Speculating About The Known

Last Friday, on my own blog I discussed truth in fiction. In part I looked at an article by Travis Prinzi at the Rabbit Room (where Andrew Peterson, Pete Peterson, Jonathan Rogers, and others interested in speculative fiction also hang out) which explored the Christian fantasy tradition established by the authors many think of as the founders of the genre.

Last Friday, on my own blog I discussed truth in fiction. In part I looked at an article by Travis Prinzi at the Rabbit Room (where Andrew Peterson, Pete Peterson, Jonathan Rogers, and others interested in speculative fiction also hang out) which explored the Christian fantasy tradition established by the authors many think of as the founders of the genre.

What struck me forcibly was that Tolkien, Lewis, MacDonald, Chesterton, and L’Engel all seemed to consider their speculative writing to be a means of revealing truth. In contrast many speculative writers today, including some Christians, look at their fiction as a means of discovering what they believe to be true.

Most notably, perhaps, as I’ve mentioned before, Anne Rice stated that her vampire novels served to help her work her way to faith:

But though they didn’t include Jesus, the writer … says her previous books have always pursued questions of morality. From the vampire Lestat to the devil Memnoch, all her heroes are immortal outsiders who have supernatural powers and who live in worlds where right and wrong matter deeply. If the Russian novelist Dostoevsky had his Grand Inquisitor interrogate Christ in “The Brothers Karamazov,” Rice conducted her own theological investigation in “Memnoch the Devil.”

“The books in a way are like stations on a journey,” Rice said. “They reflect different points on a lifelong quest.” (“Anne Rice: ‘Stations On A Journey’ ” by Marcia Z. Nelson at beliefnet)

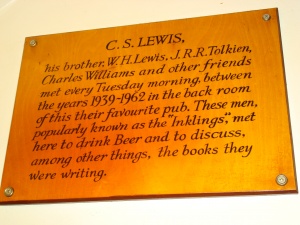

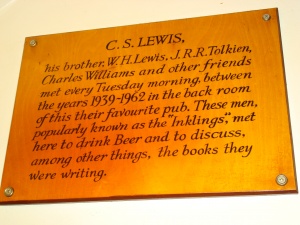

C. S. Lewis’s “supposal” and J. R. R. Tolkien’s subcreation stand in stark contrast to this discovery quest method of writing.

Lewis clearly started with the known — God — then speculated to what truth would look like in the imagined world of his creation.

I did not say to myself ‘Let us represent Jesus as He really is in our world by a Lion in Narnia’: I said ‘Let us suppose that there were a land like Narnia and that the Son of God, as He became a Man in our world, became a Lion there, and then imagine what would have happened.’ If you think about it, you will see that it is quite a different thing. (Walter Hooper, Literary Criticism, 426, as quoted by Joe Rigney in “Narnia Helps Us Live Better Here” at desiringGod)

He elaborated further:

If Aslan represented the immaterial Deity in the same way in which Giant Despair [a character in The Pilgrim’s Progress] represents despair, he would be an allegorical figure. In reality however he is an invention giving an imaginary answer to the question, ‘What might Christ become like, if there really were a world like Narnia and He chose to be incarnate and die and rise again in that world as He actually has done in ours?’ This is not allegory at all.

(from a letter to a Mrs. Hook in December 1958, quoted in Wikipedia)

Nowhere is there a suggestion that Lewis was unclear about God’s nature or plan or purpose or manner of relating with His creation. In fact the opposite is true. Because Lewis knew these things about God, he could speculate what God might look like and how He might act if the world were one Lewis imagined.

As I look at our western world today and consider the prevailing postmodern and humanistic beliefs, I conclude that many writers, including Christians who claim to believe the Bible, have abandoned known truth for a type of agnosticism.

In a recent discussion (the other half of what prompted my Friday post) at Christian supernatural suspense author Mike Duran’s site, a number of commenters took this “unknowable” approach to explain why Christian writers couldn’t be held to a high standard for showing God realistically in fiction.

At one point, the idea surfaced that we shouldn’t base our theology on our fiction. True, I think, but perhaps writers should base our fiction on theology.

The idea also came out in the comments at my site that such an approach might make it hard to write good stories:

Depicting God in fiction, as I see it, requires a specificity that can actually stilt our storytelling.

While I don’t believe this is so in fantasy, I don’t know if that’s true about stories set in this world. However, good stories, by the definition of “good,” seem to me to require truth. Art has long been understood as the marriage of beauty and truth. How can a story be better if it is fuzzy about Truth? And why would anyone want to write such a story? That would be like saying it’s critical to care for the body of a car while neglecting the maintenance of the engine.

I can’t help but wonder . . . perhaps no new C. S. Lewis has surfaced in the past fifty years for the very reason that so few writers are starting with the known and speculating from there.

Excellent point–you can discover things while wandering through the wilderness, but it means so much more when you have a guide.

Galadriel, what a great image. Thanks for that.

Becky

Great post, Rebecca.

I just returned from a meeting with some fellow apologists and we talked about this very issue. They were absolutely fascinated that I was an author and an apologist. I had to remind them that one of our heroes in apologetics, C. S. Lewis, was a very successful fantasy author. You should have seen the lights come on!

What followed during our seminar was a course of storytelling. Our facilitator had us acting out stories as illustrations for our presentations on apologetics. I found it interesting that he believed in today’s culture, we have to reach the heart with emotion before we can engage the brain with the academic truths of apologetics. Sounds like writing a story! With my background as an author and dramatist, I had a blast. I even commented that I believed we had to combine apologetics, or seeking truth, with art to impact our culture. Why? Because in our postmodern world it seems we are writing from the position of “Can we know truth?” when in fact it should be the other way: “Truth can be known.”

Thanks for a great post and I’m looking forward to more comments!

I don’t like “The Shack” for this reason – the writer portrays God in a manner that is inconsistent with the truth of God’s Word. Because the Lord has revealed the beauty of His character to me, I feel compelled to write. I can’t imagine being inspired by anything less.

We really need to keep in mind that our country is in a state of RAPID spiritual decline. We desperately need revival. My prayer is that the Lord will bless our efforts to reach our culture for His glory.

Sarah, I wrote a ten part review of The Shack. The book received so much positive response, but I thought readers needed to look deeper.

That’s the thing about stories. They can move us — touch our hearts, make us feel deeply. But sometimes that feeling will be supplanted quickly by the next Thing, be it funny or sad or exciting.

What I want to do is touch readers and make them think. The stories that change me stay with me, make me cogitate and eventually re-read them.

I’ll tip my (virtual) hat to The Shack for getting people to talk about some faith issues. Sadly, Mr. Young introduced a lot of Rob-Bell-ish false teaching. But that’s why we need to read with discernment and write our own truthful stories about God.

Becky

I think The Shack is a good example of how not to write fiction. Most of the time, I just write and let the story go where it may wander. I do try to make sure that my writing honors God to the best of my ability; that being said, I don’t have a doctorate in theology or a degree in higher education. I do read–alot–and I love Jesus and hope that Jesus reaches those out there through my fantasy fiction.

Heheheh. I don’t think a degree in theology is required, Nikole. 😀

I do think, however, we can know God and write from more than “my experience of Him” as some might think. There are objective truths about God (besides that He loves us) that can form the basis of our stories if we choose to do the work.

In that vein, I guess it’s hard for me, an outliner, to envision how a seat-of-the-pants writer would go about doing this. From the outside looking in, it would seem to me that a writer could end up writing the same story over and over if left to write whatever comes out. To be honest, I’ve seen a bit of that in my own short story writing.

Anyway, thanks for joining in the discussion.

Becky

Bruce, thanks for your comment. What a great experience — conferencing with a group of apologists and doing so in a way that utilizes story.

Without a doubt, our culture values story, but I think we have to be careful not to get caught up in the “entertainment is king” mentality. We are borderline hedonistic here in the US.

