Define ‘Christian Speculative Story’

What is this thing called Christian speculative fiction?

Readers and writers are still debating those definitions, and I think that’s okay.

The most recent instance was Monday at this site, in the comments here. Rebecca Miller admitted her original question was more broad, about which Christian speculative stories — besides Lewis and Tolkien — would be considered required reading. Still, some of the submissions were from a wider field of reading than what most would consider “Christian.”

To prove that, we must define Christian speculative fiction/stories. How do you define that?

Here’s a possible pattern for discussion:

- Write a short definition of Christian speculative fiction/stories.

- If you like, break down the words and phrases with sub-definitions.

- Any bonus comments, with evidence or preemptive rebuttals of criticisms.

Here’s what I mean.

1. Definition of Christian speculative stories.

Here’s my working definition for discussion/revision.

Christian speculative stories are fantastic tales that are written, or otherwise shown, clearly yet naturally from a Christian worldview. That is, the hero and plot reflects Christ and the Gospel, the characters reflect real people, and the story-world and style reflect reality and God’s truth, wonders, and creativity.

2. Phrase breakdown.

Christian speculative stories are fantastic tales

- We’re speaking here of story-worlds including things we don’t normally see: fantasy, technology, creatures, alternate histories, miracles, and so on.

that are written, or otherwise shown,

- These include novels, television, plays, motion pictures, and so on.

clearly yet naturally from a Christian worldview.

- What this means: the hero/plot, characters, and world run on Biblical “rules” — not necessarily God’s “will of command” or revealed will, but His sovereign will (e.g., sin brings consequences, we don’t always have answers this side of Heaven, He is God).

- What this doesn’t mean: every character finds God or finds answers to every question.

- What this means: the author is knowingly telling the story according to Biblical “rules.”

- What this doesn’t mean: the author is clearly a professing Christian (but I’m not aware of a case in which a non-Christian author wanted to write a specifically Christian story).

That is, the hero and plot reflects Christ and the Gospel,

-

"The Avengers" has a basically Christian worldview, true heroism, and self-sacrifice. But is it a "Christian story"?

What this means: the hero in some sense is a Christ-figure, and sin and grace are seen.

- What this doesn’t mean: any hero, even if he sacrifices himself, counts as a Christ-figure.

- Example: the alternate gospel “story” of Mormonism, a fantastic tale with other planets and everything, is not the original Gospel. This goes beyond intra-Church debates over baptism or “Calvinism” vs. “Arminianism,” for the Mormon concept of Jesus and His mission, the Gospel, is skewed to the point of being a false “Jesus” and false “gospel” (Galatians 1: 6-9). For more, see here.

the characters reflect real people,

- As in reality, characters behave like actual humans, not one-dimensional clichés. They show the Biblical truth that man is sinful, yet can be redeemed, and that even sinful people can do good, even if they have bad motives (Matt. 7:11).

and the story-world and style reflect reality and God’s truth, wonders, and creativity.

- What this means: in such a story, God is “seen,” even if He seems hidden. He’s shown in a way that nature itself reveals Him. “His invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse.” (Romans 1:20)

- What this doesn’t mean: God and His nature are seen just as clearly as He is revealed in the Bible. Scripture is final, only-certain revelation from God Himself. So no speculative novel need also try to act like the final, most-comprehensive word on the subject.

- What this means: the story includes truth, not always accessible or resolved or seen, but always present — even behind the scenes, even just out of reach.

- What this does not mean: beauty in style and craft don’t matter if the story has truth.Truth without beauty is a lie. Beauty without truth is ugliness.

3. Bonus: why read newer Christian speculative stories?

Becky later asked this question:

I’m beginning to wonder–we have a lot of writers who stop by, and readers who read general speculative fiction, but do we also have visitors who read “Christian speculative fiction”–the books we have here in the Spec Faith library, the books many of our guest bloggers write?

I’ve also begun to wonder if Christian readers are reading anything besides classic fantasy — works by Lewis, Tolkien, MacDonald, etc. — and secular speculative novels. Recently I had to razz a friend from church who was only recently pushed into reading The Hunger Games. His reason: it wasn’t Lewis or Tolkien, so why read anything else?

I’d rephrase his question, and not only because this brother happens to lead the singing at my church: it isn’t by Isaac Watts or Charles Wesley, so why sing any other song?

Rather, God should be worshiped with “a new song,” played excellently (Psalm 33:3).

And if worship is more than singing, and it is, we must also enjoy new stories for His glory.

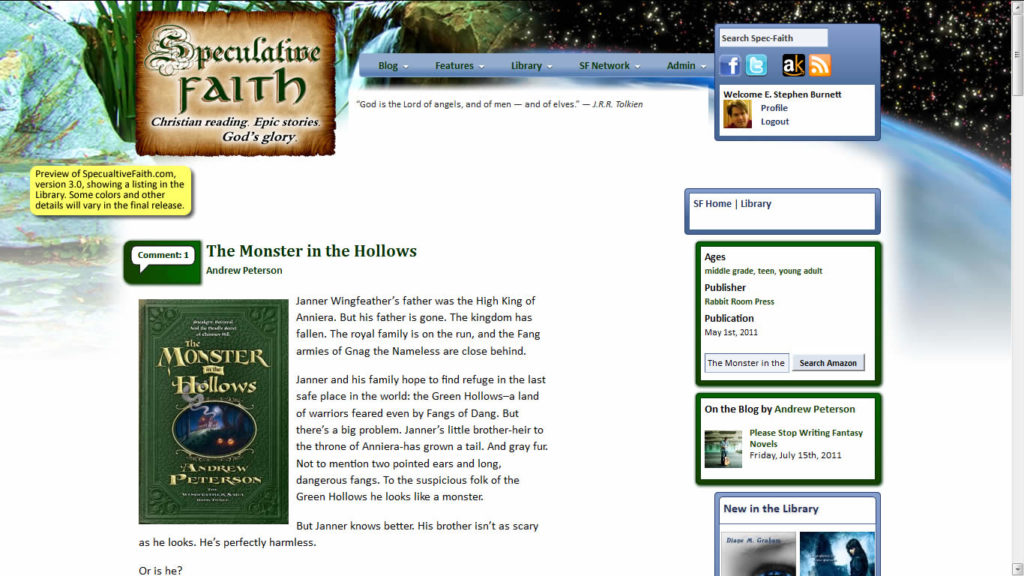

Browse our Library shelves. On June 1, we’ll launch an upgraded Speculative Faith, with new cross-reference options, organization, and featured reviews. It’s the best way we know to find new authors and novels, similar titles, and fantastically unique means of worshiping God — not only with classic fantasy or secular books, but with Christian speculative stories.

