Christians, Your Neighbors Don’t Get God’s Grace

When Christians in their stories, songs, and discussions mention God’s Law, non-Christian neighbors don’t have a clue what Christians are talking about.

They also don’t get Christian “code” language about repentance, sin, death, and hell.

Fortunately, some other Christians (or professing Christians) understand that non-Christians don’t understand these concepts. These Christians know their non-Christian neighbors interpret these concepts as expressions of hate, guilt, doom, and power plays.

So their solution? Stop talking about God’s Law entirely.

Their solution is to assume their neighbors know all about what God’s grace means.

Several readers of this Franklin Graham post tried this “solution” in the comments section. This “solution” also pops up in conversations, books, novels, songs, sermon series, and blog articles that purport to explore how Christians should Engage A Post-Christian Culture.

One Graham critic used this assume-grace Christian code while making this assumption:

Shame on you, Franklin. Your dear father, Billy, would never have stooped to this level of vitriol against humans we have been commanded to love, not judge nor condemn, and certainly hurl no stones. Islam’s Taliban is a poor example for you to follow. Your father and our dear Lord provide a higher example.

Phrases like “we have been commanded,” “judge or condemn,” and “hurl … stones” are biblical references, particularly to the account of John 8:1-11.1 So the writer is trying to speak from a Christian perspective.

But the writer does not seem to understand none of this will be any help to non-Christians.

2. Non-Christians do not understand God’s grace

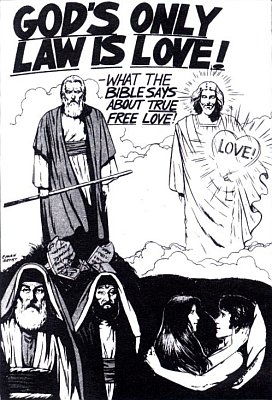

Such slogans as “God’s only law is love” only make sense in Christian subcultures. They provide no sense or comfort to the person who hasn’t a clue about the biblical concept of God’s Law.

I’ll spend more time with this problem because I see it far more often in Christian cultures.

Here’s how the problem breaks down. A Christian is in a discussion with other Christians who are acting mean (or supposedly acting mean). In response the first Christian assumes:

- My non-Christian neighbor has had the same struggles with legalism as I have.

- That other Christian is acting legalistic, like the mean Christians I’ve met before.

- My neighbor feels enough guilt as it is. Someone else already made them feel that way.

- I don’t want to do that. I want only to reach my neighbors with God’s love and grace.

- So I’ll talk about Jesus’s grace and acceptance, which everyone (like me) would love.

- Non-Christian neighbors will see the contrast, and consider embracing Jesus.

To be sure, there are many legalistic and nasty Christians who need to be critiqued (but first with Scripture, not sentimental appeals). Their false ideas and un-Christlike behavior should be naturally challenged and exposed in stories and songs. And in some cases, such “mean Christians” do mean well, but their jargon and assumptions betray their insularity.

But Christians who assume non-Christians easily get biblical concepts of grace, love, and mercy are just as insular.

But Christians who assume non-Christians easily get biblical concepts of grace, love, and mercy are just as insular.

They don’t have a clue how non-Christians really interpret these terms.

Sure, most non-Christians are (wrongfully) repulsed by the idea of a loving yet disciplining, holy, judging God. They may claim they’re perfectly okay with a “loving” or “accepting” God.

But when many non-Christians hear Christians bring this assurance—“God isn’t mean or nasty! In fact He is very loving and accepting of people”—they are not always thinking like Christians think. They aren’t always thinking, “Finally, here is relief from this guilt I have under the burden of sin and the Law.” They aren’t always thinking, “At last, Someone Who can forgive me!”

Instead, at best they are thinking, “Good. At least some Christians will accept me and won’t ever challenge my sin with this ‘Jesus’ stuff.” And at worst (especially if they are political power-player types) they are thinking, “Good. Here is a Christian who is a useful idiot.”

For those Christians who try the “grace and acceptance” approach alone, trying to find common ground with non-Christians, I must be firm yet truthful: Many non-Christians simply do not understand your journey from sin, to legalism, to forgiveness. They can’t care about or identify with any of that. They view “legalism” and “good purpose of God’s law” as one and the same thing—something evil to get away from, by pretending it doesn’t exist.

Applications to fiction

Alas, when Christians do not understand this fact about our non-Christian neighbors, we grumpily or cheerily head out to combat or “love” our neighbors without having a clue.

And some of us write stories in which we attempt to “evangelize” imaginary beings.2

Not all Christian novels are this way. We need to stop pretending they are. But I have read some of them that are still like this: They are written by, published by, marketed to and sold to Christians, but are based entirely around the story of an imaginary non-believer.

The secular character serves as wish-fulfillment for some of our over-sheltered evangelical desires. He/she is convinced by soft-soap clichés, such as “just take a leap of faith.” Or the secular character hears a good-cop-Christian assurance like, “Yes, God really loves you,” and are led to sentimental tears, rather than confusion or eye-rolls. Such secular characters act as if they somehow already understood the Law, which would mean Grace comes as a relief to them. But of course, in such stories, the Law doesn’t even make a cameo.

So what’s the solution?

One offered solution might be, “Christians shouldn’t share stories or conversations about specific spiritual concepts like law and grace. After all, Just Tell the Story.”

But we may as well claim, “Write a novel, and if necessary, use words.” Law (and sin, guilt, repentance, punishment) and grace (and love, mercy, forgiveness, atonement) are crucial to all stories, and to the reality biblical Christians live every day. Without reflections of law and grace, there is no plot. Without a plot, there is no story—either in fiction or in reality.

Thus our stories, songs, and discussions must include these concepts.