Christians, I believe, should want to do more in our stories. Writing, as I say from time to time, is a form of communication above all else, so we really need to have something to communicate.

We can be like little kids who scribble off a crayon picture and carry it to Mom as a “special present,” which we all know isn’t ever going to win any art show. Or we can be purposeful and study and dig deep and ponder and pray and consider the needs or our neighbors and work and write and rewrite and revise and edit and rewrite and pray and rewrite … In other words, showing God in fiction, and doing it well as Lewis did, is serious work.

A good many others have likened Christian writers to the two men charged with the main artistic work of the tabernacle. I think it’s a good comparison. God has skilled us and we are to work at our craft. What we produce is to be beautiful and it is to have a function — perhaps for worship, like theirs.

Becky

You’re absolutely right! Writing something about God and not really saying anything of substance is tantamount to clanging cymbals and sounding brass. Your references to The Shack remind me of this tactic. It was a very moving and symbolically sound bit of prose, but the theology was all whacked out and frankly, wrong. What I loved about my recent seminar was that our instructor never wanted us to change the substance of our presentations. He wanted to preserve and advance Truth. The Truth had to remain. What he wanted us to do was to somehow convey that Truth in a winsome and attractive way that would catch people’s attention, engage their emotions and their minds and perhaps change their lives forever.

I have to continually remind myself this is my job as a Christian author. There are many times I want to wander off course and chase metaphorical rabbits because the story demands it. However, if that path leads away from Truth and into the realm of Lie, I have to correct it. We can always stay true to the Story if we remember where we write from and that is from our theistic worldview. As authors, it is our worldview that frames the story just as every piece of fiction or non-fiction conveys the author’s worldview whether the author intends it or not. I agree with you. We must always keep God’s truth at the core of our stories. Why else would we write?

I love the fact that one of the most timeless and lasting methods Jesus used to teach was through storytelling. He gave us the perfect format for those of us who “can’t not write” to use our God given talent (or, curse, whichever way you look at it) to advance the Kingdom. We are shapers of story and tellers of Truth and we must always remember our responsibility. Thanks again for a great post that has given me a lot of encouragement and a lot to think about.

Becky, I wholeheartedly agree, and I’m glad you’re addressing this aspect of the writing craft here and over at your blog. The stories told in Scripture reflect truths about God and the workings of his kingdom, and we should seek to follow in those footsteps.

Madeline L’Engle has an excellent quote on this topic:

I would add that we further the coming of the kingdom by depicting God’s character and nature accurately in our writings. Of course, we will make mistakes sometimes, but it’s worth investing the time and energy into this area of our craft, because it matters more than we know.

Thanks for the encouragement, Sarah.

I agree. And I think that’s part of our mandate as believers. It makes sense for writers to write what we know and believe. It also makes sense for us to do it well. I don’t want to lose sight of the “beauty” side of art either.

Becky

Becky, your column would have been encouraging and “inspiring” in all the right ways on any day, yet yesterday your gentle yet steadfast commitment to truth, along with your commitment to solid storytelling and craft-honing, was even more encouraging to me.

Your simple division of the two different methods — fiction as exploration to find truth, or fiction as exploration of existing truth — will henceforth be part of my personal rhetoric.

I think we all know of many books we’ve read that seem to lack the oomph of The Chronicles of Narnia. And I don’t think it was because C.S. Lewis was a once-in-a-millennium genius, or because readers were more open to fantasy then (not true; he and the other Patron Saint, Tolkien, made them open), or because postmodernism hadn’t occurred and made us all crave relativistic or dystopian stuff (not true; see Lewis’s own The Abolition of Man for proof then, and the modern popularity of there-is-truth-based stories for proof now!). The question then becomes: why the shift anyway?

Again we find that the problem runs deeper than simple shifts in fiction preferences. As much as I’d like to pick on favorite targets — Prairie Romance or Simple-Minded Readers and/or Christian Publishers, etc. — they’re the fruit, not the root.

The problem is that more Christians have adopted postmodernism, or emotionalism, as a substitute for loving the God Who reveals Himself.

We saw that again yesterday, I contend, when a few well-meaning commentators took issue with the idea that God’s personal “leading” of His people in modern times (if He does this, which I believe He may) is equivalent to His Word, or fills in the gaps that the insufficient Word simply leaves out and which we supposedly need filled.

It’s a fascinating discussion, which may not be over, and I believe that we see not only examples of agnosticism when it comes to revealed truth, but Gnosticism. “God’s Word about Himself is not enough for me. I need to seek a Secret Knowledge in addition to, or even over and above, what’s written in the Bible, a custom revelation for me.”

But often in response to claims that God is loving enough to tell us some about Who He is and what He’s done, come rebuttals such as “You can’t pin God down on a card” or “You can’t dissect God like a frog.” These are overcorrections, and silly ones besides.

Rather, Christians who love the God of the Bible are simply saying, “We’ve missed the fact that God is loving enough to reveal Himself enough to be known by His people so we can find our joy in Him alone! Moreover, those who claim only ‘God is a mystery,’ as if overanalyzing Him is a person’s only potential problem or issue worth fighting, will lead us right back into the same legalism and feelings-worship that slander God’s Name, set back His Gospel and His Kingdom, and hurt and spiritually abuse people.”

Fiction isn’t distinct from this reminder. It fits neatly within that renewed Gospel call. After all, Christ Himself did not tell parables simply as means to Social Action, or as encouragements to listen to our feelings to discern His will, but to back up His intense nonfiction teaching: the Kingdom isn’t just coming, it’s Here; repent!; Who do you say I am?; This is what God is like; and This is what Kingdom behavior looks like.

I’m not yet convinced, either, that a Christian novelist who begins with even the very un-Lewis-like thought of I want to write a story to say something about Christianity will necessarily write a bad story. It may be that basing a story on Truth will naturally make the story better than one based on mere “exploration.” One thought to explore …

Finally, I still wonder whether even the shallow sorts of fiction that seem to be based on “let’s see what God may be like, in this story,” are merely putting on a pretense anyway. That may be based on the Megachurchian, seeker-friendly notion that a Christian should hide who he is and what he’s about until the last possible minute, like a door-to-door salesperson. This is not only un-Biblical but ridiculous: it insults people’s intelligence and assumes they’re weak and will get the vapors if someone, whether civilian or novelist, proclaims up-front and winsomely that he’s a Christian. Of course, some people really do claim to be that weak, but I would suggest they’re faking it too.

“Finally, I still wonder whether even the shallow sorts of fiction that seem to be based on“let’s see what God may be like, in this story,” are merely putting on a pretense anyway. That may be based on the Megachurchian, seeker-friendly notion that a Christian should hide who he is and what he’s about until the last possible minute, like a door-to-door salesperson.”

Well, in some cases that might be true. But for me – and this is the point I hear these folks making – it is not this at all. Rather, it is the fact that this is an objectively Christian world regardless of what people think and regardless of whether anyone ever points that fact out. The truth of the Trinity blazes forth from the very creation, so much so that people have to forcibly repress it (Romans 1). Since this is the case, simply presenting the world just as it is – as a broken, warped, redeemed place of buzzin’, bloomin’ confusion – we are actually presenting Christ, because we are subversively attacking those repressing instincts.

Really, this is the entire point upon which my entire opinion of Christian artistry hinges. We don’t have to choose religious topics, or even include one second of overt Christian theology in our work – if we are presenting the truth about the world. Like the Dutch painters who began to simply paint ordinary houses and people, rather than saints with halos, they could also present truth, even True Truth, without a single word of religiosity. Don’t have to, but we’re certainly not forbidden to do so either.

Adam, this is a well-articulated point. I just had a discussion last night with a friend about this very subject.