I’m slightly surprised that I have no disagreement with this definition. This definition describes what I try to find in all speculative fiction. I have not cared about classifying Christian speculative fiction separately from general speculative fiction, only about identifying and rejoicing in universal Christian truths and themes in stories, about discussing how all good stories reflect Christian truth to some degree. This definition might change my mind; maybe there really can be a category for Christian speculative fiction.

In Monday’s column, The Wheel of Time series was mentioned in a couple comments. I’m a fan of that series, and I believe it fits this definition of Christian speculative fiction. I wouldn’t have named it before, since it’s general market, and I thought the purpose of defining CSF was to identify a community of Evangelical Christian writers who market their works to Evangelical spec-fic fans despite having different goals for the Christian element in their works. (This was why I wasn’t interested in defining CSF.)

I can make many general market speculative fiction stories fit this definition of Christian speculative fiction; I can often find these elements in them if I want to see them. With some works, this takes more wrangling than with others. It requires little wrangling to see these elements in The Wheel of Time for me. By comparison, it’s even easier to see The Lord of the Rings in this definition.

My own simple definition, off the top of my head: “A Christian speculative story is one which explores ideas of fantastical things that do not exist in the real world, and is also told from a Christian worldview.”

By “a Christian worldview” I mean that the story operates under the basic assumptions of that worldview, i.e. there is one almighty and powerful God who created everything, there is such a thing as absolute right and wrong, the world is fallen and human beings are all sinners, etc.

I would only disagree slightly with part of your definition, Stephen, in that I don’t think the hero/heroine of a story needs to be a Christ-picture in some way in order for it to be Christian speculative fiction. Sometimes the Christ figures in stories are side-characters, or there are multiple small pictures of Christlike sacrifice from various characters throughout the book. (Frodo suffered to rid the world of great evil, yet Gandalf was the one who died and rose again, and Aragorn was a king coming into his kingdom…within LotR we have many little Christ pictures, but I wouldn’t say any one protagonist is a direct Christ figure, per se.)

I also don’t think a story needs to have realistic characters to be Christian speculative fiction. It could still be CSF even with wooden, shallow characters…it would just be really BAD CSF. 😀 I think it’s a little unfair to imply that poorly written books are not part of the genre because merely their authors lack writing skill. Maybe that’s not what you meant, but I thought I’d toss in my two cents…

HURRAY! The edit button is back!! Thank you to the webmaster…!

I am now editing this comment to add that the upcoming SpecFaith update looks pretty nice, too! 🙂

Great comment, Bethany. I have only read the comments up to this point, but I agree completely with what you said.

Becky

Thank you for posing this question; I’m curious to see what everyone has to say!

I’ve never put my definition of Speculative Fiction into words, but I’ve always imagined this genre as separate from fantasy, for some reason. For example, fantasy contains all kinds of supernatural events, fairies, glowing swords, and elements like that; while Speculative Fiction focused more on alternate history, or exploring “what if God worked differently on another planet/world,” or “what if the world was created differently; how would that impact life now?”

I would also say that your criteria of characters reflect real people, and the story-world and style reflect reality and God’s truth, wonders, and creativity should apply to every genre outside of Speculative Fiction. (R. M. Ballantyne does that extremely well in his historical fiction novels!)

Honestly, I don’t read much Speculative Fiction, either new or old (with exceptions) simply because I’m not sure I agree with the content of the books I research. I have very high standards for fantasy–and if a book crosses the line, it’s out. Or if it seems to cross the line, it’s out. That, and I have such a vast library already, there are plenty of titles to keep me happy (not to mention limited bookshelf space!). I read Tolkien and Lewis (also Lewis’ non-fiction), Sir Walter Scott, R. M. Ballantyne, Wilkie Collins, Charles Dickens, Ray Bradbury, Lloyd Alexander, Allen French, various miscellaneous titles, and Shakespeare. Shakespeare to the point that, in sooth, his language and style oft creeps into my own words and there takes up abode.

[Exit] 🙂

Blessings,

Literaturelady

I think your basic definition works, Stephen, as does your quibble over the presence of a self-sacrificial Christ-figure not being perhaps good enough as the sole definition. IN Western Literature, the self-sacrificial hero is a very common trope, as he is a very respected concept in Western culture and history.

That said, I do think that the definition must be more open at times. The main character being someone who struggles with faith and goes through a spiritual journey (within his fictional world’s religious structure) is a hallmark (to me) of speculative Christian fiction. I say this because most secular fantasy has what tvtropes.org calls the trope of “Devil by no God”. Essentially, they have a Satan analogue, but no God analogue, or else the God analogue is evil as well.

Looking at fantasies, the idea of a good and holy God or Creator that empowers the hero(es) to fight the Devil figure is unique in fantasy. As is teaching notions that specifically reference Bible doctrines. The Wheel of Time deals with the champion of the Creator facing the Dark One (devil figure) to stop the DO from destroying history and reality. The Attolia series deals with the will of God, and even a Providential destiny, via the fictional variants of the hero’s gods.

Sanderson’s Mistborn has the main characters being the prophesied one and her husband who sort of fills out the prophesied role with her. A side character, who is a main character, but below the main two in importance goes through horrible doubts of his faith due to tragedy and seeing his faith not be fulfilled, as well as wondering how God can allow suffering. At the end, he discovers that he, not the other one he thought was the prophesied one, is the “hero of ages”.

I would say that my definition is where, despite the author’s views, Christian speculative fantasy “reflects” a Christian worldview or Christian ideas. I think this definition being looser is necessary because it allows in more good works while still excluding works that have little value to the Christian. Also, technically under a strict definition, while Lewis would qualify with Narnia, Tolkien would himself (given his ornery nature of applicability versus allegory) have argued against including his work in Christian spec faith by your definition. I think mine is loose enough to include important works, including LOTR.

An addendum to my previous work. It may seem unnecessary to add this part, but just in case, I will. If an author (who is not a Christian) somehow has Christ infused in his work, but trashes the Bible, or some such coughTerryBrooksinWordandVoidorLegendsofShannaracough, then that does not count. The rest of his work before the past ten years is better. And trust me, there are authors out there that seem really neat in having a Christian POV or Christian ideas, until they put in something stupid and then they become useless to a believer.

