My mom is about 12 years younger than her oldest brother, and she’s only one of five. Good little fruitful Catholics and/or weird Quiverfull peeps with 8+ kids could easily have two decades between oldest and youngest.

Yeah, I’ve known families like that. I’m the oldest out of 3, but my youngest brother is 14 years younger than me. And my boyfriend is the youngest of 3, and his closest sibling is 8 years older.

I think the reason retellings focus on the romance is because there’s so little evidence (or likelihood) of actual romance. That way they have a “but what if” to hook readers.

Granted it’s been way overdone, and anyone not familiar with the Biblical account might be surprised.

Mostly, it’s just because romance sells (and I say that as someone who loves romantic stories). But, yeah, overall Xerxes/Esther is icky.

I think Ruth/Boaz is just about the only romantic (or “romantic”) story that isn’t actually pretty gross when you think about it.

Not really sure Ruth x Boaz is entirely free of ickiness, either, though. People’s lives were hard back then, so people seemed to have to settle a lot, even if a marriage or circumstances around it weren’t optimal.

True enough. Guess that’s another reason why there’s such a good market for the bonnet-rippers

I think you imagining that anything in Ruth/Boaz is gross in any measure would have to come from a misunderstanding of what the book is about. It certainly seems to me to show a misunderstanding of the culture of the time. You could say that Naomi sending Ruth to the threshing floor to lie next to Boaz was a rather clumsy attempt to get her to seduce him–and would qualify maybe as gross (though I’d say it was desperate rather than gross). But Ruth obeys not because she is a bad person, but because in her culture, submitting to the wishes of her adopted mother was a “thing.” And Boaz flat-out turns down any opportunity to take advantage of the situation and seeks to marry her, after already clearly admiring her. The bottom line for the story is that both Ruth and Boaz are exceptionally honorable people and the story makes it plain they deserve each other. That’s not romance in the modern sense, which focuses on bodies a lot–which is kinda gross, actually. In fact, I’d say that Ruth/Boaz is far less gross than virtually any modern romance story.

Esther is not really romantic and definitely reflects a past culture. Being the chief wife among a harem of wives (as Esther was) just reflects the realities of another world–I totally get why a woman would not want to trade lives with Esther. Her life was kinda awful, actually. But calling it “gross” or “icky” seems to me to kinda miss the point…though what I am saying requires someone to realize the story is in no way a romance, even if the king found Esther more beautiful than all the other wives in the harem…

No, I’m very aware that romance is a fairly recent invention. But a situation can be normal in context to the culture and times and still be “gross” in the (casual) modern sense at the same time. Or maybe that’s too postmodern of me.

That Ruth WAS desperate and forced by circumstances is pretty gross even if Boaz specifically wasn’t gross and it ended up fine. I guess I’m not being terribly specific between calling a situation gross and calling the people and their actions within that situation as being gross. Or what exactly I mean by “gross.” Lots of grossness to go around in either case.

Part of it depends on how we define gross. I kind of took it to mean whether or not there’s potentially messed up aspects in the relationship. Ruth x Boaz sounds like one of the better couples in the Bible, but it’s by no means perfect. I somewhat feel sorry for Ruth because there’s a possibility that she may not have really cared for Boaz that way or wanted to be with him. That can be a rather stressful situation for someone to be in, yet, if she did dislike the idea of being with him, she agreed to anyway because of circumstances.

That’s part of why I pointed out the aspect of settling. She may have settled for Boaz because of tradition and to pull herself and her mother in law out of poverty, even if it may have been very unhappy or disgusting for her. There is a possibility that she didn’t mind the guy, and I hope that is the case, but who knows if it was.

That was excellent Shannon; great analysis. I wonder if, in a broad sense, people (the royal we) a) don’t want to hear about father-daughter stories, or b) have so few good examples in their lives to draw the right story arc for a good father-daughter story, and therefore, we just don’t have many and prefer romance as a quick fix? I think, deep down, we do want to hear stories that portray positive “but what if’s”. What if a father sacrificially loved his daughter and help her work toward her best self, creating the environment for her identity to flourish? What if a daughter grew up in that environment and was supported through her trials? For a dad to walk alongside his daughter in the midst of them?

Whenever I reread Esther, I can’t help but think “This is the same Xerxes from 300.” Nope, not romantic.