Rearranging Icons: An Introduction

A few months ago, Stephen and I wandered into a conversation about the meaning of icons in literature and their connection to Christian faith, and we agreed it was a topic worth examining in more detail in a feature here at Speculative Faith.

After some head-scratching about how to approach this task and divide the labor, we decided to simply continue our conversation via e-mail and post the discussion here in several parts with some notes to provide context. This way, we hope, it will feel more like a chat between friends rather than a series of lectures or essays.

So today, we come in shortly after the conversation started, when we were hashing out the details and talking about definitions. We’re both busy guys, so you’ll see there are some gaps in these exchanges, but the great thing about written correspondence like this is that the conversation “keeps” until one or both of us has the opportunity to give it our full attention.

Please feel free to enter and expand the discussion in comments to these posts.

To keep things straight, we’ll show my comments in blue, Stephen’s in green, and notes external to the conversation in black.

February 15, 2012

Stephen,

Sure, I’m still up for the icons series. I guess the big question is how we want to plot this out and divide the labor. Piggybacking on your thoughts, we’ll probably need a brief introduction, definitions and history (which might be two separate posts), examples from spec fic, and maybe a discussion of how icons can help or hinder our understanding and storytelling, depending on how they’re used. Then, a brief conclusion to summarize and wrap up. We could do the posts collaboratively, with a single voice, or tag-team either within or between posts.

Another alternative might be to just continue our conversation here in a less structured way via e-mail and post that after a bit of editing, with some framing comments. Hmm…that could even kick off a recurring feature where pairs of us go back and forth discussing some issue over a few weeks on e-mail, then post the conversation in one or more parts, as necessary. “Becky and Stephen Talk Tolkien,” or somesuch.

Getting back to icons, definitions are going to be critical, and I think it will be important to explain both what an icon is, and what it isn’t. Perhaps the biggest distinction is that icons communicate fundamental, enduring truths and encapsulate them in a compact form we understand intuitively. The Firefox icon, to use a mundane example, carries a lot of information wordlessly and represents a very complex piece of software. A stereotype or caricature, on the other hand, perpetuates misunderstanding and untruth. There are also branches to the concept. A character or object can become “iconic” in the sense that it serves in our mind as an exemplar of what such a person or thing is or should be, and a window into what it really means.

Fred

———–

March 15, 2012

Fred,

Good gravy. It’s been exactly a month since your message. Please forgive my delay. And I hope this message finds you and yours doing well!

A few quick thoughts:

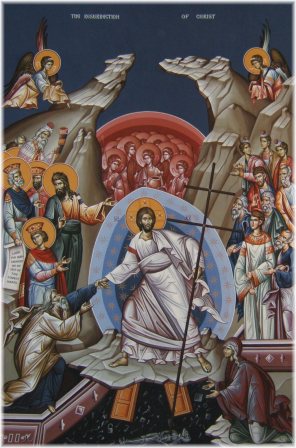

Might we start this next month, earlier in the month — to include the concept of Easter / Resurrection Sunday, the culmination of the only perfect icon and person, Christ Himself?

I love the idea of trading emails back and forth. I’ve done that at least once before and the results made for a great read. For that to work, though, and not to frustrate you, I’ll need to make sure to commit, now, to one email per week, sent your direction. End of project? When it ends, I guess.

Starting out with definitions and history sounds like a great idea. In fact, it seems you’ve already begun with the definitions. I’d love to follow up with the history, both summaries of “icons” in Scripture — the construction of the Tabernacle, especially — and in church history. A future column or two could explore how Christians in the Reformation began hating on icons, and the dangers they did pose then and do pose now … but also expand into Biblical balance.

Over and out, and Godspeed, brother,

Stephen

——–

March 15, 2012

I like this format…should be interesting. I’ve read some things about it by Madeline L’Engle in Walking on Water.

What did L’Engle have to say about them, I wonder, Galadriel?

I believe she has a Catholic background, correct? If so, she would indeed be more comfortable with icons — either used correctly, or used otherwise.

Protestants may get away with icon worship by a neat little trick: by not calling them icons. See, instead we call them Role Models.

Example: Tim Tebow. Some rare Christian sorts may “iconicize” him. Then other Christians, forgetting that Tebow may actually be awesome and that any rare folks’ iconicization is not his fault, blast the wrong supposed motives. And around and around we go, missing what really leads to idolatry and other sins: not the things or people who are idolized or “iconicized,” but the sinner’s own sinful heart.

Meanwhile, I greatly anticipate more of this series. I’ll have part 2 this Thursday.

Madeleine L’Engle was an Episcopalian.

Aha. And that is why I need actually to read her books. Thanks for the fact-check!