Timothy, I have to agree with you. I like Terry Brooks. But his recent books are not his best, and I really hated his seeming attack on marriage.

I think I mostly agree with your definition in the article, though I might agree even more with Timothy Stone ‘s definition.

I also agree with Bethany A. Jennings. I don’t see why the hero, or any of the other character in the book really, would have to be a Christ figure for it to be considered Christian SpecFic. The Old Testament, for example, doesn’t have a “Christ figure” since Christ hadn’t come yet, and that’s the Christian book and our main example for anything related to God. And today, there isn’t really a Christ figure here on Earth because Christ has already died and risen. A modern novel might not have any specific Christ figure present, because of this. So, if there are examples in books outside of SpecFic where no Christ figure is present, surely there would also examples inside fiction that is actually speculative.

Some brief thoughts and clarifications on the Christ-figure concept.

From Bethany:

On this I should have been clearer. In such stories where the heroes or heroines, e.g. the central characters, are not particularly Christlike, or are and remain “nonbelievers” (or a fantasy-world equivalent) throughout the story, Christ Himself is the Christ-figure.

One example may be The Silver Chair, the fourth in The Chronicles of Narnia. Eustace and Jill “muff the Signs,” repeatedly, which Aslan had given them for their quest. Still they succeed in their quest, only barely, and thanks to the mercy of Aslan. But they don’t need to be Christ-figures, but He is Himself the Christ-figure.

Even if He is unseen, a Christian speculative novel has a Christ-figure. And as Bethany pointed out, even if He is in some sense “distributed” as in The Lord of the Rings, Christ is there. Even grace and truth, which are found only in Him (John 1), reflect Him.

From LiteratureLady:

I agree; that would suit a working definition for the often-elusive term Christian fiction.

From Timothy:

A clarification: I do believe this motif or theme reflects Christ, but only dimly or in a shallow way. Again The Avengers provides a good recent example through the self-sacrificial actions of its heroes. At the end (spoiler caution), Tony Stark / Iron Man commits himself to a short-lived but nevertheless self-sacrificial act. Does this make him a Christ-figure and the movie an example of Christian Speculative Fiction? No, because the scriptwriter(s) — while intelligent about the origin of themes they employ — don’t mean it to be Christian. To say otherwise is to ignore authorial intent.

Of course, these stories are very good, and in fact demonstrates the superior nature of the Christian “myth” and a good story’s basis in this (the closer you get to the ultimate Story, the better your story is). But for these I prefer the term Christ-figure-figure.

Interesting. I haven’t read this series, but that just hits me all wrong and sideways. It’s an exact reversal of the Gospel account of reality, in which man fancies himself the hero and finds that instead he must serve the true Hero. This doesn’t make the story bad, I’m sure, but it does seem to distance it further from the ultimate Christian Speculative Story — the Bible itself.

Just last night I was thinking about this. We were viewing the Star Trek original-series episode “Who Mourns for Adonais?” This is the one in which the crew meets a being claiming to be Apollo, who wields (limited) powers and demands the humans’ worship. Kirk refuses, and at one point says this:

Hey, good for Star Trek, right? Well, as much as I’d like to think so, this brief shout-out for monotheism does nothing to overthrow the whole thrust of the episode: that humankind has a duty only to itself, and has “outgrown” old legends and god-worship, as much as those things have previously benefited our race. “Apollo” in this story is merely a stand-in for any kind of old-style religious deity, who must inevitably (even if slightly tragically) die out and clear the way for man-as-replacement-god.

So while the story nods politely to Judeo-Christian belief, ultimately the story discounts that kind of faith entirely. In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that the second sentence in that quote (“We find the one quite adequate”) was a last-minute addition to the script, perhaps dropped it to soften the blow only somewhat.

(Of course, future and other Star Trek episodes, especially in the Deep Space Nine series, proved that a story, and a realistic universe, can’t survive without something very like “traditional” religion that worships more than simply mankind.)

Izzy, I’m in half-agreement and half-disagreement with your comment:

That last part: absolutely. The first part: I think you didn’t mean to deny that the OT has Christ-figures. They fill the story. Here are a few, directly cited in the New Testament:

Note that all of these are flawed Christ-figures. If they weren’t, people would have had an even harder time anticipating the true Christ, because after all, Moses did a great job all on his own, why couldn’t we have him back again? No — every single Christ-figure left them with some hint of what He would be like, but still with a sense of longing.

In one sense, true; in another sense, not true. Christ has left the Holy Spirit (Acts 1-2), Who of course is as much one God as He is (though a different Person). The Spirit indwells believers, each of whom is a figure of Christ — the literal meaning of Christian.

A Christ-ian, or Christlike one, is a Christ-figure. A “hero” only in the sense that we reflect the true Hero. So I’ve suggested (elsewhere, not here) that our stories uniquely also reflect Christ, though perhaps one degree removed:

As mentioned above: in that case, Christ Himself will do, even if He is never “seen.” Just as I don’t know of any non-Christian storyteller who set out to write a Christian story, so I don’t know of any Christian storyteller who truly wants to craft a “Godless” world.

So, if there are examples in books outside of SpecFic where no Christ figure is present, surely there would also examples inside fiction that is actually speculative.

The post you made before this one helped clarify what you meant by “Christ figure”. When I was talking about “Christ figures”, I was coming from an idea that you were meaning something else. Thanks for clarifying. 🙂

What would you think of a SpecFic that had a God figure, but no Christ figure? How close does it have to be to the original Story in order to be Biblical? For example, in the Narnia books, Aslan acts as atonement for Edmund, but I don’t remember any evidence that the atonement was used as a way of salvation for the other characters. Yet, all of the “good” characters went to the books’ version of “Heaven” in the end. Not the same as it is in real life, but we Narnia fans aren’t really calling it blasphemous or anything. How does that work in other stories? Could there be SpecFic with a God figure, but no Christ figure with a specific sacrifice that serves as an atonement, and still be Christian?

Stephen, I think you’ve done a good job clarifying your definition. The thing is, you’ll find industry professionals, and even some of our regular columnists here at Spec Faith who have a different definition.

In fact, earlier this month over at my own site, I wrote a post about this subject: “Christian Fiction: The Definition Matters.”

My own views are closely aligned with yours, and I’d love to see more Christian worldview fiction, published by Christian, indie, or general market houses.

