Can Christians Write Novels Without Evil?

Is it even possible to write a Christian novel without evil? Not really. I suppose one could write of unfallen other worlds, the pre-fall Garden of Eden, or of the saints in Heaven and get away with it. But that’s not the world we inhabit or anything remotely close to it. And, as a friendly, jab, best wishes on your conflict in Heaven!

To the contrary, I’d argue that evil is a central component of the Christian worldview. Any character that is genuinely Christian must face it and face it even within their own being, Wesleyan Holiness types aside. After all, who will deliver me from this body of death? Thanks to E. Stephen Burnett, I’ve been presented an opportunity here to discuss some of the issues regarding evil and Christian fiction.

Christian fiction written without evil is truly a Christian fiction, in that it has no tie to reality as professed by Christians. It ceases to be Christian, outside of the possible exceptions presented above. A novel without evil is a non-Christian mythology, a way of understanding our world at the deepest levels that bears no relation to the truths taught by Christianity.

Fortunately, it’s good news that the logical problem of evil is widely thought to be solved by thinkers of all stripes, largely due to the work of Alvin Plantinga. The logical problem of evil differs from evidential or probabilistic versions of the argument in that it attempts to detect a contradiction or incoherency between the propositions God exists and evil exists. After two millennia or more, it is now commonly accepted that the proposition God may have morally sufficient reasons for allowing evil is sufficient to dispatch the logical POE.

So, the question for us as Christian writers is something along the lines of the following: do I have morally sufficient reasons for writing a Christian novel that contains evil? I think the answer is not only a resounding yes, but that evil is required. Here are some reasons why (keep in mind the above disclaimers)…

- A Christian writer ought to be faithful to the revealed Word of God, which describes our world as evil.

- For Christian writers to create characters who possess no evil qualities is tantamount to denying Scriptures such as All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.

There are more we could list, but that should be adequate for the moment. The existence of evil in Christian literature is really not that contentious. What is, however, is the existence of gratuitous evil. Gratuitous evil is any evil that does not appear to have a role or purpose in the story. It is evil for evil’s sake, so to speak.

Interestingly, this is one of the philosophical reactions to the fall of the logical form of the POE discussed above. There are some forms of evil in the world, it is argued, that are gratuitous evils that God could not have a morally sufficient reason for allowing. A classic example of this is the fawn that dies horribly in a forest fire. What possible reason could be offered for this type of evil? Certainly not free will or the soul-making property of evil. Rather than offer a defense here, let’s take a moment instead to look at the problem in light of Christian fiction.

Is there an instance in your writing, or mine, where evil is inserted gratuitously? Does it serve no purpose in the development of the characters, the general tenor of the created world, the spiritual theme, or the story at large? If so, this is probably a good example of an area where evil does not belong in Christian fiction. The point is this: have solid reasons why the evil you insert into a novel is required by the world and story itself, and offered pursuant to that taught in Scripture.

But that’s not all. Intertwined with evil and fiction is the existence of violence. You may have evil without violence, but often they appear together. Is this acceptable for a Christian novel, given that the violence portrayed is not gratuitous? I believe so, and I believe it’s fairly easy to demonstrate.

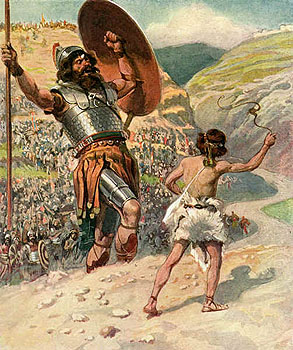

The Bible is an extremely violent book. There’s Jael and the tent peg, there’s David beheading Goliath, there are bears mauling kids—young men, most likely—at the command of the prophet Elisha (those of you who taunt my thinning hair should be glad I’m not Elisha…you know who you are!), and literally hundreds of other violent acts that upset our delicate, 21st century PC sensibilities. Even God gets in on the act with frequency: I will make my arrows drunk with blood, while my sword devours flesh.

Our choices are to accept the Bible as the authoritative, infallible, inerrant Word, including its violence, or not. I for one choose the former and think it is high time we quit making excuses for it. In like manner, as long as violence within a Christian novel is not gratuitous, is genuine with regard to the created world and story, and displays Christian truth, it is acceptable.

After all, why is the Bible so violent? The answer is simple, yet important: God cannot lie; thus, He describes our world and our hearts exactly as they are. Imagine if God had not done so out of fear he might offend someone! Heaven forbid.

Lastly, the most violent event of all time—yes, more violent than the worldwide flood that killed all but eight or the eschatological violence looming ahead—is the crucifixion, in which God poured out his wrath on His perfect son. Why? Why would God write such a violent story? And make no mistake, He did write it.

True, we are not God, so we must take utmost care when handling such powerful themes. And please hear me clearly: evil and violence are never to be glorified. They ought to be described as the hideous realities they are, and they should never be focused on solely to the exclusion of the Good. But I also believe God wishes us to tell the truth about this world, about the hearts of men, and about how His glory shines ever clearer through it all. May it be so.

Marc Schooley is a Texan, which may be empirically verified if you ever hear him speak. He is a Christian philosopher, theologian, Bible teacher, speaker, musician, and nascent Christian fiction writer who welcomes you to communicate with him at www.MarcSchooley.com, featuring quest appearances by MS Quixote—which may or may not be his alter ego (a special commission has been established to investigate this matter). His novels The Dark Man and König’s Fire blend action and paranormal twists with in-depth characters and Christian doctrines.

Well written article. I would add one thing, when it comes to the portrayal of ‘supernatural’ elements, contain it to appropriate characters.

