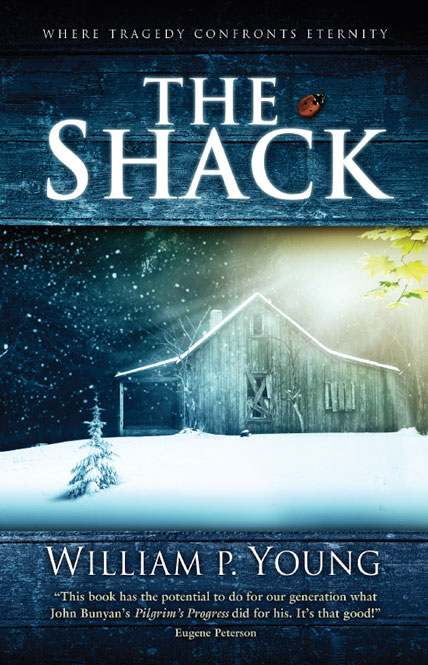

Six Lies Christians Believe About ‘The Shack’

This week I finished The Shack book. For ten years Christians have debated The Shack. Now that William Paul Young’s book has been adapted into a movie, starring Sam Worthington and Octavia Spencer, we’re resurrecting The Shack book debate all over again.

Some fans praise The Shack as worthy fantastical fiction that honestly explores evil and suffering, and the loving nature of God with metaphors and literary devices. Critics say the book distorts God’s character and biblical truth, while at best flirting with false teaching or heresy.1

Now I’m exploring this popular book, not just as a Christian who loves truth and doctrine, or a Christian who prefers fantastical stories, but a Christian who wants to love both.

Lie 1: ‘The Shack is a fantastical fiction tale.’ But it isn’t truly a novel.

I opened The Shack expecting to defend it a little. After all, many Christians don’t get fiction.

They don’t know what it’s for (a way creative humans reflect God’s creativity).

They have bad reasons to justify it (for “spiritual” means, moral instruction, or evangelism).

Then when popular fiction comes along, they react with fear or loathing, as in the case with the Harry Potter novels (which are great fantasy) or The Da Vinci Code (a comical “thriller”).

When The Shack released in 2007 and hit the New York Times bestseller list, Bible teachers piled onto this little book. At back of their criticism, they seemed to believe Christians really ought not be reading novels anyway. Many of the critics were preacher types. So didn’t they already believe sermons beat any novels any day? How then did they have any credibility?

But I was wrong. It turns out the preacher types, annoying as they can be, were right. They recognized The Shack is not a true novel. Instead, it’s a sermon dressed as fiction.

The Shack is like Courageous, right down to the cute little girl who dies. But even Courageous had more plot and character development.

Novels surely have religious views explored by human characters. But The Shack is more like other morality-driven evangelical stories (e.g. Fireproof or Courageous). Its characters exist solely to explore a religion. As fantasy novelist Kat Heckenbach explains:

What frustrates me more about The Shack than anything is that it is presented as a novel and it’s really not. It’s a book-length conversation. It is the trinity in human form having a Q&A session with a man who is struggling, but it is not a novel.

I feel this is an important distinction. It’s not a story into which an author has interjected a world view. It’s not faulty theology as part of a piece of fiction. The sole purpose of The Shack is to present the author’s theological opinions. It’s an essay written in a story-like style. That makes it subject to theological dissection. An actual novel has the purpose of telling a story, and while we can to an extent dissect the author’s message, we have to keep in mind that that message is only one facet. In The Shack, the message IS the entire purpose. I don’t think we can just go, “Oh, it’s only fiction, so no biggie what the author actually believes.”2

Therefore when we talk about The Shack, we are talking about a trinity of authors (William Paul Young, with front-cover uncredited Wayne Jacobsen and Brad Cummings) who are trying to teach us a lesson. This genre is more like an extended sermon anecdote. So no one can touch the “base” of claiming “it’s only a story” and avoid being tagged with objections to the lesson.3

Lie 2: ‘Only legalists fear The Shack. Christians who like a loving God will like it.’ But graceful Christians also criticize this rather legalistic book.

Some (not all) fans of The Shack take a rather dim view of critics. For example, The Shack coauthor Wayne Jacobsen in this attempted apologetic compares their critics to Pharisees. Among some fair arguments, Jacobsen builds up several straw men. Upshot: if you disagree with this book, then you’re likely a legalistic Christian who doesn’t truly want a loving God.