But we must be wiser about how we explore these reflections, not only to a wider non-Christian world but to Christian who are themselves confused about law and grace.

We cannot assume our non-Christian neighbors will get either God’s Law or God’s grace.

And we absolutely cannot leave one or the other out of our stories, songs, and reality.

How have you seen God’s Law and God’s grace best communicated, especially in stories? How have you reflected these beautiful truths to the non-Christian neighbors in your life?

- Jon Bloom writes a truthful and imaginative exploration of this account at Desiring God Ministries that dispels some evangelical myths. ↩

- I’ve touched on this in part 4 of a previous series, Fiction Christians From Another Planet! ↩

Except I’ve never heard of anyone who converts for apologetics reasons. They convert more for emotional reasons, because they’ve found a community, and the apologetics come afterward. CS Lewis’s Christian buddies came before he was Christian again. My dad’s family were traditionally Methodists (with a Methodist circuit-riding preacher in there), but he ended up growing up in the Disciples of Christ church and staying there because people there went to the effort of making them part of the church-family.

No one converts for “purely” apologetics reasons, that’s for sure.

But then, no one truly converts based purely on emotional reasons either.

Biblical Christianity is based an the announcement of a Fact: Jesus Christ lived, died, and lives again, and this was His mission, and here is what you must do.

This invites emotional response. But it is not limited to emotions or apologetics points.

For the biblical Christian attempting to share the Gospel with words and deeds, we cannot assume or devalue either emotional appeal or “apologetics” points such as “This is what the Bible says about Jesus, this is Who He was,” and so forth.

Stephen, again you raise the bar of “consciousness” if I may use the term. I would like to note that when the Way first appeared, especially in the Gentile world, many of them didn’t “get” it either. In Acts 17 Paul is laughed off the Areopagus because they think he’s preaching foreign deities, the male god Ho Yesous and the female goddess He Anastasis. So a “major disconnect” occurred in their thinking. The people of the first century didn’t understand Law and Grace either, but that did not stop Paul and others from proclaiming the Gospel. My concern is, as always, not to throw the baby out with the bathwater. The best way to evangelize — for me at least — is to so live my life before men and women who don’t know the Lord that when He gives opportunity, take it. I waited a very, very long time indeed at my job for the right moment — but it came, and so did the precise words I was meant to say. What that person does with the Truth is not my affair, only to be faithful. I agree with you wholeheartedly we need to amputate sloganeering from our lives. But when we get the opportunity, let’s ensure we do things God’s way by sharing the whole counsel of God, which involves love and grace but also sin and judgment. Like you, I deplore the remark cast at Franklin Graham. But his father never shied away from telling the lost that’s what they are, lost and doomed without the Son who died for them. So much of what passes for American “evangelical” Christianity no longer speaks of sin, no longer speaks of repentance, squirms and kicks at the very synapse that God might be “angry” about anything. Stay true. Don’t succumb. Swim against the flow. Engage, but according to the scriptures. Thanks again for raising that bar and making us take a hard look at how we express our faith to those who do not know Him.

So true. Randy Alcorn wrote a great book about grace (mercy & forgiveness) and truth (law and consequences). Truth without grace kills; grace without truth also kills. Living completely under grace is like trying to survive on cotton candy. You can’t do it. Thanks, Stephen and HG, for reminding us that we serve a mighty God who has a powerful Son and an awesome Holy Spirit, not a weak and wimpy God whose Son simply whispered, “It is finished” and then died. IT IS FINISHED. AMEN!

C. S. Lewis pointed out this difficulty in evangelizing moderns in his famous essay “God in the Dock”. He pointed out that the nearly universal assumption of pre-modern peoples was that they were sinners and needed to appease the gods and to approach them with humility. The unique doctrine of Enlightenment humanism is the assertion that men are essentially good and it is God who needs to justify His demands upon them. The unfortunate consequence of this absurd assumption is that Christian cannot lead with the Good News of the gospel. Moderns don’t see the need of a savior. So often we must first convince them of the reality of the righteous law and the reality of sin, before we can bring the good news of grace. However, this is for the most part just a theoretical, intellectual reality. I believe that for many this belief is fairly superficial. The deep existential feeling of our separation from God and of our need for meaning and love often bring moderns to cross. I certainly did for me.

I’d quibble with that assumption that pre-moderns thought they were “sinners,” per se. Your everyday average Joe wouldn’t feel that he was a sinner if he hadn’t done anything (e.g., non-Christian connotation of “sin”), and respecting gods that you believed could smite your butt on a whim was just common sense. Superstitious, but common sense in a superstitious way. Original Sin is a Christian concept, and not even a universal one among Christians, because Eastern Orthodox doctrine doesn’t have it. Jews don’t, and Muslims don’t, either, so it’s not even common among monotheists.

** They don’t have a clue how non-Christians really interpret these terms. **

To say “non-Christian” as though that encompasses a single conglomeration of beliefs and experiences and understanding is a very sweeping statement, and I argue an unsupportable one.

I have non-Christian friends who are atheist, agnostic, Muslim, ex-Christian, Christian-in-name-but-not-in-belief, straight, gay, bi, drag queen, pick a label. Those people all have various different experiences which certainly don’t lead to a universal interpretation of terminology.

To your point, however, I think this just means that we have to be personal, rather than issuing broad evangelical declarations and considering our missionary work done.

Laura, that’s just the point. Too many Christians are certain they know what they mean by these terms. But non-Christians are, in fact, interpreting them in a variety of ways. Their views may be closer to the Christian understanding of these concepts, or far from them. But they won’t have the universal experience, shared and possibly projected by some Christians, so they can think, “Oh yes, when the Christian says ‘Jesus isn’t about religion, but relationship,’ I know exactly what this means because I too have had a life-transforming journey away from pleasing God through rule-keeping.”