Lewis and Tolkien confined the elements of the supernatural to character representative of the God and Satan. Dabbling beyond that is problematic and can cause a slippery slope.

Mortal man cannot wield magic through themselves. I don’t mean objects like rings and such, rather like Harry Potter or Star Wars where the ‘physical nature’ of the individual is born to command the supernatural.

Hey Shawn,

It may be a bit more complex in settings where the world rules are intentionally different, or where apostles are written about, etc., but all things being equal, this is a great comment. It’s a healthy reminder to keep theology straight in any work of fiction, or non-fiction, for that matter.

Now, I’m most likely going to irritate someone. I would take your thesis and advance it to say it’s problematic for Satan to be granted miracle-working power as well. False signs and wonders, yes. Genuine supernatural, miracle-working power? That would make Christ’s statement “believe the miracles, that you may know and understand that the Father is in me, and I in the Father” arbitrary and not at all authoritative, don’t you think?

I don’t know, Marc. The medium Saul went to did conjure up Samuel. Pharaoh’s magicians did turn staffs into snakes. The demon possessed girl apparently did foretell the future and the demon possessed man did have supernatural strength to break chains. I don’t think we can ignore that Satan does have power. He doesn’t have all power and what he does with his power, God allows. But he’s not reduced to tricks. He is a formidable adversary who requires the armor of God if we are to stand against his fiery darts.

Shawn, I would suggest that Harry Potter is not in the same camp as Star Wars. The latter clearly identified the supernatural as the source of power. The former does not. Power is what wizards and witches in that world have by birth, much as we have athletic ability or competence with numbers. It was a talent that needed to be refined by education and practice. No outside force was ever called upon to bring or enhance that power. It was not supernatural, but quite natural for those born with it.

Becky

“those of you who taunt my thinning hair should be glad I’m not Elisha…you know who you are!”

Why yes, I do…but seriously…”thinning”? Dude, that’s a bald spot. Totally. And anyway, you’d never sic the bears on me; I also know how you feel about bears.

You make absolute sense. There is so much evil behavior inserted into books to make them sell, at the behest of publihsers much more than from the inspiration of the writer, that it is difficult to get a book published which deals with evil and with authentic Christian values. That’s why J.R.R. Tolkien and J.K. Rowling have done us all a wonderful favor: they were successful in dealing with the nature of evil and how it affects all of us.

Please visit my blog and leave a comment. Thanks!

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Timothy Stone, Speculative Faith. Speculative Faith said: Author Marc Schooley: Truly Christian novels must include evil, but not for its own sake. On #SpecFaith: http://bit.ly/hezduP […]

Marc said:

“I would take your thesis and advance it to say it’s problematic for Satan to be granted miracle-working power as well. False signs and wonders, yes.”

Becky said:

“The medium Saul went to did conjure up Samuel. Pharaoh’s magicians did turn staffs into snakes. The demon possessed girl apparently did foretell the future and the demon possessed man did have supernatural strength to break chains.”

Can I go out on a limb and agree with both? I think it may depend on the definition of a miracle. I’ve heard two different ways of looking at it since entering the Christian culture. One states that a miracle is defined as a special act/intervention of God in the course of the world (which may or may not appear paranormal), and the other defines a miracle as anything which appears to act outside of or in contradiction to the known laws of the universe (emphasis on “outside” and “known”).

The first inherently excludes Satan from the working of genuine miracles. The second groups the supernatural arena of God’s workings with deceitful paranormal phenomena (lying signs and wonders), and inherently excludes non-paranormal divine intervention.

Either one may be a useful way of examining the question depending on the theological topic under discussion. Held as default positions from which to think, they may cause apparent disagreement where views are in fact harmonized with relative ease.

Totally agree w/ the reasons for including evil in novels. Hadn’t really thought about it, but still…

I love the “Lamb Among the Stars” trilogy by Chris Walley because his portrayal of evil insidiously creeping into a perfect society is so fantastically creepy. It made me think about how I deal with the influence of evil in my everyday life. That couldn’t have been done without putting evil in the novel.

Excellent article! Thanks for linking.

This is a great thing for me to read. I’ve been working on a fantasy novel that I’ve actually felt God has called me to write, and I’ve really felt that the way I depict evil, raw and even creeping into the minds of certain protagonists, would make it unsalable to Christian publishers. I haven’t given up on it, since I believe God wants it shown for what it is and to those who read this genre.

I have to say this first: I don’t care what anyone says, Wesleyan Holiness types are the ones who believe we MUST face the evil within ourselves, and through our lifetime, allow the Holy Spirit to free us from the sin that enslaves.

To the actual content of the article, I do think what you’re saying here is the theological equivalent of Orson Scott Card’s suggestion that we build the underlying principles of any science fiction we right, so that it’s consistent and believable. In the same way we must understand how we travel through space, we have to know beforehand how we’re dealing with sin.

Hey Jeremy,

My mention of Wesleyan Holiness was not a criticism, nor do I think Wesleyans ignore evil. What was intended, conversely, was that in accordance with the Wesleyan doctrine of imparted righteousness, in stark contrast to imputed or infused righteousness, the sin nature is actually crucified in Christ. It’s dead and no longer present. Thus, a Wesleyan author could conceivably write a Christian character who does not face evil within her own being as exemplified by an ongoing, active, sinful nature warring against her regenerated self. For many Wesleyans, the question who will deliver me from this body of death is not simply a rhetorical device, nor is it one that describes a present reality within regenerated persons.

Marc,

Alas, this example is not hypothetical.