First, this is manifestly untrue. The Shack criticisms have come from all over Christianity. Jesus-loving civilians, teachers, and authors who have spent their lives opposing legalism and teaching grace have also challenged The Shack.4 To cite just a few examples:

- Our own Rebecca LuElla Miller engaged graciously with The Shack, starting here.

- Author and former pastor Tim Keller gently critiqued the story.

- David Mathis, editor at the grace-based ministry Desiring God, engaged the story on its own terms, especially the themes of pain and suffering.

- Author Randy Alcorn has challenged the book’s theology, such as here and here.

Perhaps criticisms from angry, fearful, legalistic Christians are easier to hear in a crowd. But if Jacobsen is aware of these gracious criticisms, then it is Jacobsen, not the critics, who resists having his mind expanded by complex, spiritual-paradigm-challenging realities.

Second, this slander of The Shack critics is uncharitable. Just because a person looks like a sinful legalist to you, doesn’t make that person a sinful legalist. In fact, that very way of judging—by appearance, based on your own personal stigmas—is itself graceless legalism.

Third: alas, The Shack reflects the authors’ own binary “rules”-based faith. In the world of The Shack, you either accept their best way of seeing God, or you are a type of Christian who favors “religious machinery [that] can chew up people” or “politics and economics” that distract from man’s chief end, relationship rightly defined.5

Old religious fundamentalists feared movie theaters or pubs. The Shack fears institutions, churches with programs, or any hint of political influence. So if some critics are legalistic, they are in great company: The Shack itself offers a form of absolute, unyielding legalism.

Lie 3: ‘Everything in The Shack is a heretical lie.’ It teaches some truths.

More positively, any critic who implies or states that The Shack is only full of heresy should check himself. Do not so slander this book. Like many poor evangelical sermons, and even most secular stories, The Shack can reflect biblical truths and can be commended, such as:

The Shack insists God the Father isn’t white with a beard, like Gandalf. True. But loses geek points for using Gandalf as a negative comparison.

- Jesus “chose to die” and “saved us from our sickness.”6

- God isn’t a white man.7 (The “God the Father as a great white man” image is a stigma that apparently many readers share, though it has never plagued me.)

- “The truth shall set you free and the truth has a name; he’s over in the woodshop right now covered in sawdust.”8 (Bravo, The Shack. Many people misquote John 8:32 and the authors rightfully understand this is a reference to Jesus, not knowledge.)

- God isn’t like us, and is not simply “the best version” of man.9

- God is a trinity and exists as love because His Persons are in relationship.10

- God is not evil, and has good reasons to allow evil and suffering.11

- Jesus promises to cleanse the universe; Heaven will come to New Earth.12

- Our desire for independence from God is the root of all evil.13 But we really have no absolute “rights,” not even to speak uninterrupted by God!14

It wouldn’t even make sense to claim The Shack has only lies or heresy. Wise Christians who believe in biblical truth have always also believed the most effective and believable lies are those mixed with truth. That’s why the apostles teach us to practice discernment. This means sorting truth from error, because the two are often mixed up in complex ways.

It wouldn’t even make sense to claim The Shack has only lies or heresy. Wise Christians who believe in biblical truth have always also believed the most effective and believable lies are those mixed with truth. That’s why the apostles teach us to practice discernment. This means sorting truth from error, because the two are often mixed up in complex ways.

Lie 4: ‘In The Shack, God won’t violate free will.’ Not if you look closer.

That last truthful part, when “Sarayu” (a fictional representation of the Holy Spirit) gently re-interrupts Mack, is one moment where I felt The Shack really shone. I laughed aloud and wished the book were as good as this very counterintuitive, yet very biblical moment.

He can walk through walls. But He would never, ever break down a door. Not even to save you. #MuhFreeWill

And yet the story also insists on upholding, as a highest value, man’s free will.15 Supposedly, God cannot/will not violate man’s will, because “to force my will on you … is exactly what love does not do.”16 But The Shack’s own earlier claim about man’s “independence” streak better evokes the truth of Scripture itself: man is born “dead.” We are enslaved to our craving for independence from God.17

And in fact, even The Shack’s God “violates” Mack’s will several times. (S)he stands by while Mack suffers, despite having advance knowledge of events. (S)he will not share her reasons with Mack—itself an act of power, keeping information from another person. (S)he only offers pat answers that only impress some evangelicals.18

Or consider this imagination exercise:

- Who has a greater amount of freedom in their respective universes: God (as the authors portray him) within reality, or the authors themselves within their story-world?