I completely agree that we don’t have to choose religious topics. Lewis didn’t. He chose a make-believe world and a lion who ruled it. His theology was not overt, though our familiarity with some of the great lines containing theology may make it seem so.

I’m seeing something between ordinary houses and saints with halos, however. I don’t believe ordinary houses proclaim Christ. The point of Romans 1 is that God is seen in what He made. But why did Christ have to come, if that revelation was enough? Why was the Bible given us if all we needed was nature?

I don’t think it’s wrong to write stories that reveal the world in its fallen state. Men need to know our condition apart from Christ. Men need to realize they are denying their maker. Hence, Rom. 1 stories, if you will, have an important place and purpose. Not all stories have to be about the act and fact of redemption. People who don’t know they’re lost aren’t looking for a Savior.

But isn’t that still starting with known truth — Man is sinful, so I’ll paint that truth, as opposed to, I’ll write to discover Man’s nature?

Thanks for taking part in this interesting discussion.

Becky

Rebecca,

I think there are several problems with your argument. The most prominent problem is that while Lewis and Tolkien did both search for God, neither of them agreed on who God was. The Catholic and Protestant conceptions of God are very different and many born-again Christians would still argue that they do not agree with the Catholic elements of Tolkien’s Christology (particularly his invoking of Marian overtones through Galadriel, who seems superior to at least one of the Christ figures in the novel, Frodo. Though Tolkien did warn about reading too much into those Marian overtones).

Also, there is nothing wrong with exploring theological hypotheticals. For instance, I could imagine a novel that posits a godless universe as being deeply Christian, especially if it points out why the Christian author would find that a sad or depraved universe. In fact, Dostoyevsky’s The Demons (also known as The Possessed) engages in this kind of speculation very successfully, devastatingly critiquing modernity and postmodernity (“Without God, everything is permissible” Dostoyevsky quips).

I’m sorry, but coming from a more liberal Protestant background (though with evangelical roots), I feel that all this talk of “dirty fiction” and “swear words” and “realism” shows just how absolutely primitive evangelical, born-again fiction is. Catholic writers don’t have these problems – read Graham Greene or Walker Percy, if you don’t believe me. You need to be focusing on evangelical writers’ still pitiful command of style and aesthetics, before moving on to consider your works theological ramifications. No one’s going to respect you if you can’t write, and they won’t respect your theology if it isn’t well thought out . . . which frankly, is a problem of much evangelical fiction that I’ve read. I really advise any evangelical authors here to check out Leif Enger or Charles Colson’s Gideon’s Torch. These are the only two quality evangelical texts I know written by evangelicals, and I’ve read hundreds. Stephen Lawhead’s books can give good tips on writing as well. But this debate isn’t even on the right issues right now.

John, thank you for mentioning Walker Percy and Graham Greene! We do really need to pay much more attention to their likes to begin making a solid impact. While I don’t share your liberal protestant views, as a robust evangelical I can attest to the problem you bring up. We need to do a better job studying Flannery O’Connor, G. K. Chesterton, even the greats of classical and medieval lit, like Chaucer and Shakespeare – both Christians, and both telling profound truths about the world in all its glory and depravity.

I have found Hans Rookmaaker’s book The Creative Gift a profound evangelical meditation on just this very thing. And has anyone here read anything by Leland Rykan? The Christian Imagination is a wonderful symposium on the subject, as is his The Liberated Imagination. Jeremy Begbie has some spectacular work on the subject, such as his magisterial Voicing Creation’s Praise.

Rather than resisting your comment, I at least want to own and admit it: “You need to be focusing on evangelical writers’ still pitiful command of style and aesthetics.” We need to study these authors and pay attention to not only how they write, but how they integrate their worldview into their stories. We need to ask how novels like The Pillars of the Earth, Ian McEwan’s Atonement, Cormack McCarthy’s The Road and Peace Like a River utilize all the elements of their craft. But not only them. How does Babylon 5 capture serial storytelling? How did narrative drive make the Potter books so good? Moreover, how do non-Christians build their own viewpoints into their works, and how can we imitate them with subversive power?

Hi, John, thanks for adding your thoughts to the discussion.

I’m going to disagree with a couple points you made. Let me start with the most obvious. Though Lewis and Tolkien were not like-minded in their religious expression, and did differ on things like belief about Mary and the sacraments, it is a stretch to say they disagreed about God. I’d also say, they weren’t “searching for God,” since from their own writings it’s clear they believed they had met Him and knew Him. The both believed Him to be the Creator, the All, the giver of life and the redeemer of it. They believed Him to be good and powerful and sovereign.

The second point has to do with this statement:

I guess this isn’t so much a disagreement as it is a question — what in the things I said led you to believe I was talking about “dirty fiction” (?) or “swear words”? Realism, I’ve discussed in depth as that which should above all be real about God. So I am certainly not standing against realism, just the application of that word to refer to only that which has to do with mankind.

Here’s the final point of disagreement:

I am not suggesting that we should pay less attention to beauty, John, but more attention to Truth. Christians have been told ad nauseam that fiction shouldn’t be “preachy,” and hence themes have been scrubbed from our stories. Instead we now have “faith elements,” some little tip-off that a character is a Christian, such as a quick “God help” in the midst of a great crisis or a “somebody must be watching over me” line. These are banal at best and anti-Christian at worse.

Too many stories, then, end up being shallow — and shallow stories don’t demand great art. Revision ends up having little to do with creating a more artistic story and more to do with checking to see if the hero has the same eye color at the end of the book as he did at the beginning.

If we start with Truthful stories about God as much as about Man, we have a reason to craft them in a way that is fitting to such universal and lasting themes.

In a recent post on my personal site, I explained it this way:

I guess, in the end, I’m saying we need both Beauty and Truth — and in the latter we must not neglect the Greatest Truth.

Becky

I really like John’s comment here and agree with much of it. Becky, I think you may be creating a false dichotomy between these two methods of storytelling. Anne Rice is liberal and postmodern, so naturally I would expect her storytelling to bear that out. However, that is not an indictment of the “discovery method,” as you call it, as much as Rice’s conclusions that religious truth is relative.

I’d suggest the “discovery method” is not necessarily tethered to a postmodern worldview, for two reasons: (1) We see through a mirror dimly, so even the most enlightened of believers IS still discovering the depth of the “love that surpasses knowledge” (Eph. 3:19). And as John points out, even the greatest religious thinkers arrive at some different conclusions about the Truth. (2) Discovery is a necessary as a fictional process. Even if the writer knows where she’s going (i.e., has a handle on the Truth), the reader may not. And may not want to. As such, “babes require milk” not meat. Which is why it is near impossible to extrapolate hard theology from the LotR and The Chronicles of Narnia.

Hi, Mike, I appreciate you stopping by and adding your thoughtful comments.

I won’t rehash what I just wrote to John, but let me address the last part of your remarks — your response to my delineation between a writer discovering truth and revealing truth in his stories.

What I find interesting is that we have a lot of agreement that we shouldn’t base our theology on our fiction. What then, I wonder, is a writer to base his theology on? The “discovery method” would seem to suggest he bases it on the things he contemplates as he creates his story. This, if fact, seems to be nothing more than arriving at an understanding of truth through fiction.

I don’t mean to suggest that all of us aren’t growing in our understanding of God. Paul, in fact, told the believers in Colassae,

Peter also saw the need for believers to “grow in grace and the knowledge of God” (2 Peter 3:18).

So I’m not suggesting that we’ve arrived. I do think, however, Scripture is the place for us to go to learn and grow, and prayer is a means by which it can be accomplished.

Can God teach us more as we write? I have to believe He can. I just question whether that’s the best strategy for writing a meaningful story.

Lastly, I’m not sure what you mean by “hard theology.” I know it’s possible to extrapolate from Narnia a number of truths about God, not the least of which is His willingness to sacrifice Himself for a sinner. Then there is His work as Creator, His sovereign nature, and a handful of other truths that don’t take much digging to uncover. Lewis’s other fiction has a good deal more to say about God and His relationship with man.

