How Do the Fishmen and Pirates of ‘One Piece’ Subvert Systemic Racism?

Ten thousand feet below the surface of the sea, trouble is brewing. Ancient racial hatred is simmering, growing dangerously close to boiling over.

This is the situation in the Fishman Island Arc of the long-running anime/manga One Piece when the main characters, the Straw Hat Pirates, arrive at Fishman Island. In the midst of the action and humor of this pirate adventure story, author Eiichiro Oda gives us an unexpectedly insightful glimpse into racism and its effects upon a culture.

Readers, ye be warned: there be spoilers throughout.

Fishman Island, deep beneath the ocean, is inhabited by a race of undersea beings who are both stronger and more-varied than humans. Some are beautiful, such as mermaids. Others are huge and powerful, like shark-men or octopus-men, massive creatures who can crush a human with a single blow. The loveliness of the first and the fearsome destructiveness of the second have made the fishmen into hot commodities at the slave markets of Sabaody.

Pirates often descend to their home island, deep under the sea, in order to kidnap fishmen and their children. Fishmen pirates return the favor, terrorizing humans and destroying their towns. This clash of races has been going on for generations.

In the midst of this racial animosity, two inhabitants of Fishman Island saw the toll it was taking on their society and vowed to make a change. They both saw the same suffering. Their reaction, however, could not have been more different.

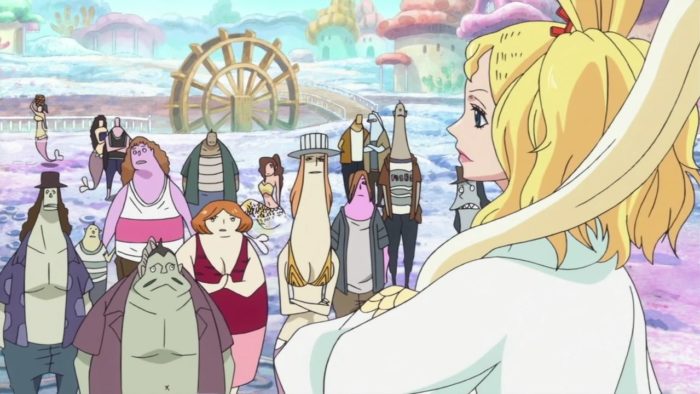

The Mugiwara (Straw Hat) Pirates of One Piece, with friends from Fishman Island.

Otohime’s quest for harmony

The first fishman to attempt to change their situation was the queen of Fishman Island. Queen Otohime was a goldfish mermaid, a very beautiful and delicate creature. Her heart was filled with love for her people. She particularly loved the children of her country.

As she looked around her, she saw the tremendous hatred of her people toward the humans and visa versa. She could not bear to think that this hatred would be passed on to the innocent next generation. Despite her delicate state, she determined she must find some way to improve her people’s situation.

Otohime became convinced that what kept the humans and the fishmen apart was distance. Humans lived on land. Fishmen lived ten thousand feet beneath the sea. Humans seldom saw fishmen, unless they were either attackers or slaves. Fishmen seldom saw humans, unless it was pirates who came to raid them and capture slaves. Otohime thought that if the fishmen, who could breathe both air and water, were to move to an island on the surface of the sea, the two races might come to know each other and their old hatreds could be put to rest.

Otohime became convinced that what kept the humans and the fishmen apart was distance. Humans lived on land. Fishmen lived ten thousand feet beneath the sea. Humans seldom saw fishmen, unless they were either attackers or slaves. Fishmen seldom saw humans, unless it was pirates who came to raid them and capture slaves. Otohime thought that if the fishmen, who could breathe both air and water, were to move to an island on the surface of the sea, the two races might come to know each other and their old hatreds could be put to rest.

To do this, however, she needed to convince her people to move. Specifically, she needed to bring a petition to the World Government that demonstrated that a majority of her people agreed and would be willing to relocate.

To this end, the beautiful queen traveled far and wide across Fishman Island, giving speeches and asking for signatures for her petition. Everyone loved Queen Otohime. She was beautiful and kind. Their love for her, however, was not as strong as their hatred of the humans. They did not want to go live among them.

For years, Otohime moved among her people, pleading with them to think of their children, their next generation, and to make a change, but almost no one would sign her petition.

They were embarrassed. They looked away.

In many stories, a beautiful, well-loved queen would be instantly persuasive. Otohime’s experience in the Fishman Island Arc, however, is not so different from that of the real early abolitionists here in America. By the time of the Civil War, many in the North wanted to end slavery, but it was not always the case. Originally, abolitionists were a fringe group, as looked down upon as any fringe cause today. Like those real abolitionists, who persevered until more people grasped the importance of their cause, Otohime did not give up.

Through a mixture of courage and luck, Otohime was eventually able to reach her people. Suddenly, many were willing to sign the petition.

Then tragedy struck.

Queen Otohime was shot and killed.

When the dead body of the murderer was dragged before the people, it was a human.

Hordy’s journey of hatred

With Otohime’s death at the hands of a hated human, all effort to get her petition signed was forgotten. Instead, hatred of humans grew.

Enter Hordy Jones, a young great white shark man who is the leader of a gang. Hordy, too, looked at the hatred and violence between the humans and the fishmen and hated what he saw, but his reaction was the opposite of Otohime’s.

He wanted to conquer and enslave the humans. He felt that the greater strength and speed of the fishmen, and the fact that they could breathe both air and water, made them the natural superiors.