- Can The Shack’s authors have good reason for “controlling” Mack, as a character, and arranging all events in his world for their good purpose in teaching spiritual lessons?

- Does Mack have absolute “freedom” to choose? Do the authors violate his “free will”?

- Did Mack have free will not to accept the will of “God” and release his “Great Sadness”?

Lie 5: ‘In The Shack, God values love over power.’ Not if you look closer.

Much gilt. Very edges. So Bible.

Furthermore, The Shack claims to oppose all manifestations of human power. “Hierarchy” is contrasted with relationships and only “imposes laws and rules.”19 Jesus hates the idea of institutions.20 As for Christians who think Bible study and scholarship are beneficial to the Kingdom, they get a snarky little paragraph early on:

In seminary [Mack] had been taught that God had completely stopped any overt communication with moderns, preferring to have them only listen to and follow sacred Scripture, properly interpreted, of course. God’s voice had been reduced to paper, and even that paper had to be moderated and deciphered by the proper authorities and intellects. … Nobody wanted God in a box, just in a book. Especially an expensive one bound in leather with gilt edges, or was that guilt edges?21

The Shack’s rhetoric offers a great promise: “We’re going to oppose The Powerful, really stick it to the evangelical Man, because God isn’t restricted by all our authorities and intellectuals!” But it can’t fulfill its own promise due to self-contradictory portrayals of power and institutions. This story ignores its own positive portrayals of power: God as a good judge, God as the only One with answers while Mack questions and complains, Mack and other humans as power-gifted stewards over creation’s gardens and wonders, and even human police officers as agents of earthly justice. The story shows that God and man can exercise power redemptively. Power is not evil. It was originally good, yet can be corrupted.

The Shack does not recognize this fact, perhaps due to its eagerness to reject bad sorts of Christians (whom we do not meet and who are not allowed to speak for themselves). It also fails to consider that if we oppose “power” as intrinsically evil, we will only redirect power to a new ruling party—the new elite who wish to persuade us “they’re not even interested in power.” This is self-evidently absurd, and even dangerous if applied in real-world cultures and relationships. Often it is not truly humble people, but power-craving narcissists, who loudly insist they are not interested in power but only Seek to Do What’s Right.

Anyway, if such new-kind-of-Christians truly don’t care about power, why did the authors join in court battles over book royalties?22 In fact, without rightful power, we could not get books like The Shack. Authors must have power to write a story. Editors, agents, and publishers have power to get it published. Governments have power to enforce contracts and copyrights.

Lie 6: ‘You can’t criticize The Shack because it helps people.’ False.

#AlternativeJesus (Galatians 1:8).

Let us say I grew up in an abusive, amoral, atheistic family, and was confronted by Mormon missionaries. They challenge me to read The Book of Mormon by Joseph Smith, et. al. They suggest if I do, I will feel a “burning in the bosom” that helps confirm God is real.

Let us say I did this, felt the burning, found healing from my unbelief, and converted to Mormonism. Then later I found this book really was bad fanfiction about a false god. Instead, I convert to Jesus Christ the only and forever God-Man Who has spent the last 2,000 years redeeming saints for His Kingdom (e.g., He didn’t go on hiatus until Smith).

Would I thank God I read the Book of Mormon for at least getting me started? Maybe.

Would I despise nice Mormon people for wanting to help me meet “God”? Surely not.

But would I praise the false Book of Mormon because God used it to draw me? Not at all.

It’s complicated. So it is with The Shack. Maybe the Lord has used this book to draw you away from some false teaching and toward Himself. In that case, this is wonderful. We will not discount this, or reject your praise for His grace. And thus critics of The Shack should be more careful about judging the motives of its fans. But let us praise the Giver, not the gift (which may be greatly flawed otherwise). And keep moving toward the Source of all truth.

Continue reading at Six More Lies Christians Believe About ‘The Shack’ (coming Thursday, March 16).

