What Makes A Villain?

Hey, everyone! I hope you all had a great Thanksgiving! I know I missed my last post. I blame the tryptophan from the turkey.

Wait . . . I hadn’t eaten any turkey on Wednesday . . . Yikes! Better keep going!

If you were here a month ago, you’ll remember that my last post was pretty short, just a quick question about who the greatest villains were. I don’t know why, but I’ve had villains on my mind lately. Maybe it’s a hazard of writing superhero stories. But this week, I started thinking about a slightly different question: what makes a villain a good one?

If you were here a month ago, you’ll remember that my last post was pretty short, just a quick question about who the greatest villains were. I don’t know why, but I’ve had villains on my mind lately. Maybe it’s a hazard of writing superhero stories. But this week, I started thinking about a slightly different question: what makes a villain a good one?

I can remember many, many years ago, while I was still in high school, that I got into a conversation with a student teacher in my school about Frank Peretti’s angel books. I don’t remember everything she said about them, but I do remember that she didn’t like the female New Age guru in This Present Darkness. She thought that this obvious bad guy was cartoonish and unrealistic.

We’ve probably all heard the dictum that everyone thinks they’re the hero of their own stories. While people may do horrible, evil things to one another, very few of them do so because they’ve devoted themselves to the practice of evil villainy. When authors and storytellers remember that, their “bad guys” become even more compelling.

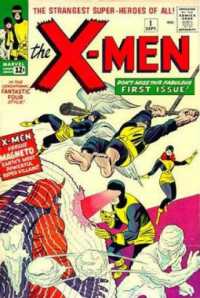

Take Magneto, the “big bad” who faces off against the X-Men. When Magneto was first introduced in the ’60s, there was little nuance to his character. He was a bad guy, pure and simple, dedicated to death and destruction. This is the guy, after all, who put together a team of people and named them, without a hint of irony, “The Brotherhood of Evil Mutants.” With a name like that, you have to wonder who would seriously sign up!

Take Magneto, the “big bad” who faces off against the X-Men. When Magneto was first introduced in the ’60s, there was little nuance to his character. He was a bad guy, pure and simple, dedicated to death and destruction. This is the guy, after all, who put together a team of people and named them, without a hint of irony, “The Brotherhood of Evil Mutants.” With a name like that, you have to wonder who would seriously sign up!

But over the past few decades, Magneto’s character has evolved beyond that. Now he’s an almost sympathetic figure, a man who has dedicated his life to fighting for the superiority of mutants. We saw that in the recent X-Men movies. Magneto starts as a survivor of the holocaust, someone who saw his people being wiped out by those who feared them. It’s easy to understand why Magneto would resort to extreme measures to protect his fellow mutants from meeting a similar fate. Now Magneto is a complex, rich character, one that people can sympathize with and maybe even wonder if he’s somehow in the right. That’s good storytelling.

But at the same time, though, I’ve recently come to realize that sometimes, deconstructing a villain’s motivation actually hurts them and makes them less effective as agents of evil.

Take the Reapers in the Mass Effect video game franchise. For those unfamiliar with the story in this fantastic game series, you play as Commander Shepard, a human military officer who finds him- or herself in the midst of a crisis of galactic proportions. A race of sentient machines as large as starships called the Reapers will soon return to the galaxy and destroy every advanced civilization they can find. It turns out that they do this every 50,000 years. In the first two games, the Reapers are terrific villains: frightening and implacable, a force of nature that will simply overwhelm everything and everyone in their path.

Take the Reapers in the Mass Effect video game franchise. For those unfamiliar with the story in this fantastic game series, you play as Commander Shepard, a human military officer who finds him- or herself in the midst of a crisis of galactic proportions. A race of sentient machines as large as starships called the Reapers will soon return to the galaxy and destroy every advanced civilization they can find. It turns out that they do this every 50,000 years. In the first two games, the Reapers are terrific villains: frightening and implacable, a force of nature that will simply overwhelm everything and everyone in their path.

And then it all goes off the rails in the third and final game.

Throughout most of Mass Effect 3, the Reapers are once again the overwhelming force. But then, in the end, the developers decided to reveal the “why” of what the Reapers are doing. And I have to admit, while I was curious about the “why,” the moment I learned it, the Reapers lost a great deal of their menace. Part of the reason for that is because the explanation made very little sense (something the game developers have been trying to fix with the release of downloadable content), but for some reason, the resolution of that mystery made the Reapers seem weaker.