I do have one area that hasn’t been mentioned yet that I disagree with though. I think the communication of Christian truth can’t be “accidental” and have the work considered Christian. For example, some people looked at Avatar as “Christian” because they saw the hero as incarnational. Uh, no. The possibility was there, but the story took that concept and turned it on its head. The hero instead of coming from glory came from a place of evil, and the place to which he translated was good and pure and spiritual–not exactly parallel to Christ.

In the post I referred to above, I put in a line to my definition that might be impossible to determine, but here it is:

Here is more from that post explaining my position:

Becky

I need to explain better, Stephen. In Mustborn, Sazed loses his faith and rediscovers it, just in time to save the day. His faith is true, and he rediscovers this BEFORE he saves the day.

I think too many books, in showing struggle are TOO dark, TOO violent, or TOO angsty. The rest are perhaps often TOO light. A book that shows the struggle for faith in the midst of hardship, with the right balance, so it doesn’t go to extremes, is something every Christian needs more of. That’s why I call Mistborn Christian Speculative Fiction. It shows someone having faith even when there is no proof. Such emphasis on faith is a Biblical concept in the books.

Heh! I loved how the writers and actors got in fruit past Roddenberry’s militant atheost attempts to preach secularism.

Mistborn, not Mustborn, lol. Shouldn’t use Mobile version to post at places. Blush

Now that I think about it, I think the term “Christian Speculative Fiction” is a phrase, like many others, that can have multiple meanings, all of them just as valid than the others (though in different ways).

Some I can think of are:

The actual genre. Speculative fiction that a Christian purposely writes to be Christian, whether overtly or not. Whether they fail or succeed in this goal determines whether it’s BAD Christian SpecFic or GOOD Christian SpecFic. As someone already pointed out, it doesn’t necessarily change its genre just because it fails to do what it attempted to do.

Speculative fiction that has genuine Christian elements, intended or unintended, including stories written by non-Christians. This definition is different from the previous one as it is not so much a genre as it is an observation on the part of a reader. It may or may not be the sort of thing you put in a Christian bookstore. But it is the sort of thing where a reader might say, “Oh! This is very Christian.”

I think you have a point, Sir. I would say that Narnia is in the first one, and LOTR is in the second. While Tolkien defended the Catholic worldview in his letters of LOTR, he would have probably been apoplectic about any who called LOTR part of a “Christian” genre.

Morgan, yes Ma’am, that irritated me too. I just started with Brooks after years of hearing him trashed (unfairly I think I’ve discovered recently) over Sword of Shannara. But recently, I have started the Word and Void, and the suggestion that it is Christians who are the evil ones to bring about Brooks’ fictional apocalypse. His very UNsubtle jab at those who think their faith is the way to Heaven or disagree with homosexuality, really irritated me. Then I hear that in Legends of Shannara, Brooks has a religious order that is a thinly veiled caricature of Christianity attacking our faith. He pretty much admits this when asked. It really irked me. I’m not going to read his books from the past ten years, that’s for sure.

I love this definition, and its accompanying explanation, in (nearly) every way.

My one thought I’d like to toss into the discussion is that this definition defines a story partly by its author. As has been mentioned, Robert Jordan and Brandon Sanderson’s books couldn’t be included simply because their theology – outside of, not necessarily inside, their books – is unbiblical. For instance, sure, you can probably find evidence of Sanderson’s LDS beliefs in his works, if you dig hard enough; but on the whole the messages and themes of his books are entirely truthful and even Biblical. His works do convey both beauty and truth.

Excluding Jordan and Sanderson for their beliefs opens another can of worms, though: should authors that claim to be Christians but have flawed/heretical theolology – theology flaws that aren’t always obvious in their books – be excluded from this category? Technically, yes. As some have brought up, George MacDonald; or, who comes to mind for me, Brian Davis of Dragons in Our Midst.

It’s a question of which is more important, the author’s intended message, or the message that is actually conveyed? Admittedly, the title Christian Speculative Fiction does include that word Christian. So it may be technically accurate to exclude books written by non-Christian authors. However, I would argue it’s not terribly useful or necessary to do so. What is in my opinion more relevant, important, and applicable is whether or not the message that was actually conveyed reflects Biblical truth, rather than what the author might or might not have intended to convey.

We’d better be careful, or we would end up excluding everyone. We’re probably all heretics to each other. C.S. Lewis was very fond of MacDonald, and although C.S. Lewis was not exactly a modern Evangelical in his doctrine, his writings and even his direct teaching in his nonfiction have encouraged and strengthened many of us in the faith, helping us to form our own beliefs about secondary doctrines. If we include Lewis even though he seemed to think that some non-Christian can be drawn to God by the Holy Spirit while still in false religions, even though he was too mystical and abstract for modern American Evangelical tastes, can we rightfully exclude MacDonald when Lewis would probably have included him, despite the fact that Lewis disagreed with MacDonald’s universalist philosophies? (I just read The Great Divorce, and Lewis directly names and argues against MacDonald’s universalism near the end of that book.)

I strongly agree with the rest of your comment though. Authors don’t have the authority to dictate how readers are to interpret their works. The reader is the final authority on the meaning of fiction, not the author, because it is the reader who is affected through the story and who applies his or her own thoughts and experiences. So, if we Christian readers of speculative fiction find Christian truths in books written by non-Christians, then the truths that we have discovered are really there!

Personally, I think I have to agree with this. I haven’t read Robert Jordan and I’m almost halfway through “Well of Ascension,” so bear with me. While I don’t believe LDS to be a part of Christianity, I think it might be better to to include any story that involves particular Christian themes. Truly Christian themes are universal truths and therefore, while the particulars might be off, in general the exploration of said truths is valid. (Ex: Murder is considered morally wrong on a universal level. But societies disagree on what qualifies as murder.) Personally, on that scale I’d probably include a dozen books, movies, and TV shows that are neither written by Christians nor intended to have a Christian theme or message but have, despite that, a universal truth that cannot be denied.

Now, to fairly go about a truly Christian, orthodox message would involve a much narrower scope involving the bare-bones requirements to actually be Gospel truth. And I’d likely come up with a very, very short list just because there actually is a pretty broad playing philosophical playing field before you hit “not Christian.”

By the by, Ma’am. What do you think of Well of Ascension and Mistborn in general so far? Um, though the ending to Hero of Ages is bittersweet, I warn you, it is not quite as depressing as Well of Ascension is.

I want to say something like C.S. Lewis’s definition of what Narnia is.