In addition, I’ve read a number of articles about Tolkien, including several that discussed his ideas about good and evil as depicted in his fiction. He also believed in God as the only one who could create ex nihilo. His whole world and the concept of subcreation seems to point to the truth about man made in God’s image. I suppose someone could argue that we only learn of this from Tolkien’s essay and letters, not from his fiction. Perhaps. But I think the point is, Tolkien held those beliefs and wrote from those firmly held positions — he didn’t discover God to be creator in the process of writing.

Becky

Rebecca, thanks for your insightful questions. They really are important to think about, and I would never say I’ve got the answers worked out! This really is the nub:

“I’m seeing something between ordinary houses and saints with halos, however. I don’t believe ordinary houses proclaim Christ. The point of Romans 1 is that God is seen in what He made. But why did Christ have to come, if that revelation was enough? Why was the Bible given us if all we needed was nature?”

Well, Christ came to take away sin and bring in the Kingdom, not to strictly give us kn0wledge. We need more than nature, of course. No one is denying that. My point was simply that Christians can relish and depict the world as it is without the agenda of making Biblical truth obvious because the world as it is happens to be a Christian world. We can present truth, even the Truth itself, simply by reveling in this world.

I have a tremendous problem with the idea that an ordinary house does not proclaim Christ. It is true that Romans 1 teaches God is known through what He has made – and this includes His Trinitarian being (Rom. 1:20). Unbelievers repress this. Yet the rocks and trees all proclaim “God made me! I love God! God is Three in One!” Jesus Himself even said that if there was not a single person left to proclaim God, the very rocks would begin to cry out. Even if we lived in a world where no one was a Christian, it would not change the fact that God made it and everybody knows it. It would not change the fact that the world is suffused at every moment with Trinitarian grace. That ordinary house is a Trinitarian house, regardless of what anybody thinks about it. Every molecule in that house is screaming at every second that God made it, and actively upholds it at every moment.

The implication (at least, the one that I hear!) is that if the house itself cannot proclaim Christ just by being, then the Christian cannot present that house as it is and it be a Christian painting of a Christian house. This then also implies that one must tack onto reality some sort of super-nature in order to make the house able to be presented as Christian like the refried gnosticism of a Thomas Kinkade painting.

Theologian Doug Jones, in his article “Who’s Afraid of Flannery O’Connor?”, says that “In this way, Flannery’s writing again imitates divine love for the ugly and self-righteous. This is the gospel: “While we were yet sinners. . .” On top of this, when you read a group of her stories, a pretty amazing pattern emerges. You soon realize how her visitations of dark grace stand out as huge gifts when compared to actual life. Most people’s actual lives seem to be Flannery characters who never have the privilege of meeting dark grace. Think of the people around you. Think of the secularists. Most go on for decades in their self-deception and selfrighteousness and pettiness until their bitterness just grinds to a close at the end. No revolutions. The majority of people have always seemed to live tedious, small lives. But in Flannery’s world, it’s as if dark grace intrudes regularly. People who would have probably been handed over to let their sin slowly destroy them get this amazing explosion of grace that turns them inside out. Because of this, her stories start to read like gift after gift after gift. You start to long for more dark grace in actual life since it produces such wonderful turns of redemption.”

This is what I mean when I talk about portraying the world for what it is. It’s not that the world is a cold, dark, hard place of fallen corruption and vice. That’s not my story. I’m into grace, and I’m into a world suffused with it from warp to woof. But grace is rarely fun. It’s not prancing unicorns and a happy little elf. Grace is dark. Grace is bloody; it skins your knees and tears you apart inside. But it does this for your betterment. Grace is the cross. This kind of grace doesn’t come down from a supernatural place. it comes from the Spirit working within this world, through this world, and often without us even knowing. Flannery presents grace to her characters – yet rarely if ever does she mention where this grace comes from or who is doing the offering. It happens “in the Name of Jesus,” but she doesn’t blurt it out. Here’s Jones again, in a stellar essay titled “How Not to Watch Films Like a Twelve-Year-Old”:

“Natural revelation reveals Triune style more indirectly. We see a gray mountain or an ocean or the interior of a plant, and they don’t come with labels. They don’t have big banners pasted on them that say “The persons who made this are majestic and surprising.” No. We have to infer that from God’s works of arts. We have to infer divine style via the hints and indirectness of nature. Natural revelation shows us that Triune style overflows, wastes, and loves detail. Some of God’s best handiwork is hidden in ocean depths we’ll never see. God reveals His comic style in walruses and orangutans, his ugly style in hyenas and eels, his elegant style in hawks and horses. “Can you hunt prey for the lion? Or satisfy the appetite of young lions….Who provides food for the raven?” Triune style loves and shouts out to us through all these. “The heavens declare the glory of God, and the firmament shows his handiwork. Day unto day utters speech.” Speech, and yet it doesn’t speak like special revelation. Pines and palms speak without words, without labels. We have to work to understand Triune personality. We have to infer and interpret and conclude. We don’t get a narrator explaining most of God’s revelation. Just hints, and we’re expected to gird up our imaginations.

“But we do know that He is the epitome of interesting personality. In fact, we might define interesting as the Trinity, because reading off Triune life from nature we have to conclude that Father, Son, and Spirit are surprising, unique, tense, paradoxical, unified, different, communal, precise, hilarious, frightening, and “ugly.” And it’s the (somehow) simultaneous combination of all of these that captures Christian divine style. That’s what we look for in ourselves, in others, and in films. That is the image of God in man.”

Great comment, Adam. I’ve been thinking about a few of your points for some time.

To be honest, I don’t know that we seem to be in disagreement over the central issue of my article — that we should be writing from known truth rather than writing to discover truth.

You said;

I certainly agree that Christians don’t have to write with an agenda of making Biblical truth obvious. Perhaps I’ve been unclear. A known truth based on the Bible is that Man is a sinner. I don’t have to announce that in a story or have Christians praying for a sinner or even have that character repent. I can write truthfully about man’s sinful condition by showing a character act from a sinful nature. After all, our condition also fits in with Romans 1 truth.

It’s not up to the writer to make sure readers “get the point.” I’m not saying that the truth of our stories needs to bash people on the head.

I do think, however, coming at a story knowing what I believe to be true will change my writing. It’s not a discovery process. It’s a revealing process.

We still differ on what reveals God, however. I don’t think showing this world necessarily shows God. It can, as I said, show some truth such as man’s sinful state. But as I’ve thought about your assertion that this is a Christian world, I’d say I have to disagree. This world is fallen. The marred image of what was once good is not Christian. Only the redeemed and soon to be glorified world is Christian.

It is because of God’s grace that we can still see His glory in what He made. Christ needed to come, though, because we still would not know God. By the way, Christ did come to give us knowledge, or more accurately, revelation — He showed us the Father and He brought us into His presence.

If we writers settle for painting the world, just painting the world, we will continue writing Rem. 1 stories. Nothing wrong with those. They need to be written. But I think it would be a challenge to write about God revealed through His Son. As I see it, that picture would be more complete. It wouldn’t settle for a grayscale but would stretch to show the picture in living color.

I’d like to see us at least try.

Becky

Good stuff, Rebecca. I suppose it would depend upon what you mean by “revealing” versus “discovering” truth. There is one sense in which I agree, and yet another in which I do not. I agree in the sense that we are revealing our faith and our beliefs.