And we don’t just see this de-threatening (that’s a word, right?) with the Reapers. Think of Darth Vader. In the original trilogy, Darth Vader is a monster in his black armor. Even his redemption at the end of Return of the Jedi didn’t weaken him. But when we were shown Ani the slave boy, suddenly Vader didn’t seem quite as menacing. The phrase, “Now this is pod racing!” did more to hurt Vader than any lightsaber ever could. The same thing happened to Boba Fett. Yes, it’s awful that he’s an orphan and yes, I felt bad when Mace Windu lopped off Jango’s head, but seeing that made me think less of Boba Fett because it made him seem weaker.

And we don’t just see this de-threatening (that’s a word, right?) with the Reapers. Think of Darth Vader. In the original trilogy, Darth Vader is a monster in his black armor. Even his redemption at the end of Return of the Jedi didn’t weaken him. But when we were shown Ani the slave boy, suddenly Vader didn’t seem quite as menacing. The phrase, “Now this is pod racing!” did more to hurt Vader than any lightsaber ever could. The same thing happened to Boba Fett. Yes, it’s awful that he’s an orphan and yes, I felt bad when Mace Windu lopped off Jango’s head, but seeing that made me think less of Boba Fett because it made him seem weaker.

And how about Sauron? I’m sure that J.R.R. Tolkien included some backstory that would go a long way to explaining why Sauron forged the ring and what motivated him to want to dominate Middle Earth, but quite frankly, I’m not sure that would help make Sauron seem like a better villain. Let him be a gigantic, disembodied fiery eye and don’t put him on the couch for psychoanalysis. He works better that way.

And how about Sauron? I’m sure that J.R.R. Tolkien included some backstory that would go a long way to explaining why Sauron forged the ring and what motivated him to want to dominate Middle Earth, but quite frankly, I’m not sure that would help make Sauron seem like a better villain. Let him be a gigantic, disembodied fiery eye and don’t put him on the couch for psychoanalysis. He works better that way.

So I seem to be caught in a conundrum. On the one hand, some villains are more effective and menacing if we understand their motivation and what drives them. But other villains work better if they remain mysterious and the reasons for what they do remain unknown. It almost seems, at least to me, that the key to all of this is whether or not the villain is “larger than life.” If they are, then they can be evil for evil’s sake without explanation. But if they’re more “down to earth,” then we need to know what drives them and what made them the way they are.

What do you think? Am I over-thinking this? What do you think makes a villain effective in a story?

Glad you’re back! I’d been missing your posts.

I think you’re spot on with your analysis of villains. We do need some bad guys with a back story, who are really just flawed humans (or flawed mutants, I guess 😉 ), but I hate it when the evil villains aren’t really evil — they’re “just misunderstood”. Real evil exists, and we have to acknowledge it in story.

I can enjoy both kinds of villains in a story, if it’s well done. Either version, when handled poorly, can become cartoonish. I think that the White Witch from Narnia is a good example of a villain that is truly evil, while not seeming over the top.

Great article, John.

I’ve really been bothered by this idea that villains have to be fleshed out by showing their “good side.” As I see it, evil doesn’t have a good side. And I’m not less inclined to believe a story if I saw the Orcs as poor, abused mutants that experienced unspeakable prejudice, forcing them away from the rest of society. Sorry, that approach would not make the Orcs more fearsome. The idea that they were forged to do more damage, to be more heartless, now that infuses fear in my heart.

I think your conclusion is right on–down-to-earth characters can be a mixed bag. They are most like humans and therefore need to be shown with our created-in-God’s-image/fallen-sin-nature conundrum.

Interestingly, the most fearsome villain in recent fantasy fiction, Lord Voldemort, has some background that could lead readers to be sympathetic toward him, but he himself makes that impossible. He was given the opportunity to be different and he spurred it. His choice is what makes him so fearsome. In turn, he becomes larger than life.

Becky

Well, two examples spring to my mind when you say this, both from television: Madame Kovarian and Regina Mills.

Madame Kovarian (Spoilers for Doctor Who season six) kidnaps Amy and manipulates her child to have Time Lord-like powers. After she’s left the base, she leaves a message for the Doctor:

Madame Kovarian: The child then, what do you think?

The Doctor: What is she?

Madame Kovarian: Hope. Hope in this endless, bitter war.

The Doctor: What war? Against who?

Madame Kovarian: Against you, Doctor.