A story that reflections how God’s work of redemption would play out in a world that is different from ours in a significant way, including but not limited to the presence of other rational species, different technologies/magic or different choices by mankind.

I said this before, but I can say it again for emphasis, that if a definition is too restrictive, then LOTR itself can not fit into it. If one is going to go by reader interpretation, the idea of “applicability” as Tolkien put it”, or else private correspondence to place something in the realm of “Christian Speculative Fiction” when Tolkien would not, then how do you not use reader interpretation for secular works? Now, if you wish to exclude Tolkien from the list of such books, then that is consistent. Otherwise, you are mining his letters for the “extra push” to define his works in a way he neither presented them, or would have himself termed him. This is, to me, very inconsistent. Use the same looser standards in general, or keep him out. I vote for the looser definition, to open up avenues to more examples of Truth, whether from LOTR or other works.

Now, let me be clear here. I believe that the author’s point of view is the “true” point of view for how something is to be interpreted. But I also think that there is some validity to how the reader wants to do so. So Tolkien, or Jordan, or Sanderson (not a believer like the first two, to be sure) may not consider their work to be in the Christian Speculative Fiction genre, but we can, and that’s perfectly legitimate, as long as we admit also how they thought.

Never ask a lit major something like this.

1. Fiction written from a orthodox Christian worldview, typically by a Christian (but not necessarily).

2. Any story containing Christian elements and themes. (Ex: I would include the pilot of Leverage; Sweet Home Alabama; The Book of Eli; The Lakehouse; some Doctor Who episodes – even if DW is a smorgasboard); and, now that I’m watching it, and despite the rather Buddhist perspective, certain aspects of Avatar: the Last Airbender – I am such a sucker for a redemption story; the Jesse Stone movies; Thor; Tangled; etc.)

And I am now out of this discussion because I am in the middle of “The Well of Ascension” for the first time. Bah humbug on all of you! 😛

A little broad Ma’am, but it works. I thin that while the definition can not be too broad so as to say that EVERYTHING short of Terry Goodkind and so forth are in the genre we discuss, that too narrow a focus leaves out a lot of truth.

Oh, and when you’re done with that trilogy Ma’am, read the novella Alloy of Law. Great stuff.

It’s broad by design, or else there are several authors whose writings simply don’t fit the core, orthodox Christian worldview – and that is not counting a debate on whether or not LDS should count. To take the stricter position is to disclude writings based on any non-Christian POV – and that would include anyone who strays too far on foundational, core Christian beliefs.

I basically offered both definitions , though I should have, as others did, included the third definition of “speculative fiction written from a Christian worldview with a Christian audience in mind”.

I don’t want to discuss the Mistborn Trilogy until I’ve read all three, so I’m sort of avoiding those questions for the time being. It’s all one story, for me, rather than three. Thanks, though, I’ll put Alloy of Law on the list.

I have read all of the comments up to this and I totally agree with you Bethany. More success !

This is a tough nut to crack, and I often wonder if it’s even possible to craft a definition that’s truly satisfactory. The outcomes always seem either too restrictive, too permissive, or too convoluted. We’re also compelled to make exceptions to include our personal favorites or exclude stories we dislike.

I think Stephen’s definition, in its current form, is too convoluted, though it does a great job of putting all the pieces on the board. It loses utility with every additional sentence and explanatory sub-paragraph. This definition needs to be concise.

Becky introduces the quality of intent or “purposefulness,” that is, a Christian story is meant by the author, from its inception, to be a Christian story. I agree that when you set out to write a Christian story, that’s probably what you’ll get. However, without an explicit declaration from the author, it’s hard to prove or disprove intent. Did the author really mean to say that? Did he mean it enough?

Then we have the problem of orthodoxy, and who defines it. Kaci refined Izzy’s criteria into a pretty concise package:

1. Fiction written from a orthodox Christian worldview, typically by a Christian (but not necessarily).

2. Any story containing Christian elements and themes.

I think point 1 encompasses intent, while making room for those of us who sometimes find our Christian worldview (or divine inspiration) taking charge even when we’re not trying to write a “Christian” story. However, as others have noted, it’s also possible to intend to write a Christian story but be so burdened with misapprehensions about Christianity and/or Christians that the final product doesn’t reflect a Christian worldview. Assessments of orthodoxy can be problematical. As Bainespal observed, one man’s orthodoxy may be another man’s heresy, and it can be hard to identify objective truth on some questions. Even in this little forum, we’ve already expressed differing levels of tolerance for doctrinal eccentricity. So, I think we still have the problem of adequately defining what we mean by “Christian worldview.”

Point 2 is too permissive for the purposes of definition, but I think it identifies exactly what we cover here at SF. We find the Christian elements and themes that are strewn across the spectrum of speculative fiction, intentionally or not, and talk about them. We don’t limit our discussions to “Christian spec-fic,” however we define it.

Timothy: I said this before, but I can say it again for emphasis, that if a definition is too restrictive, then LOTR itself can not fit into it.

I think that’s a good rule of thumb. I hereby dub this the Stone Limit for Christian Speculative Fiction, and add to it, the Warren Limit:

If a definition is too permissive, His Dark Materials will fit into it. This is a set of stories with an intentionally anti-Christian worldview explicitly affirmed by the author.

From Kaci:

Hey, I asked. And now I suggest that absolutely, a Christian speculative story must be written by a professing Christian. To say otherwise seems to yield an overly broad definition, and seems to say that either a story is “Christian” or anti-Christian.

There’s a third category, in between the two, which I would call redemptive story or Judeo-Christian story. (This term is similar to the adequate description of America, not as a “Christian country” or a “secular country,” that is, founded on either of those worldviews, but a country founded on “Judeo-Christian” beliefs.)

We don’t need to say a story is specifically “Christian” in order for it to be redemptive. Source: Paul’s famous citation of Greek poetry in Acts 17. He found redemptive value in it — because “all truth is God’s truth,” and all beauty His also — but it wasn’t Christian.

I’m not familiar with many of those, only Doctor Who, Avatar: The Last Airbender, Thor and Tangled. In my view, those would fit under the blurred-edges “category” of redemptive or Judeo-Christian storytelling. Yes, the very structure of a story itself is Christian, as our world is a “Christian” or God-reflecting world. But for a non-Christian storyteller who uses Christian themes, I would suggest those Christian elements are copies of copies — one more degree removed from the Original. Of course, it can be argued that a skillful copy of a copy could be more glorifying to the Creator, than a half-done copy by someone who is personally closer to Him. (That’s another topic.)

