‘The Hobbit’ Story Group 4: Over Hill and Under Hill

Reviews for The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey film are rolling in, and too many reviewers have little clue what they’re talking about, regarding The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings.

Variety tries to contrast The Hobbit’s three-part film division with The Lord of the Rings: “Whereas ‘The Lord of the Rings’ naturally divided into the three books …” No. Untrue. The Lord of the Rings is a single story, divided into three printed installments. Each one of those contains two sectioned “books” apiece, actually yielding six episodes. Yet it’s a single story.

Next thing you know, Variety may call The Lord of the Rings a “trilogy” — though to be fair, even the backs of LotR paperbacks refers to the “trilogy.” The publisher’s website is called LordoftheRingsTrilogy.com, and (as of this writing) graphics there also refer to a “trilogy.”

The Variety review also refers to “the troll-infested forest of Mirkwood.” We could suggest that is from the film — except that film 1 will end before the heroes even enter Mirkwood.

The Hollywood Reporter isn’t much better in its review’s reference to “repulsive trolls who give chase on ferocious, wolf-like wargs.” Not only the book but the film’s trailers clearly show goblins riding wargs. From whence comes these confusions of goblins and trolls?

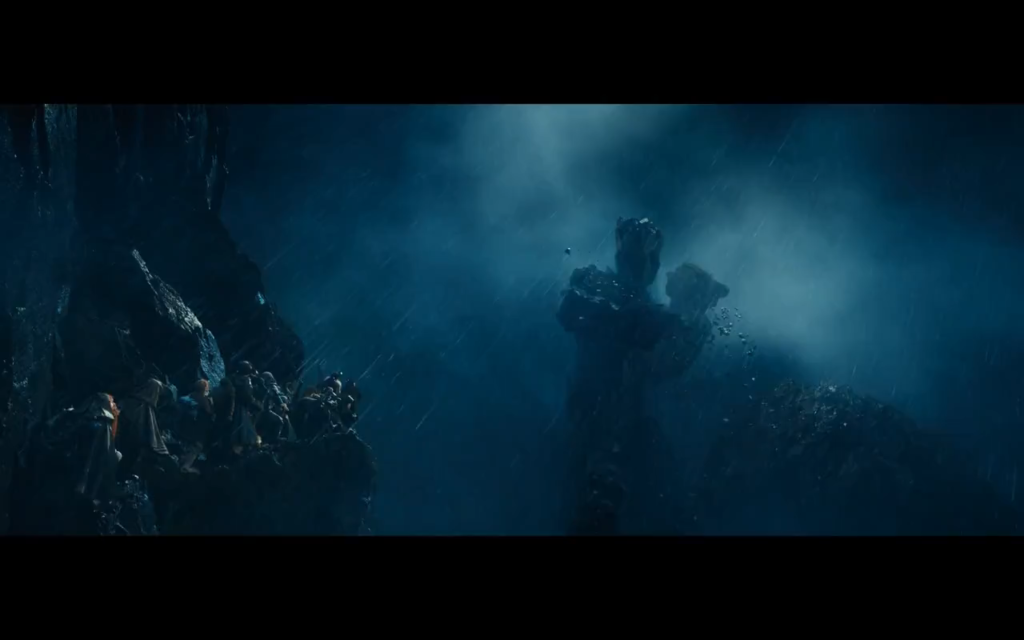

“[Bilbo] saw that across the valley the stone-giants were out, and were hurling rocks at one another for a game, and catching them, and tossing them down into the darkness […]”

- Great southern deserts and tribes.

- “Stone-giants” (specific to this chapter).

- Joyful Elves who sing “tra-la-la-lally” from treetops.

- A talking purse that gives away burglar-in-training Bilbo.

- An axiomatic, no-backstoried character called “Tom Bombadil.”

- Werewolves (though not the familiar shape-shifting human kind).

For the Lord of the Rings film trilogy (okay, we can call that a “trilogy”), the adaptation removes Tom Bombadil, and few complained. I similarly expected The Hobbit to remove the book’s brief mention of stone giants. Yet what did we see in the second trailer? Nothing but smashing stone giants, looking like the mineral equivalent of Treebeard and the Ents!

What else about The Hobbit, especially in this chapter, seems so different from The Lord of the Rings? How does that strike you? Do you hope for more or less difference in the films?

Chapter 4: Over Hill and Under Hill

- Read chapter 4, from the beginning to quarreled over by goblins (page 58).

- Boulders, too, at times came galloping down the mountain-sides (page 53). Why do you think Tolkien here says “galloping”? Why not “falling”? What images come to mind with each? Have you ever written a story and thought to use one word rather than another?

- Dwarves had not passed that way for many years, but Gandalf had, and he knew how evil and danger had grown and thriven in the wild. … Even the good plans of wise wizards like Gandalf and of good friends like Elrond go stray sometimes when you are off on dangerous adventures over the Edge of the Wild; and Gandalf was a wise enough wizard to know it. (page 54) How does this increase suspense? Why mention specifically that it is Gandalf who is nervous about the dangers? How might increasing dangers make other stories, including our real-life stories better or more interesting to tell when they’re completed?