So, we know she sees the Doctor as her enemy, but we really don’t have an idea why. At the end of the episode, River elaborates a bit, but it’s not a one-to-one explanation:

You make them so afraid(…) The man who can turn an army around at the mention of his name(…) But if you carry on the way you are, what might that word come to mean? To the people of the Gamma Forests, the word Doctor means “Mighty Warrior.” How far you’ve come. And now they’ve taken a child, the child of your best friends, and they’re going to turn her into a weapon just to bring you down. And all this, my love, in fear of you.”

As viewers, we get a global explanation, but not an analytic one. It could be summarized as “some people look at what the Doctor has done and see him as a monster.” Another exchange in the episode runs as such:

The Doctor: Even if you could get your hands on a brand new Time Lord, what for?

Madame Vastra: A weapon?

The Doctor: Why would a Time Lord be a weapon?

Madame Vastra: Well. They’ve seen you.

Regina Mills,(slight spoilers) on the other hand, is one of the main antagonists in ABC’s Once Upon a Time. We learn early on that she was originally an evil queen in a fairy-tale land who banished all the characters to our world and erased their memories, trapping them as ordinary people. We get oodles of backstory on her as the season progresses, including standardized “Mommy Issues” and “Tragic Love,” in an attempt to make her a sympathic character.

I think it worked too well. After the winter finale last Sunday, most of the fans were up in arms–not about Hook’s rape threats, but about the fact that Regina was not invited to a family dinner with Snow White, Prince Charming, Emma, and Henry. (Henry is Emma’s son and Snow White/Charming’s grandson, but also Regina’s adopted son). They ignored that Regina’s attempted to murder all of the above, erased memories, etc…just because she saved lives from a trap she’d set in the first place.

Let’s see, any other examples that come to mind? Not at the moment.

I think that the fleshing out of villains, giving them a backstory that might make us sympathetic toward them, is part of a worldview. It’s part of the worldview that says we are all born as blank slates. If good things happen to us, we turn out good, but if bad things happen to us, we turn out bad, and it’s the fault of the things that happened to us, not our own.

Which is, of course, false. But popular story makers have bought it, and portray it.

Another example of a villain that had a chance to turn around and did not is Loki from the Avengers movie.

I agree with Esther and other commenters – when writers bend over backwards to give villains a sympathetic story to explain their evil, it’s “part of the worldview that says we are all born as blank slates”. As Christians I don’t believe we should proliferate that kind of thinking in our stories. But while I believe we are all born as sinners with evil IN us, I also believe backstory can make a villain stronger. I don’t think we should sympathize with villains (ugh), but understanding WHY they do what they do makes them a little deeper. I liked the examples of Magneto and the White Witch (suggested by Lauren, above), and Voldemort (suggested by Rebecca). They have good depth without asking readers to be sympathetic.

The villains in my main book have always been a kind of mindless horde – think orcs, but sci-fi lizardy creatures. They didn’t have any depth until recently, when I fleshed out motivations for the reason WHY they’re trying to take over two new planets. Before, they were bloodthirsty for no good reason. But now I have shown that they consider their world over-populated, and are looking for new territory to spread out. Even a simple change like that can help make villains more understandable.

All very good points!

One trend I’m seeing is the “everybody is basically good” angle. Do you remember Lilo and Stitch? Stitch is the “villain”. He’s a monster created to destroy civilizations, especially large cities. Except Lilo makes friends with him and brings out his good side. By the end of the movie, there are no villains. I’ve always been very divided in my mind about it. On one hand, it’s good writing to have people following opposing goals that wind up creating conflict against each other. On the other hand, in a Disney, I’d rather there were Black and White. Make the Witch evil and the princess good.

In Tangled, Mother Goetha (sp?) isn’t evil for the sake of being evil. She uses Rapunzel’s magic hair to keep herself young, and she’s immensely selfish. That conflicts nicely with Rapunzel’s desperate desire to leave the tower and see the floating lanterns. Except by the end, we’ve seen Goetha manipulate, lie, cheat, and basically reveal her true nasty nature. I think she rates right up there with Malificent. Except Goetha is like someone you’d meet in real life.

I think it takes all sorts of villains to make a story, just as there is in real life. Some villains should do evil for evil’s sake, others should be convinced that they are really doing good, some should believe that the ends justify the means, and some should be so sympathetic that they border on being heroes. Real people are all of those.

Like others have said, it annoys me when the villain is portrayed as simply ‘misunderstood’, as if society is to blame for their evil ways. Everyone has a choice, and their crummy childhood or whatever doesn’t excuse their actions.