Though I wasn’t trying to come up with a complete definition (or a simple one, as Fred noted), I do think this one allows for Christians who write stories that don’t seem Christian. For the skillful Christian author, this is never really true. Any time a Christian writes a story, and is not actively trying against writing it from a Christian worldview (and why would he/she want to do that?) his/her story is a Christian story.

This includes someone like Tolkien, whose world runs on Biblical “rules” and simply can’t help but reflect themes of the Epic Story: heroism, sacrifice, good vs. evil.

But, unless I’ve missed something above, I wonder which authors would seem to be ruled out. Again, I suppose I am suggesting that “Christian speculative fiction” should be limited to Christian authors. Otherwise, while some Christians ignore the reality of common-grace truth-echoes in the world, this says the nonbeliever’s understanding of Biblical themes can be superior to a believer’s, and ultimately that cannot be the case.

I’ve never thought a division like that is necessary. Here’s why — because while Christians and non-Christians have different G/gods, and we have different sources of ultimate authority (Himself vs. ourselves), we do share two thing: this world and the world of story. Nonbelievers are already playing according to God’s rules in creation and story sub-creation. It’s a touchpoint, and a bit of a cheat (for the Christian!). Thus, the Christian author can write for both, and if he is a good one, all will be drawn in.

From Fred:

I agree, brother; that’s why this is a work in progress, and mainly a conversation-starter. Plus, someone else — likely one of those Yuppie Calvinist Doctrine and Literature Wonks out there — likely has a better definition. I just haven’t seen it yet.

That’s where the debate veers into strictly nonfiction territory. I would argue that Scripture defines the basic Christian worldview, for plenty of wiggle room on the “nonessential issues” (end times, baptism, how often to have Communion, and such). Yet it leaves no wiggle room on “mere Christianity” — God’s nature, His “plot” of the Gospel, man’s nature and his responsibility and fate, and the future of our world.

Statements of faith are helpful. Ours certainly isn’t the first. But every Speculative Faith regular columnist subscribes to this one, and I’m sure we would all stand firm on it and say, I hope lovingly, We believe this reflects the basic Christian worldview. Here’s why.

There are plenty of Christian speculative stories that contain material I personally find fault with. For instance, I now basically disagree with the entire end-times premise of the Left Behind series. (And please, never tell my 16-year-old self I actually said that.) I also disagree with some of the God-can’t-move-unless-you-pray implications of the earlier Frank Peretti novels. Do I go “heresy”-hunting against them? Sure, but I come back with no game, because neither of those beliefs are “heresy.” They’re within orthodoxy. So I rejoice in the truths those authors portrayed, and by no means count them as less than Christian. I’m also grateful for how God used those novels in my life.

Ultimately, that motion would hold that any Christian Speculative Story definition can’t say or imply “the story must repeat the explicit Gospel, sufficient to get someone saved if they Repeated the Prayer.” I second the motion. All in favor?

Agreed. While Pullman, like anyone, is working with Christian “materials” (pun unintended) from this world, his intentions are clear and it would be foolish — not to mention contrary to the consistent Christian’s reading hermeneutic — to ignore them.

That brings me to the Burnett Limit, which I think may combine both:

Think about it. If we say “a Christian speculative story must somehow repeat the whole Gospel,” then we need to toss out, at bare minimum the Psalms. After all, they only talk about how much the authors love God’s Law (law! ugh! we’re about grace now!) and even have those dreaded Imprecatory Prayers that, supposedly, ignore what Jesus said about loving our enemies. And what of Esther, which doesn’t even mention God’s Name? What of the book of Ecclesiastes, which explores the natural results of humanistic worldviews? What of Jesus’s parables which remain “unexplained”?

Clearly we need another definition, and not one that merely applies consistently to Scripture, but one that is itself formed by Scripture as the Axiomatic Prime Story.

I see your point Stephen, but here is my point, for clarification. If there is any misunderstanding, it is my fault, so I will attempt to do better. Is Christian speculative fiction include stories seemingly against the author’s will, or that he himself would not have included? Because to include LOTR in that genre, you specifically have to say that Tolkien meant it in a way that he explicitly did not.

Now, Tolkien and Lewis both placed great value on reader interpretation. Lewis himself both criticized those who stick too closely and unerringly to an author’s position. Yet he also criticized those who tried to say that an author means something he does not. Giving your own opinion, while admitting the author’s point of view seemed to be his solution.

I guess what I am saying is that we are saying that since Tolkien was a Christian, it was okay to categorize his work in a way that is expressly against his intent, while for those who are not Christians (Sanderson) or Christians who wrote “secular” fantasy (Jordan) but both showed Scriptural truths, that we’ll leave them alone. I just can’t wrap my mind around how this isn’t problematic and doesn’t amount to just saying that we like Tolkien as a classic, so let’s “grandfather” him in.

I also think that this does restrict us from many examples of Truth that we can find in other works. And that seems to be against the point of discussing these ideas of Christian speculative fiction, or Christian ideas in fiction period, if we exclude works right off the bat.

Sir, to answer your question and also refer to Stephen’s “common-grace” example, I would say that it is easier to differentiate than first appears. Two authors off the top of my head, Pullman and Terry Goodkind for instance, may have truths embedded therein at some points, but they clearly are critical and even hateful of Christianity and Christians. They are clearly not anywhere near Christian in scope.

It was a bit broad, I know, but I don’t know how else we could actually include things like Ender’s Game and Mistborn, or anything that’s unorthodox but not necessarily heretical. In fact…

This is actually more in line with where I was going with my second definition.

Yeah, which is why I tried to boil that statement down to bare, bare bones. My personal “unorthodox but Christian” category is pretty big, to be honest, and I’m much more lenient with fiction, all in the name of exploration.

This sort of goes back to my treacherous little second definition. How does it eliminate the “a-Christian” category?

Keep in mind, guys, I said “Christian themes.” I didn’t say “Christian fiction.” Leverage is not a Christian show. However, in the pilot Nathan Ford offers the others a chance at a new life and the means to carry out that new life. He facilitates, he leads, and they follow his principles. Nathan himself is a bit of an unredeemed hero; and season three deals strongly with penance, repentance, and redemption through Eliot. Thor is not a Christian show, but, well, you wrote that series. (I stretched it with Avatar; and in all fairness we’re stretching it with Doctor Who, too.) Sweet Home Alabama is about reconciling a marriage – which is why I like it. Those are not Christian stories, but they do possess Christian elements.