- The distinction matters. A person who believes false teaching, especially through ignorance or accident, could still love Jesus and be redeemed. A person who accidentally falls into a heretical teaching, such as the “prosperity gospel,” may still love Jesus. But a person who willfully rejects biblical teaching and worships another Jesus is a heretic. ↩

- From a social-network conversation. Reprinted with permission. ↩

- Also, Christians should be the first people to avoid dismissively saying “it’s only a story” in response to someone challenging a story (or the value of stories at all). How would you feel if you praised the story and someone dismissed it with “it’s just a story,” e.g. “settle down and stop being weird”? Story-making is part of God-given humanity. Stories are powerful. And in an evil age, we can use such powerful gifts both for great good and for great evil. Even The Shack’s version of Jesus shares this view of imagination’s equal power and dangers: “Such a powerful ability, the imagination! That power alone makes you so like us. But without wisdom, imagination is a cruel taskmaster.” (The Shack, 143). ↩

- However, these teachers and ministries do oppose legalism not merely because “it hurts people.” After all, people can claim to be “hurt” by truth. They oppose legalism because it is contrary to the Gospel that Jesus brings us as revealed in the written word of God. ↩

- The Shack, 183. ↩

- Ibid, 33. ↩

- Ibid, 33. ↩

- Ibid, 97. ↩

- Ibid, 99-100. ↩

- Ibid, 103. ↩

- Ibid, 127-128. ↩

- Ibid, 179. ↩

- Ibid, 134. ↩

- Ibid, 139. ↩

- Ibid, 127, 147. ↩

- Ibid, 147. ↩

- Ephesians 2:1-10. ↩

- This leaves secular reviewers, like Peter Sobczynski, less impressed: “As near as I can figure from the somewhat murky thinking on display, God is responsible for all the things that are good, pure and beautiful in the world but always seems to have an excuse when it comes to the uglier aspects of life. If one has the temerity to press this particular issue, as Mack understandably does, all he gets in return is a bunch of straw man arguments that pretend to answer his questions without actually doing so.” The Shack, Peter Sobczynski, review at RogerEbert.com, March 3, 2017. ↩

- The Shack, 125. ↩

- Ibid, 181. ↩

- Ibid, 67-68. ↩

- The flak over ‘The Shack,’ Sarah Weinman, Los Angeles Times, July 13, 2010. See also The Shack Gets Sued, Steve Laube, July 14, 2010. It seems the end of this suit allowed The Shack to be made as a motion picture, which is why it’s so late arriving. ↩

Very well thought out and an honest review. As a broadcasting professional I know the power of media first hand so my desire is that this movie tanks and tanks badly. It’s much easier to make people believe a lie using a film then it is a book because of the nature of the media. Music, editing, camera angles and acting, if well done, can convince those with little discernment of just about anything. I didn’t read the book, I studied it, not for myself but to write a paper on its bad doctrine so I could help others to see The Shack at face value. Let’s keep up the good fight. Thanks

Steve, do you think it’s because of our society’s preference for movies and TV to books that we are so easily deceived?

A excellent, gentle critique of the film/book.

I guess I’d say that I somewhat disagree with the “not a novel” view. Don’t get me wrong, I totally see where you are coming from, but I don’t want to over-burden the authors with needing to dot every literary “i” and cross every genre “t”.

I will agree that it isn’t just a novel. No matter the authors’ intent, I do think that it brings up some good mental exercises for the reader.

eg: God isn’t Gandolf.

My question: who truly grew up thinking of God more like an old white-bearded man rather than the Person of Jesus? I was exposed to the white-beard image, but didn’t struggle with it. For the saints, God looks like Jesus, Who is His exact image.

1) But Jesus appears as a white man in most visual representations so there’s that.

2) Most any visual art example of God the Father that I can think of is an old white man like Michelangelo’s Creation art in the Sistine Chapel – just Google image search “God”

If you grow up in a family where God is more than just an abstract religious concept then I think the struggle is lessened because the old white man imagery isn’t the primary way you experience Him. But if God is mostly just your cultural background then I think the old white man thing does get rooted in more.

The link just before the footnotes doesn’t work.

Thanks for this post!

The link jumps the gun. 🙂 Part 2 will be available next week.

Good article, Stephen. Thanks for linking to the first post in my series. I like the fact that you called The Shack out for not being a novel. It isn’t and the whole “it’s fiction” thing, allowed lots of people to accept it without thinking about it deeply. That’s a frustration to me in and of itself, because I think we should think about the fiction we read, not just go with how we felt about it.

Becky

We need more patience and kindness with one another in discussing this book. Good feelings do not equal sound doctrines. But there are bits of truth throughout the work. And yelling at others–uncharitably–for their lack of discernment is itself a form of blasphemy.

I have problems with “sweet Christian romance” novels for a couple reasons. I quit reading them in my early twenties. But I refrain from discussing these problems with women who can occasionally indulge in these cloying sweets without growing sick.