But I disagree in another way, because the creative process is always one of discovery. Stories emerge from the deepest unconscious part of the mind, and I at least feel as though I discover them rather than create them myself. Similarly, many times I’m not even sure what a story is about until I’m in the process of writing it. I know it was the same for Lewis and Tolkien. So the thematic “message” of the work is found or discovered, not revealed intentionally by the author, at least in the beginning. To come to a story having already “made up my mind” about where the story can and can’t go short-circuits the creative process. Our finite view is so much smaller than God’s; He has taught me many things through the discovery of truth while I write, because I trust that my faith is something that is deeply internalized within me, and so my deepest subconscious will, led by God, draw out truths for me to reveal simply by way of writing the story I need to tell. For me, we can’t know everything, and thus if we shut down the idea of being taught new truths we actually limit our ability to create.

I think you are not seeing other elements in Romans 1. You seem to limit its meaning to nothing but the revelation that we’re sinners. Sure, that’s a big part of it. You won’t get any argument from me that this is a fallen, corrupt world (I’m a calvinist on that point). Yet, theologically speaking, Christians have always insisted that even fallen men still bear the image of God, broken though it might be. This world is, to co-opt a phrase of Flannery O’Connor’s, “Christ-haunted.” Christ, the Eternal Logos, is constantly present in this world, upholding it all at every moment. Just read Colossians. Just because man fell, that doesn’t make this any less God’s world.

To say that only the redeemed bits of the world is Christian is to drive way too close to the edge of the gnosticism pit. A bit too near the “this world is bad, so we must huddle up with the redeemed” for me. It also seems to ignore some of the cosmic implications of Christ’s death and resurrection. Even if we were to grant that the fallen world was not God’s before Christ came, we still have to deal with the Cross. Christ came to take away the sin of the entire world; He was the propitiation of the entire world, not just that of believers (1 John 2:2). This isn’t universalism; people still go to hell. But as a covenant whole, Christ cleansed the entire world. That “redeemed” and “soon to be glorified” part of the world you wrote about is actually the entire creation (Rom. 6). Not all the people in the creation, but the entire creation as a system is progressively restored.

And what I meant by “Christ did not come to give us knowledge,” was that Jesus came to do something, not just talk about it. I was reading “knowledge” as an intellectual exercise, sitting around and chatting about the gospel. Jesus’s primary reason for coming was to do something; He came to die and be raised and cleanse the world and bring in the Kingdom and ascend to the Throne, there to remain until all His enemies are put under His feet.

Hey Adam — you seem to be referring to the Biblical teaching of common grace. I do think a lot of Christians fail to apply that consistently, or of course they overextend and veer into “man is neutral” Pelagianism. But here’s what we have in the site’s belief statement, because it applies to reading and writing fiction:

I think I would agree that all Christian writers need not feel they must specifically include the Gospel start-to-finish to qualify as a “Christian novel.” Not even the books of the Bible do that. However, for Christian writers …

We now do have the complete Gospel. It makes sense to include most of it and base more of our fiction on it and its effects — very few are doing that now!

By contrast, we seem already to have plenty of common-grace-style echoes of God’s truth: in secular stories, sunrises, nature, existing Christian fiction, and more. I’d totally agree that Christians should not discount those ways God communicates; arguing that Scripture is sufficient isn’t necessary because valuing God’s “general” revelation in nature doesn’t rule out His specific revelation. However, Christians have more to offer than that. Why only echo general revelation when we can one-up it?

Becky,

I agree that Lewis and Tolkien were firm in their belief in who God was, but there beliefs about what that God was differed greatly. Differences between Catholics and Protestants are not small differences, though perhaps it would be better if they were.

I think a novel can say profound things about God without neccessarily mentioning him often. And I think it can say profound things about him while mentioning him a lot. What it can’t do is make the “mentions” artificial or unnatural in the course of dialogue, which is a tendency of many Christian writers, including this lib Christian at times. From the samples of writing I’ve seen on this site and its affiliates, I think it’s a problem many Christian writers have. Doing realistic “God dialogue” is hard, which is why I think Christians should tend to avoid it till they can do it effectively. Look at the power of James Baldwin’s Go Tell it On the Mountain, a novel filled with “God talk”, but where it never seems out of place. Frankly, some of the best Christian writing is being done by non-Christian writers. There’s not a Christian sci-fi novel in the current market that matches what Orson Scott Card did in Speaker for the Dead, for instance, particularly the parablic elements of that great novel.

I agree with Adam that Leland Ryken and some of his contemporaries in the Reformed movement have made some progress in creating an effective evangelical literary aesthetic, but a lot of work has to be done. Schaeffer, in particular, tends to reject artistic methods solely based on whether he likes them or not – thus he throws out almost all of modernist art and writing. I’m not a big fan of modernism, but I think that’s ridiculous. The world would definitely be spiritually impoverished if we lost Mrs. Dalloway or The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. I think, as I’ve said to Chris Walley before, that fundamentalists are actually far more artistically consistent and thought out than the Reformed movement. They see art (usually) as a bad thing, and that’s actually in line with some pretty advanced arguments from people like John Carey (What Good Are the Arts?) and Duchamp, with his famous urinal artwork, which challenged whether art was even a meaningful category. I think we must consider the possibility that born-again Christians can simply not create good art, and may not be meant to, because the worldview behind modern aesthetics is so antithetical to the evangelical worldview. I don’t think that makes evangelicals inferior, or stupid, it just means we have to recognize our strengths. I think there are therefore two fundamental questions:

1. Should Christians even be interested in art? Is art antithetical to the Christian worldview? Remember how much art has been used to abuse people. The most famous artist of the twentieth century was Adolf Hitler and look what he did. Check out the documentary Architecture of Doom if you don’t think Hitler’s artistic views influenced his politics

2. If there is such a thing as Christian art, what should its boundaries be (if any)? I personally do believe in artistic boundaries, because I can’t agree with Nabokov-lovers that a well made snuff film is art. Yet, in my own art, I try to come up with outrageous situations every day, so perhaps I’m somewhat contradictory. And again, art having a moral center may be antithetical to good writing. That’s something that also needs to be discussed (though I concede that there are some authors who are also good moralists. I’m just not sure if they’re good because of their moralizing, or in spite of it).

Some big questions, John.

I agree with you, certainly, that we don’t depict God realistically by including Him more … or less, in our stories. It isn’t about the amount of face time. It’s about the kinds of things you are talking about. On my site, in one of his comments, Fred said I was wanting a “gritter” depiction of God, and I think that’s so.

Interestingly, some people complain about God, saying that if He were really all powerful, He’d step in and stop evil. But when He did so, as recorded in the Old Testament, bringing an end to morally corrupt, degenerate, and violent nations, many of the same people are upset that He act in such a wrathful way.

God is a just judge, and yes, that means He makes the hard call at times. And why don’t we want to put that in our stories? It’s truthful. If I start from a position of truth, then I shouldn’t hesitate to start with God’s nature and speculate from there. What would a just, righteous, good, sovereign king look like to his subjects, for example.

More later. Busy day today. But thanks for interacting with the post so thoughtfully, John.

Becky

But I’m getting off track. I wanted to address the idea you brought up: Is art antithetical to the Christian worldview? I’d say, operating on the definition that art is an expression of truth and beauty by the utilization of both beauty and truth, then the Christian is the most qualified to create art. Now if you take the truth component out, or if you define beauty as that which is beautiful to the beholder, the Christian will reach some point where he cannot go.

But part of what I’m trying to point out is that every secular writer has places he cannot go, too. He does not know God and cannot explore His true nature or plan or work. He simply remains ignorant and left to his own speculation will get it wrong one hundred percent of the time. His sinful mind is darkened and he cannot see.

So we throw these accusations at Christian writers — that something is lacking in their writing — but we praise secular writers who also have something lacking in their writing.

I’ll say again, I believe we should strive to get both beauty and truth right. I don’t think some of the novels you reference as poor art are getting either right. I’ve read some stories that are poorly written and have said nothing truthful about God (or nothing about God at all really, though they have included some sort of “faith element”). There are others that actually do include truth to a certain extent — not a preachy, one note, shallow treatment of God. There are a few that are moving toward beauty in their writing. Then there is a small number that actually achieve both.