Then, by rights, we have to disclude anyone unorthodox or simply not Christian – including beloved Mormon authors and eccentric, borderline heretical supposedly Christian authors. This takes Ender’s Game, Mistborn, DW, Thor, and the Avengers off the table.

Anyway, how does it suggest a non-believer’s understanding to be superior or inferior? A justice-themed book is a justice-themed book. A book praising the sanctity of human life is a book praising the sanctity of human life.

(Aside: I really need to stop going out of order.)

I’m not offering my short list. However, let me put it to you this way: Who’s understanding of universal truth is more consistent with Scripture (and remember I have not read the former): The Shack or Ender’s Game? Young is a professing believer. Card is a Mormon. The Shack or Doctor Who? The Shack or Thor?

Believers have the Spirit inside them. That doesn’t mean we automatically have cosmic understanding and comprehend the depths of divine wisdom. So yeah, there’s plenty we do not understand without the Spirit’s help. But sometimes, maybe sometimes, Gentiles are a law unto themselves.

It’s one I heard once. But I have to say that while, yes, of course you can write for both, but most people seem to be naturally bent toward one or the other.

Stephen,

I didn’t intend to ding you for writing a complex definition, particularly as a first draft–it was an example at hand of one of the three problems we invariably fall into when we try to do this. It may very well be that there’s no definition that is both concise and complete.

From your reply to Kaci: And now I suggest that absolutely, a Christian speculative story must be written by a professing Christian.

Ah, this is a change from the original formulation, which didn’t demand a Christian author. So this is an essential, but not sufficient condition. That is, “Christian fiction must be written by a Christian, but a Christian author does not necessarily imply a Christian story.“

Any time a Christian writes a story, and is not actively trying against writing it from a Christian worldview (and why would he/she want to do that?) his/her story is a Christian story.

Arguably, then, the Harry Potter books are Christian stories. ducks for cover

From your reply to me:

I would argue that Scripture defines the basic Christian worldview…

Yes, but I think if we’re trying to build a definition here, we have to go beyond “Just look in the Book.” Statements of Faith make things a little clearer, but I’d propose that’s still not enough–a worldview describes how we apply those beliefs as we interpret the world around us. Yes, your bullet points beneath the initial definition do touch on this.

Any definition of Christian Speculative Story cannot rule out Scripture itself, or any book, chapter, verse or portion of the Bible.

Hmm. We’ve been trying to define Christian speculative fiction, and while Scripture contains the truth that should underlie all Christian fiction, it’s neither fiction, nor speculative. It’s probably reaching too far to demand that a definition of Christian spec-fic be applicable to the Bible itself. We certainly couldn’t include stories that repudiate Scripture (which I think is what you mean here), and I’ve not yet seen a proposed definition that would.

(Hurrah. I get to write me first comment with the new comment arrangement.)

From Fred:

I think the confusion results from my vague phrase here:

The key word there being clearly. In other words, the story doesn’t need to “out” the author’s faith to be considered Christian. However, can we say a secular writer’s story is just as Christian as a Christian author’s (even if the secular writer’s story is better-done or even shows truth more clearly)? I’m not sure. In some cases, a secular writer — perhaps without knowing it — reflects God and even the Gospel more clearly in the story, perhaps because of his or her greater creative skills.

Naturally there’s a lot of uncertainty here, but that’s what makes it fun, eh wot?

It seems here we’re working with three sets of “ranges,” with blurred edges, with subset characteristics. Let’s see if these help, even if it seems a bit mathematical.

1. Christian speculative stories

2. Redemptive or Judeo-Christian speculative stories

3. Anti-Christian speculative stories

Though surely there is some overlap, this might help define things better. Thoughts?

I’m not seeing the discussion–hope it hasn’t been lost in the make-over.

I just wanted to say, I understand now why we had the responses Monday to what books belong on the influential and on the best lists of Christian fiction. Clearly we have varying definitions, so our lists include a wide variety, too.

I think the given should be that professing Christians write Christian fiction. Whether we believe the stories must have redemptive scenes, a Christian worldview, or Christian themes, none of that is truly possible if the story isn’t written by professing Christians.

I understand and agree that I as a believer can read general fiction and find parallels with a Biblical worldview, but it is a lack of discernment, I suggest, to turn around and label those stories as Christian. The truth is, there will be much of those stories that is NOT Christian because the world does not believe what Christians believe.

I’m uncomfortable with the Judeo-Christian aspect of this discussion–wish I had it in front of me. That term is really a replacement for certain moral values. Jews do not believe in Jesus Christ (no news flash there, I realize 😉 ), and therefore fiction that would appropriately fit under a “Jewish beliefs” heading cannot be considered Christian. Moral, yes. And I think there is a definite place for and need of stories with Judeo-Christian underpinnings. But when it comes to definitions, those books are not the same as Christian fiction.

The point is, Christian is a divisive term. It sets apart that which adheres to the teachings of Jesus Christ. One way or the other, Christian fiction must reflect Jesus. Otherwise we might as well agree to the term religious fiction or universalist fiction or moral fiction. Judeo-Christian fiction is right there with those terms, I believe.

Becky

I’m with you, which is why thought I brought up that term (borrowed from the references to the U.S. as a “Judeo-Christian country”), I prefer using “redemptive” or “general redemptive” fiction. Compared with specifically Christian fiction, general redemptive fiction could be compared to the added testimony of nature (Romans 1) to the central, sure testimony of God’s Word.

Or: general redemptive stories are the echoes, Christian stories — especially starting with The Story, the Bible — the source.

Non-Christian storytellers must inevitably borrow “Christian materials,” such as truthful and redemptive themes, and beauty in skill, to make their stories any kind of success. That does not mean, however, that they are as “Christian” as a Christian novelist’s work. And that doesn’t mean such stories have little value, or may even be better done than a Christian story — just as a truly Christian engineer may not be as good as a “secular” engineer who does better work.

As for which author, or engineer, gives God more glory, though — as if either one is in a competition to give God more “glory points” — I’m not sure I even want to tackle that. Let Him decide.

I personally don’t see the problem with the term “Judeo-Christian”. Obviously, Jews are not Christians, as any who don’t accept Christ’s free gift of salvation are not. However, it is a good thing to acknowledge that the NT is not contradictory with the OT and instead forms one complete whole and narrative with it. To acknowledge that Christianity was from Judaism, as the fulfillment of the prophecies in that faith is fine with me. It also helps associate instead of pit them against each other, and thus combats the heresy of “replacement theology” so-called.