Like Otohime, Hordy meets with resistance. Fishmen may hate humans, but they don’t necessarily want to conquer them. The reaction of Hordy and his gang was to turn their anger against their fellow fishmen.

Hordy and his gang set out to conquer Fishman Island, as their first step toward conquering the world. While they claim it is the humans they hate, it is their own people whom they are terrorizing and harming. A stolen drug makes them stronger than their fellows, and they begin to do great damage to the island.

In the midst of this struggle, Otohime’s son, the prince, comes face to face with Hordy and learns of Hordy’s past. What he learns horrifies him.

In One Piece, there are a number of fishmen who have been truly harmed by humans.

Hordy Jones is not one of them.

“Take over the resentment. Okay, Hordy?”

Hordy was never a slave. He never suffered at the hands of a human. Instead, Hordy adopted attitudes of others around him. Hordy hated humans because he saw humans hating his people, and his people hating the humans back.

He was exactly what Otohime had most feared—a child who had bought into the grudge of his elders.

Hordy went on to say that he thought Otohime’s methods were making the fishmen weak. He needed the fishmen to hate humans so that they could destroy the humans—which is why he believed Otohime had to die.

Otohime had not been shot by a human after all.

It was Hordy who killed her.

With the help of our heroes, the Straw Hat Pirates, Hordy and his gang are defeated. All across Fishman Island, fishmen, who are grateful that Hordy was defeated, sign petitions to fulfill Otohime’s dream.

The future of the fishmen

One of the fascinating things about the Fishman Island Arc is that in the 900-plus episodes of One Piece, we are shown fishmen who truly suffered at the hands of humans: but Otohime and Hordy were not among them. They did not themselves face great prejudice. Instead, they were presented with a world that already held such prejudice, and they had to decide whether to accept it.

Captain Hordy Jones with The New Fishman Pirates.

Hordy chose to continue the heritage of hatred and violence. He was not a victim. He voluntarily embraced a heritage of violence. Otohime, on the other hand, chose not to accept it but to stand up to it. Her choice was not a popular one, but she refused to be daunted. Yet Hordy’s position is stronger than it might first seem. Even if Otohime’s vision is realized, will it really help? Will fishmen and humans ever learn to live together?

Can such terrible hatred and prejudice ever be overcome?

Perhaps, not, because it is very difficult to lay aside prejudice.

Or, perhaps so.

Because difficult as it may be, people can change their minds.

In fact, in the course of One Piece itself, we, the audience, have been led to change our own minds about the nature of fishmen.

Back when all fishmen were evil

The Straw Hat Pirates did not meet their first fishmen at Fishman Island, or even at the slave markets of Sabaody. They met them much, much earlier.

The Fishman Island Arc covers episodes 523 to 574 of this long-running series, but the first fishman appeared in episode 31. Arlong was a brutal sharkman who terrorized a village of innocent, defenseless humans. For years, he and his crew of fishmen pirates rob them, destroy their houses, and, upon one occasion, presented a young mother with the choice of disavowing her adopted children or facing death. When she would not desert her children, Arlong murdered her in front of her two little girls.

One of those girls grew up to be the navigator for the Straw Hat Pirates.

Nami, our navigator, started the series hating all fishmen. As the story continued, however, and she learned of the plight of the fishmen at their home island, Nami—and the audience along with her—began to see fishmen less as made in the image of Arlong and more as individuals in their own right.

It was not fishmen who murdered her mother and enslaved her town; it was Arlong. Other fishmen did not deserve to suffer for his crimes.

As Nami’s understanding of fishmen changed, so did the audience’s. We learned that fishmen were not brutes. They were people like us: some good, some bad.

At the conclusion of One Piece‘s Fishman Island arc, fishman Jinbei donates blood to save his friend (and future pirate captain) Luffy. During a montage of violent moments from One Piece‘s hundreds of episodes, a narrator solemnly observes, “If you hurt somebody, or if somebody hurts you, the same red blood will be shed.”

Otohime’s vision: a world of shared blood

This process—looking beyond the exterior characteristics to see the individual—is exactly what Otohime hoped for. She hoped that by spending more time among each other, humans and fishmen might start seeing each other as individual beings.

We ourselves will never see a fishman or a giant, but we live in a world that is not so different from that of Otohime and Hordy. Around us, we see people who have been the direct victims of racism, but there are many more—especially children—who have not suffered directly but who see all around them the hatred expressed by others. To this end, each of us must ask ourselves a question:

Will we choose to follow the path of Otohime?

Or of Hordy?

The Fishmen and humans of One Piece have a long way to go, but one girl, Nami, has laid aside her hatred, and one inhabitant of Fishman Island, Otohime, has opened the way towards a more harmonious future.

May our choices be as wise and as brave.

I haven’t seen One Piece, but I’m glad they have such a good discussion of racism and prejudice in the show.

One thing that the next generation of storytellers might need to tackle is impatience, fatigue and how well peaceful messages are received by those that feel like they’ve waited long enough for their suffering to end. Some people might not accept a message like One Piece’s and feel justified in continuing violence because they don’t feel like a peaceful resolution is possible. Either that or they might feel like it’ll take too long. So maybe that will need to be the next step for some writers, showing how a violent and hateful approach actually slows down progress and isn’t usually justified.

This article just talked about this issue, but One Piece is an amazing show. The story is light and fun with action and adventure, and these issues are merely part of the world. This strangely makes the point a lot stronger, I think, because it isn’t preaching, isn’t in your face, and, therefore, feels entirely fresh.

And the subject isn’t over. The problem is still going on in the background…as of episode 920.