I don’t see the number in that later group increasing greatly as long as we’re using the discovery method.

Some big questions, John.

I agree with you, certainly, that we don’t depict God realistically by including Him more … or less, in our stories. It isn’t about the amount of face time. It’s about the kinds of things you are talking about. On my site, in one of his comments, Fred said I was wanting a “gritter” depiction of God, and I think that’s so. My comments in black throughout. I don’t mind a grittier depiction of God, even if it goes against my own theological proclivities, so long as that portrayal takes its own preconceptions to their logical conclusion. As I’ve said before here (to raucous laughter, I know), that’s why I and many other people on the left have a respect for people like Jack Chick or James Baldwin, even when their image of God is terrifying to others (Baldwin’s God had a big problem with white people, among other nemesises, not that I blame the man). It’s also why I respect Frank Peretti, though I’m not sure he’s a particularly good writer in secular or non-evangelical terms. Peretti does not pull punches about any unpopular part of the Bible, including those parts unpopular to evangelicals (like some of the parts I mentioned to Steve). But evangelical fiction reads like cotton candy theology – either preaching to the choir, a la Alcorn, or creating warm fuzzy theological figures like the Veggie Tales. You won’t find great art either way there. Not that I think great art should neccessarily be the goal of evangelical literature. I just think evangelicals should be honest that it’s not the goal, or that what constitutes great art to evangelicals should be judged by a totally different standard than the rest of the world (which I’m also o.k. with)

Interestingly, some people complain about God, saying that if He were really all powerful, He’d step in and stop evil. But when He did so, as recorded in the Old Testament, bringing an end to morally corrupt, degenerate, and violent nations, many of the same people are upset that He act in such a wrathful way. I’m not saying whether I’m upset or not, I’m just saying evangelicals are inconsistent here. There are plenty of extra-biblical commandments that evangelicals have attached on to the Bible that have no basis in it. Abolitionism, commands against polygamy, etc. Even the Biblical justifiation against pedophilia is only based on one verse (which I thank the Lord is in there!).

God is a just judge, and yes, that means He makes the hard call at times. And why don’t we want to put that in our stories? It’s truthful. If I start from a position of truth, then I shouldn’t hesitate to start with God’s nature and speculate from there. What would a just, righteous, good, sovereign king look like to his subjects, for example. There’s no problem here, so long as the artist is trying to depict the universe as authentically as they can. The problem comes when evangelicals don’t the put same eye to their own culture that they do to the “world’s” (and I’ve read some secular fiction about evangelicals that makes the same mistake).

More later. Busy day today. But thanks for interacting with the post so thoughtfully, John.

Becky

But I’m getting off track. I wanted to address the idea you brought up: Is art antithetical to the Christian worldview? I’d say, operating on the definition that art is an expression of truth and beauty by the utilization of both beauty and truth, then the Christian is the most qualified to create art. Now if you take the truth component out, or if you define beauty as that which is beautiful to the beholder, the Christian will reach some point where he cannot go. I definitely don’t think art is truth, and I don’t think many of the church fathers, the disciples, or Christ would have posited that, though they certainly would have argued that art could convey truth. What do you mean by beauty? Both of these terms are highly subjectie (I’m not saying relative, I’m just saying you’re not doing a good job defining them. No offense intended). Are you talking about “T”ruth or “t”ruth. I don’t think every artwork has to convey a Christian message to be true. Indeed, some works, antithetical to Christianity, may actually enrich our faith more than works that support it. For instance, Tom Jones, a very bawdy 18th century fiction novels, teaches more about proper Christian character than I ever learned reading Pat Robertson’s End of the Age or anything by the venerable Schaeffer.

But part of what I’m trying to point out is that every secular writer has places he cannot go, too. He does not know God and cannot explore His true nature or plan or work. He simply remains ignorant and left to his own speculation will get it wrong one hundred percent of the time. His sinful mind is darkened and he cannot see. I agree that there should be boundaries to art. I disagree that secular writers cannot know God and explore his true nature. If that was the case, good evangelical works would outnumber secular ones. That is obviously not the case. Furthermore, most of the evangelical novels that are good – Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Jane Eyre, Robert Falconer – were written by evangelicals whose theology would be considered suspect today (all of those popular examples of great evangelical art were written by universalists, which I have to say, completely trounce conservative evangelicals in well written fiction up to Leif Enger)

So we throw these accusations at Christian writers — that something is lacking in their writing — but we praise secular writers who also have something lacking in their writing.

I’ll say again, I believe we should strive to get both beauty and truth right. I don’t think some of the novels you reference as poor art are getting either right. I’ve read some stories that are poorly written and have said nothing truthful about God (or nothing about God at all really, though they have included some sort of “faith element”). There are others that actually do include truth to a certain extent — not a preachy, one note, shallow treatment of God. There are a few that are moving toward beauty in their writing. Then there is a small number that actually achieve both.

I don’t see the number in that later group increasing greatly as long as we’re using the discovery method. And I think your method will just create theological heresy-hunting, as it does on this site (again, no offense). You can have great art, you can have great theology, but in evangelicalism I don’t think you can have both. Not because evangelicals are dumb. They aren’t. Not because they’re evil. They aren’t. No, because evangelicalism has always had a concern with helping people in the here and now, whether that help is through the salvific gospel or the social gospel. What evangelicals are not good at doing is building Vatican Basicallas and Catholic paintings. Why would we want to imitate that? With all respect to Catholics, the overabundance of such material in the RCC has led to the material corruption of its hierarchy and the impoverishment of its laity. Evangelicals have a better gospel to give than that, whether they choose the left or the right.

John, unfortunately I don’t have time to debate these issues. We are obviously coming at the subject from different perspectives. I do have to remark about this line, though:

😆 I’m curious how you think theological figures written for children should appear.

My biggest point of contention, however, is with the idea that those who do not know God can write truthfully about Him. That defies logic, John.

Becky

Becky, not to take the conversation too far off topic, but I think another problem with portraying God “realistically” is that Christian fiction equates realistically with predictably, in order to create a nice, neat God who fits into Lee Stroebel apologetic manuals and Ravi Zacharias crusades. The God who asks for a child sacrifice (Jesus, Isaac) and calmly orders genocides left and right, with bashed in baby brains, is conveniently forgotten, both by evangelicals and by many liberals. Nobody’s consistent here, nor is Jesus’s threat to send all rich people to hell taken very seriously, which would certainly mean that Randy Alcorn would not pass through the pearly gates, at the very least (have you read what the guy’s written guys- I mean seriously “rape crisis centers are lesbian recruiting grounds” – how sick does a guy have to be to be quoted on this site?).

I think Christian fiction, like Ayn Rand novels, suffers from the terminal error, that one can predict which characters are “good” and which “evil” by page 3 (barring those who will get converted in the last 1/3rd of the novel). It’s why people can’t stand Rand, and it’s why she’s considered a poor writer. Good fiction, even when these characteristics are delineated, usually gives us complex moral characters – Hamlet, Othello, Dorothea Brooke. The problem with much Christian fiction is that it follows Lewis and Tolkien’s rather simplistic characterizations, without ever using the handful of complex characters these authors would always invent to make their works have some weight. Imagine Lord of the Rings without Boromir, Saruman, Gollum, or Frodo, for instance. Imagine the Silver Chair without Puddleglum (the book would literally be unreadable). And in some cases, the author invites us to explore the minds of very evil characters, like Alec in Clockwork Orange or Humbert Humbert in Lolita, not out of voyeurism, but out of a desire to understand, or alternately a desire to simply create a great work of art. Kubrick’s Clockwork has a woman being raped to “Singing in the Rain”, yet the commentary the film makes on male violence through that depiction is chilling and powerful. It is only when such subjects are not treated with deep thought, such as in Samuel Richardson’s Pamela (sorry guys, I hate it), that I find the writing objectionable.