In my earlier comment, I wish I’d said that. Original Judaism finds its fulfillment (not its expiration or replacement) in Christ. Though one could do a word study on the term “Judeo-Christian,” my intention in using it was to refer to Jewish/Christian common morality, and perhaps also the redemptive themes and grace prophesied and typified in the Old Testament, and fulfilled in Christ in the New Testament.

Yeah, I have to agree I don’t really see much problem with “Judeo-Christian worldview,” either. It’s referring to a set of ethics, mores, culture, and underlying principles that came to shape what we call “Western Civilization.” It really doesn’t have much to do with actual religion, in that sense, being more philosophical by nature (and allowing for things such as deism, theistic evolution, intelligent design, and everything that came out of the Enlightenment, if my memory serves). You know, nevermind that, technically, both Christianity & Judaism originated in the Middle East, not Europe (okay, so it bugs me people call them Western religions).

Timothy, Stephen, I hadn’t thought of Judeo-Christian in terms of keeping perspective of the OT-NT bridge, but yeah. Things do get a little complicated, in some respects, in that originally Christianity was merely considered a cult version of Judaism who believed their Messiah had already come. The more Gentile it became, the less the Jewish association had as much influence. (We’re now horribly off-topic, but hey.) We sort of forgot it was Jews who first preached the Gospel for awhile, and, thankfully, efforts are being made to correct that.

Ultimately, though, I think that Scripture itself teaches that throughout history it’s never been so cut and dried as either Jew or Gentile liked/s to think. I mean, there were no Jews, officially, until Mount Sinai. In both ends of Scripture, you have both Jews and Gentiles called either ‘righteous’ or ‘wicked.’

Okay, sorry. I’m a bit of a harpy about the continuity of Scripture. Don’t ask me why. Anyway, I find the term “Judeo-Christian” helpful in distinguishing “normative Christianity” or “non-believers with good values and/or theology/philosophy/ethics” from “Christianity” – especially when living in a culture where everyone slaps “Christian” around the same way they use “Kleenex” or “Coke” regardless of the actual brand of tissue or soft drink.

I think I’m looking at this a bit differently. If the Christian worldview is the sole and absolute universal truth, then every jot and tiddle of truth is Christian. I’ll say “God’s truth” just to keep it simple. So, if a non-Christian speaks truth, he speaks God’s truth – and therefore Christian truth – regardless of his salvation status.

Stephen, I’m retracting my former statement on Avatar. It’s got a lot of great moments (I’m a Zuko fan, btw – sucker for a redemption arc), but the Buddhism come so much into play that my suspicions were confirmed that I was stretching a bit far. (I absolutely love how they settled the “I can’t take a life” conflict. That’s probably the most natural way of tackling that subject without making the character go against his own values that I’ve seen. I didn’t feel cheated at all, which was brilliant. But how the heck was this ever a kids’ show?)

Back to Becky – and sorry for the intrusion: This really kind of is where the “Judeo-Christian” phrase is helpful. It understands that, philosophically, the themes align with Scripture (or, at least, come close to doing so) while acknowledging they may or may not be, in fact, Christians.

Ironically enough, I’d be fine with a generic “religious” category in which anything from an obviously religious bent might fall. Course, for whatever reason, some bookstores who shall remain nameless to protect the guilty tend to have “religious” and “Christian” – which is weird to me. And most of the obviously religious fiction I can think of that isn’t Christian is some version of Hinduism, Buddhism, Mormonism, or secular humanism (yes, I count that). I just kinda think the implications would still be that people would mostly avoid anything that wasn’t their religious subcategory.

[…] Define ‘Christian Speculative Story’. […]

Stephen,

Thanks for this article.

I needed to read a basic definition of Christian Speculative Fiction and your definition helped.

I link this article to my blog.

Marion

Stephen,

I have a question for you.

Can a Christian Novel just be entertaining? Is that possible?

It seems we are trying to nail the down a definition and message….that we are forgetting that stories should be entertaining.

“Behold, what I have seen to be good and fitting is to eat and drink and find enjoyment in all the toil with which one toils under the sun the few days of his life that God has given him, for this is his lot.” {Ecclesiastes 5:18 ESV}

I wrote that scripture to show that God’s word mentions having enjoyment and it seems in our modern Evangelical culture that gets dismissed or overlooked.

And as Christian Fiction is growing into becoming a viable genre….it seems everyone wants to have this great meaning, but entertainment and enjoyment gets left behind like 8-track players.

I’m just wondering if anybody else feels this way?

Of course, a good story should have meaning and depth. However, I believe it should be entertaining and enjoyable to read first and foremost. Let’s not leave that out of this definition for a “Christian Speculative Story.”

Marion

Yeah, I think that ties in with the OT where God said he wanted them to make the priests’ robes a certain way “for glory and beauty.” In other words, it was attractive and dignifying, so why not?

If a story contains truth and is beautiful, then why do we care to define it as “Christiantm” or “non-Christiantm?” If something is true, why should we care about its origin? As it says on the SF Statement of Faith,”We believe God can and does let His truth be echoed in His creation, for all truth is His truth and remains so even if it is found in a story that does not specifically credit Him. Still, we believe the Bible is the only inspired, infallible, and authoritative Word of God, and our only sure source for knowing Who God is, what the Gospel is, and what we must do in response.”

Why?

My thinking is that we refer to it as specifically Christian to recognize that the Christian faith is the only source of truth – being based, as it is, on the Scriptures.

Also, a Christian book would inevitably point us toward the Lord in some way, whereas any story can contain generic truth without doing that (i.e. it might portray to us that everyone is flawed, which is true, but that is a long way from saying that we are all sinners and in need of Christ).

Thoughts, anyone?

[…] May 28 question, Which [Christian Speculative Books] Are Required Reading? and my May 30 followup Define ‘Christian Speculative Story.’ Because, it turns out, not only is L’Engle’s debut yet beloved classic fantasy boring to me (at […]

Thanks for doing this.

Is there no room for non-human intelligent beings in Christian speculative stories?

I have also attempted to define, or at least describe, Christian literature, primarily fantastic, here: http://sunandshield.blogspot.com/2011/02/describing-christian-novels.html

C.S. Lewis was pointed to Christ by the myth of Baldur’s death and resurrection. Most modern fantasy stories contain a surprising amount “Christian” elements.