- [… Bilbo] saw that across the valley the stone-giants were out, and were hurling rocks at one another for a game, and catching them, and tossing them down into the darkness … (page 55). Stone-giants in Middle-earth! And barely a mention. Does that seem odd?

Why do you think Bilbo has a bad dream that, in part, turns out to be real? As with the stone-giants, this goes unexplained. Do you like or dislike not knowing the explanation? As Christians, do we accept or struggle with unexplained, seeming “magical” moments?

Why do you think Bilbo has a bad dream that, in part, turns out to be real? As with the stone-giants, this goes unexplained. Do you like or dislike not knowing the explanation? As Christians, do we accept or struggle with unexplained, seeming “magical” moments?- How do the goblins strike you? What do you imagine? Do they seem frightening?

- Read chapter 4, from I am afraid that was the last they ever saw of those excellent little ponies (page 59) to the chapter’s very end.

- Why do you think Tolkien that the goblins make no beautiful things? Who are they unlike, then? Why might he even imply they make our world’s weapons (page 59)? Unlike in The Lord of the Rings and other stories that are clearly set in other magical worlds, why might he in this story keep suggesting that it’s part of our world’s history?

- Does Gandalf’s arrival and rescue seem expected? If you’ve heard of the idea of a Deus ex machina ending (a god or hero appears at the last moment to save everyone, which is somewhat boring), does that seem to apply here? (Hint: what actually happens next?)

How do you like the battle scenes? Which sorts of responses do they stir within us?

Chapter 4 is probably my favorite chapter in the whole book, and this post brings up some great points about it.

Maybe that’s only sloppy journalism. I wonder if the Hobbit movies are going to do anything more with Mirkwood than the immediate plot of the Hobbit book exposes. Dol Guldur in southern Mirkwood is an evil place, and I think stuff is happening there during the time that Bilbo and the dwarves are traveling. Gandalf is certainly busy for the portions of the story in which he’s away from the company. Maybe there could be a legitimate way to put trolls in Mirkwood, by cutting away to the canonical references of what’s going on in Dol Guldur, as long as they’re not messing up Bilbo’s story line.

The stone giants have seemed odd to me in the past. Once, reading a forum online without the text in front of me, I agreed with an argument that they were only metaphors that Tolkien was using to describe the storm, or else figures of Bilbo’s imagination. But now I see that that can’t be. They’re real, and the dwarves talk about them.

I don’t think it should feel odd to us, though. Although Tolkien pretty much started the expectancy of realistic, meticulous worldbuilding in speculative fiction, Tolkien’s worldbuilding is still as mysterious as it is thorough. Maybe the Hobbit emphasizes the mystery more, but it’s there in The Lord of the Rings, as well. Why should we expect even Tolkien to know everything about his sub-creation, let alone tell us everything that he knows? The mystery makes it more real, as well.

This is a step toward Bilbo’s eventual finding of the Ring, which in turn is a step toward the Ring eventually being destroyed and the world saved from its evil. This may be the best way that Tolkien mirrored reality. We don’t know the answers, but it all works together. There is both destiny and Providence in Tolkien’s world, even though good people very often do suffer.

I don’t know what you are asking. Are you referring to “magical” moments like this in fiction? If so, I can’t think of any possible difficulty! Even if a Christian reader were worried about witchcraft, there would be no possible concern for this passage. This is not explicit “magic”; there is a little of that later in this chapter, when Gandalf saves everyone from the goblins. But this is only “magical” in the Narnian sense. This is a powerful Christian theme, to me. We don’t know why Bilbo had a premonition, but we know that nothing happens without a purpose, including the misfortune of Bilbo and the dwarves being captured in the first place.

This is one of the best and clearest depictions of orcs and their dark society in Tolkien’s writings, I think. Although they are savage and terrifying, I think they are treated with a shred of humanity, too. They’re monsters, but they’re sentient human monsters. (Technically, they are mutated descendants of elves.) Maybe Tolkien meant us to hate them, but I think he meant us to see the worst of ourselves in them, too.

For one, they are opposite to the dwarves, who love to make beautiful things, and love beautiful things that were skilfully made.

I think this raises one of the topics that has been discussed here. The goblins have real skill at craftsmanship, and they use it for evil purpose.

It allows us to see the goblin society as a picture of our modern industrial world. Like the industrial world, the goblin society is ruthlessly efficient in their construction, but they are blind to beauty and do not understand the honor of making something with one’s own hands.

Gandalf is the best deus ex machina ever to grace the pages of literature. 😉 I’m not sure what you’re implying with the hint. Could you clarify?

This is a great post. I’m sorry I didn’t comment sooner; I was busy with finals.