John, I’ll read the rest of your comments soon, but you’ve flagrantly distorted God here:

You seem to have confused a Psalmist’s desperate cry for justice with the “God is mean” accusations.

And just where exactly did Jesus say that? 😉

Without clarification — which I’d be glad to hear! — it sounds like another version of the tired old myth “Jesus credited the Poor with some special virtue and said rich people were worse.” It misses the clear point of Mark 10: 23-27.

No statement here about Things being evil. That’s creeping Gnosticism/asceticism. The point is that even the “best” people, as the disciples perceived, the most “religious” people with wealth and thus time to do good works, cannot get into the Kingdom. But “with man it is impossible, but not with God.” Only God working supernaturally can get the “best” people into the Kingdom.

Not sure how one gets from that to “Jesus’s threat to send all rich people to hell.” I’d highly recommend a re-evaluation! 🙂 Perhaps this will help, at YeHaveHeard.

As for Randy Alcorn, I’m afraid you may be less happy with us, by this month’s end. 😉

Stephen,

Last I checked, you hadn’t been elected the Protestant Pope, but hey, lol.

Anyway, who said God was mean? I’m just saying who he is not neccessarily the fuzzy God of liberalism nor the mostly fuzzy materialist God of evangelicalism

Matthew 25 is all the proof I need about who Jesus believed was going to hell whatever fresh interpretations have been placed on his words over the last two millenia. And if Jesus did not credit the poor with some special virtue, then how does one explain the Beautitudes. I’m sorry Steve I’m just not interested in another theological debate with you where you assume your opinion is superior because it’s considered more orthodox by born-again Christians (I know you wouldn’t see your opinion as resulting from those factors, but from the outside, that’s what it looks like).

33 He will place the sheep on his right and the goats on his left.34 Then the king will say to those on his right, ‘Come, you who are blessed by my Father. Inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world.35 For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, a stranger and you welcomed me,36 naked and you clothed me, ill and you cared for me, in prison and you visited me.’37 Then the righteous 16will answer him and say, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you drink?38 When did we see you a stranger and welcome you, or naked and clothe you?39 When did we see you ill or in prison, and visit you?’40 And the king will say to them in reply, ‘Amen, I say to you, whatever you did for one of these least brothers of mine, you did for me.’41 17Then he will say to those on his left, ‘Depart from me, you accursed, into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels.42 For I was hungry and you gave me no food, I was thirsty and you gave me no drink,43 a stranger and you gave me no welcome, naked and you gave me no clothing, ill and in prison, and you did not care for me.’44 18Then they will answer and say, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry or thirsty or a stranger or naked or ill or in prison, and not minister to your needs?’45 He will answer them, ‘Amen, I say to you, what you did not do for one of these least ones, you did not do for me.’46 And these will go off to eternal punishment, but the righteous to eternal life.”

Yeah y’are; otherwise you wouldn’t have commented! Let’s admit we both enjoy it. 😉

I do believe “my” views (actually given to me by others) are accurate here, and so far you haven’t tried to challenge my exegesis of Mark 10: 23-27. Whether I think I’m right or you think you’re right doesn’t matter. What is truth? To claim to have one piece of it is not the same as claiming to have all truth. That’s a hackneyed ad hominem charge that doesn’t help and assumes the worst of someone else in an unloving way.

Ha ha ha ha ha! Again, both you and I have been claiming to have a piece of truth and that doesn’t mean either of us has claimed to know all truth.

What did you think of the above exegesis of Mark 10: 23-27?

Agreed. I’d add that He also isn’t a fuzzy “God is ‘love’ as defined by what I think love means.” (By the way, I also thought later to clarify that yes, absolutely we need to wrestle with the truth that God does and will kill people and be perfectly right to do this. My main point is that it’s not helpful to Christians or others to call this “genocide.”)

Do some searching for Martin Lloyd Jones’ discernment on how Jesus showed the real point of the Law in the whole Sermon on the Mount and promoted an ethics of Kingdom citizens that are impossible for normal, unregenerate people to follow. That’s the point of the Beatitudes — not that we walk away with a new to-do list of behaviors to emulate, but knowing that we can’t be this way on our own — not without Christ.

But let’s focus, if you wish to continue. Rather than jumping into other passages (or treating one part of the Bible as more important than other), what do you think of Mark 10 and what Jesus was actually saying about wealthy people? If He meant corporate fat-cat types, why were the disciples astonished at His words? If He was really threatening all the “rich” with Hell, how come He went on to say “all things are possible with God,” meaning that with God, even rich people could get into the Kingdom?

Remember a cardinal rule of reading everything, especially Scripture: a passage can’t suddenly mean now what it never meant then. I haven’t read you that way, and I certainly hope you won’t read my material that way either! 😀

Thanks for an intriguing discussion.

Stephen, I’m not getting into this debate. I meant what I said. I want to talk about art and theology, not get sidetracked into another endless debate with you in which you question my Christian belief.

John, you said something that can be proved, by anyone simply reading the Scripture — a surface-level, without need to get into Art and Theology — to be untrue.

It seems you seem to want a free license to question my beliefs, which no robust (or humble!) Christian should take offense to, but balk when the same ethic is practiced against you. How come? Do you truly believe you’re above having your beliefs questioned and challenged? Perhaps if this were personal and not online-only, if we were friends in other ways (which we could be, due to our mutual interest in Christian visionary fiction!), that would help. Maybe I’m also coming across as nothing but a troll; I’m not sure.

I have my Christian beliefs questioned all the time. Sometimes I’m right and it’s the critic who’s wrong, and clearly has an agenda apart from Scripture. Sometimes I’m wrong and need to rethink my position on things. But either way, no one ever grows out of listening and learning and re-evaluating, not based on some imagined subservience to the questioner, but based on allegiance to God and what He’s revealed in His Word.

If it were just opinions at issue here, I could understand the annoyance … but it’s about Truth, isn’t it? Moreover, how can one truly discuss Art and Theology while retreating from serious challenges? How would anyone grow in both humility and knowledge?

I hate people who quote Proverbs moralistically (don’t you?). So it’s not in that spirit, but in the hope that humility in the Gospel is the clear context, that I cite these verses:

Meanwhile, from Becky‘s comment, above:

Fascinating! I hadn’t considered it that way before, so directly. 😀

Stephen, I just read in Exodus 17, I think it was, about the Amalekite people attacking the escaping Hebrews. I think it would be fair to assume these former slaves weren’t particularly armed for combat. And God had purposefully led them away from potential conflict because he didn’t want them discouraged by such adversity.

We don’t have recorded in Scripture any direct command from God to the Amalekites that they should not attack, but His response certainly gives the impression that they were violating His will.

The point is, that’s a perfect example of the point above. How would we react if this was on TV: Helpless refugees fleeing oppression, attacked by waring profiteers. Details at eleven. Would we think twice about sending in help for the refugees?

Just to be clear, it is these same Amalekites who Saul was ordered to defeat utterly. They had had all those years between Moses and Saul to repent and turn from their evil actions, and they didn’t. Judgment day came, and Saul was to be the instrument God used to fulfill what He said to Moses all those years earlier.

The story actually portrays God’s long suffering more than it does His wrath.

Yet some might think of all the harm the Amalekites may have done in the intervening years. And we’re right back to people hating God for not stepping in and putting a stop to them sooner.

Becky

John, you said something that can be proved, by anyone simply reading the Scripture — a surface-level, without need to get into Art and Theology — to be untrue. But as I’ve explained before, we don’t read the Scripture the same way, and you’ve never given me a convincing explanation why your method of reading scripture, with its nearness to biblical literalism, should be preferable.

It seems you seem to want a free license to question my beliefs, which no robust (or humble!) Christian should take offense to, but balk when the same ethic is practiced against you. How come? Do you truly believe you’re above having your beliefs questioned and challenged? Perhaps if this were personal and not online-only, if we were friends in other ways (which we could be, due to our mutual interest in Christian visionary fiction!), that would help. Maybe I’m also coming across as nothing but a troll; I’m not sure. I don’t want my faith in Christ questioned, that’s all. I don’t question your faith in Christ, I just question your logic and your interpretative strategies.

I have my Christian beliefs questioned all the time. Sometimes I’m right and it’s the critic who’s wrong, and clearly has an agenda apart from Scripture. Sometimes I’m wrong and need to rethink my position on things. But either way, no one ever grows out of listening and learning and re-evaluating, not based on some imagined subservience to the questioner, but based on allegiance to God and what He’s revealed in His Word. Again, I’m not a literalist, so this does not mean anything to me.

I do see you basically as a troll, which is why I try to avoid conflicts with you.

John, why can we not be friends?

My intent in pointing out inconsistencies is not to smash you down or elevate myself. Rather, I’ve seen Scripture that challenges my own pride in my own supposed worldly wisdom, and personally experienced the benefit of listening to others and adjusting my beliefs to fit God’s truths as found in His Word, which others may echo (even if accidentally!).

Here’s one very honest example! One of my (very sinful!) instincts in response to your recent comment is to go all sarcastic on you, and instead of trying to respond with Christlikeness, come out with guns blazing and bursting out sarcasm bullets. I could blame the Internet, or Our Sarcastic Age, or mass media, or whatever — instead, I have only to blame myself and the fact that even as a Christian, the Spirit is still changing me from the outside out, as I work with Him! How do I know what He wants? A “literal” reading of Scripture (more on this in a moment). It constrains me, and, I hope, keeps me from the trollish behavior that I do see often on the internet (though, I hope, avoid).

In that spirit, if you can show where I have actually questioned your “faith in Christ” (your words) instead of simply “your logic and your interpretive strategies” (your words about your challenges to me), I’ll gladly correct it.

So far, though, I have not seen where I’ve done that. You seem to have practiced your own professed method of “interpreting” Scripture on my words as well, reading between the lines to try to discern my “real” motivation. I’m not picking on that or saying it’s inconsistent; in fact, it’s very consistent to read everything “nonliterally”! Instead the inconsistency arises when you expect to be read “literally” yourself. I could easily find many ways you and I actually agree, if I practiced the same mode of “interpretation” on your own writings.

You may recall from our previous lengthy interaction my contention that the people who practiced all kinds of wrongs against you — anti-Semitism, demon “exorcisms,” etc. — were abusing Scripture, ripping it from context, ignoring the original meanings — to salvage for their own spiritual systems. I’ve challenged you to consider why you’re doing the same thing. Otherwise any discussion here, with mutual exchange and learning, is constrained and limited. In effect you would end up saying: I’ll talk about anything, but only on a surface level; my presuppositions are off-limits for questioning, and you must “give me a convincing explanation” for your own root beliefs according to the rules of my core beliefs.

So noted! But again I ask you to show where I have questioned “your faith in Christ,” rather than also “your logic and interpretative strategies.” It seems when I do question those, you’ve claimed I’m therefore questioning “your faith in Christ.” A result of the “nonliteral” interpretative strategies, perhaps? If so, my assumption is that it’s not deliberate on your part. I’ve been in many discussions with people in which — rightly or wrongly — I assumed they didn’t really want to go deep with their questions, but were only seeking a fight for the fun of it, and therefore I got preemptively defensive.

That’s why I said what I said about meeting on common ground. This site, though, and its basis, would seem to be that common ground.

Which gives me a chance to ask, again, what you mean by “literalist.”

Just now, I read your paragraph “literally.” By that I mean that I sought to understand your original intent, out of respect for you to have an opinion and express it well, even though I haven’t met you. Your first sentence is more “literal,” in the most rigid sense of the word; in your next sentence, though, you called me a “troll.” Here I also read that “literally,” in a sense, though not in the wrongful, rigid definition of “literalism” that would have you actually calling me an ugly mythological creature. Instead I applied the common definition of “troll,” in the cultural context of the internet: someone who just argues for the fun of it and to rouse some rabble. That’s what I mean by literal reading — seeking the author’s original intent, mindful of cultural context and metaphors.

So I wonder if that’s what you mean by “literalist” as applied to those who read Scripture “literally.” As I’ve asked before, are you by accident confusing definitions and granting the verse-abusers and context-ignorers the benefit of the doubt when they “read the Bible literally” and ignore cultural context, what the material meant to the original hearers, and metaphors and such? But if, as you’ve said, such people wrongfully abused you and violated Scripture, why suddenly believe they’re giving you the right definition of “literal reading,” which you now seem determined to avoid (but only with Scripture)?

I may also ask: what could I do to help you feel more comfortable with discussing your presuppositions, definitions of terms, and Scripture-reading methods, without provoking a defensive (perhaps instinctive) desire to protect yourself from harm?

By the way, it’s a bit difficult for me to “troll” on a website that I co-sponsor. 😉

Stephen, only in part am I referring to common grace. I could happily subscribe SpecFaith’s belief statement, though I don’t particularly like the “sometimes” when referring to unbelievers stumbling onto truth. In fact, many unbelievers understand great truths, in part. In Genesis, it is not the faithful but the unfaithful that develop instruments, weapons, cities, tools, agriculture and so on (Gen. 4:20-22). The NT tells us that all we receive, including all ideas, wisdom and knowledge is a gift (John 3:27) given from Christ to mankind (Col. 2:3). The OT tells us that Christ Himself teaches them these things directly, though they do not recognize Him (Isa 28:23-28). So when Christ came and gave the gift of modern art on some unbeliever, it wasn’t a blind stumbling sort of occasional thing.

But I’m not specifically talking about that. I took from your comment that you understood me to saying that we can include less than the full gospel in our stories. This is certainly true, but not really what I was trying to get at. Likely this is my fault, because I’m trying to think about and develop a large idea out loud!

No, if you but glance at my blog, you will see that I’m very interested in communicating the gospel in my stories. Almost everything I write about writing and stories is very obviously built on the gospel. I want the total gospel and the gospel totally in my work.

I suppose what I’m really getting at is this: how is the gospel communicated? How does the Bible communicating meaning to us? Not through abstract propositions. The epistles of Paul are generally an anomaly in that they read like philosophy and theology papers. But if we want to look at how God communicates truth to us, the fact is that the majority of the Bible is mostly stories and symbols and descriptions of tables, chairs, buildings. We have theology textbooks filled with concepts like propitiation, sanctification and common grace; the Bible is filled with concrete things like hair, oil, water, blood, unclean issues, animal sacrifice, and so on. The Bible communicates meaning to us through structural parallels and symbolism. It communicates on a deeper level and doesn’t really tell us much about what things mean; we are expected to put in the time, read it over and over and gradually we’ll see patterns and shapes start to emerge.

One of my favorite “for instance”s: When Peter denies Jesus three times, he does so standing around a coal fire. When he gets to the house of the High Priest he is said to be “following Jesus,” but then he stops following Jesus and hovers around the coal fire with the disciples of another. Typologically speaking, Jesus is the New Moses, and Peter the New Aaron. This is, then, is Peter’s “golden calf” moment, and just like in Exodus, Yahweh departs and pitches His tent elsewhere (in transferring covenant status from Israel to the Church in His death). Then, in John 21, Peter is gathered by Jesus around another coal fire with God’s true disciples, and Jesus tells him three times to “feed the sheep.” Is any of that apparent? Not really; it takes reading it and holding all the previous stories in your head when you come to a new one.

So really what I’m talking about is writing books Christianly on this level. We tend to think metaphor and symbolism are superficial, arbitrary, or otherwise an adornment over top of reality. But they are actually the principle way in which God communicates. I have written about this.