On the other hand, it really bothers me when a villain, especially a human one, is portrayed as wholly and completely evil. There is no person who is completely without good or beyond redemption. Sometimes, it seems like a writer justifies any action a hero takes against a villain simply by saying, “He’s evil. He deserves it.”

I think some of the most interesting villains mirror the heroes who oppose them. When the villain and hero come from similar backgrounds or were faced with similar choices, but chose to live their lives in completely different ways, the contrast shows the villain to be all the more terrible. The example that comes to mind is from the TV show Merlin. Morgana, the evil witch, justifies her actions by claiming to be misunderstood and oppressed. She thinks no one else could possibly know how she felt when she discovered she had magic, in a kingdom where that is forbidden. However, Merlin has been living with magic in the same household for a long time, quietly using his powers to do good. Whenever she hints that she had no choice, or that her behavior is justified, one look at Merlin’s actions under similar circumstances will prove her to be wrong.

Great thoughts John.

I wonder if the difference is “epicness.” Star Wars and LOTR are epics that need a big scary bad guy to anchor the conflict. The small, ragtag band of rebel Hobbits going against the mighty Empire and its one Ring of the Force, or whatever.

The other stories need the villain to be relatable. Magneto makes a much better bad guy now because we see his motivation, even if it goes too far. X-men can be out there, but it isn’t as epic and is built more in the real world.

My thoughts, such as they are on this crazy day.

I like the understandable evil more, because it gives the possibility of repentance. If used well, it can add so much to a story. One of the better examples I’ve seen is in the little-known anime Spiral: The Bonds of Reason. The villains are the Blade Children, who kill to defend their secret, and who torment the protagonist Ayumu as he seeks to both unravel their mystery and find his lost brother.

It’s a really good series in one sense because all the action is cerebral. The Blade Children use deathtraps rather than violence except as a last resort. But you soon find out that they are not only villains, but prisoners in their own evil, and their only hope is if Ayumu can become greater than his brother and save them from themselves. Even the worst of them is motivated not by pure evil but by despair. If they were just mysterious and faceless, something would be missing.

I think faceless only works when the point of the book is to show how cool the heroes are, and the villains are just a means to an end to that. Even then its kind of eh, as it’s just different levels of cannon fodder who increase in power and evil deeds.

It all depends on the conflict you want the heroes to have. Using the examples that have been brought up, since I’m too lazy to come up with my own…

Star Wars? Luke would have less conflict about Vader being his father if he could see a sympathetic side to this Dark Lord of the Sith; since he can’t, his conflict about trying to redeem this man increases.

X-Men, with Magneto as its many-faceted villain, often drifts into social commentary: if ends justify the means, when killing becomes right, etc. Thus, having a villain who provides sympathetic justifications for his actions heightens the conflict; if he were strictly evil and not at all sympathetic, there would be less conflict.

The Lord of the Rings’ focus is on persevering when the darkness seems unstoppable. Thus, having a seemingly unstoppable, completely evil, overwhelmingly dark power for its villain heightens the conflict. If the slightest hint that Sauron might waver, might be a sympathetic character, appeared, the conflict would diminish. Saruman and Denethor, as non-central villains, can be more fleshed out and – however slightly – relatable, because that can only add another layer of conflict by showing how Sauron twists and corrupts those who should be opposing him from good to evil – in a way, increasing their awareness of Sauron’s darkness and power, and thus expanding the conflict.

(Yes, occasionally villains can pull off both roles; the Joker pushes Batman to the limits of what Batman can do while still claiming to be good, yet we have no sympathy or understanding of the Joker’s depraved lack of motive. But those are rare, in my opinion)

So, in short, I agree with Jason when he said above that it depends on the feel of the story. What do the heroes need? Conflict about what lengths they can justly go to in seeking to stop an evil, before they become just as evil themselves? Or simply a purely dark power which they must persevere in opposing?

On a more Bible-y note:

Villains such as Sauron, Emperor Palpatine, Boba Fett, and the Reapers are great, because they remind us of Satan, the prince of this world who opposes the Almighty and is – to our knowledge – completely and entirely dark and evil, with no trace of sympathy.

Villains who are more complex, more understandable, more sympathetic (Magneto, Lilo, and possibly even Voldermort would fall in this category), are great because they remind us of ourselves: that as fallen mankind, individuals have incredible potential for evil; I would contend that they don’t so much demand sympathy from us, but that they demand we recognize how only a slender thread of grace separates us from them.They remind us that “there, but for the grace of God, go I”; and, simultaneously, that as far as dealing with our fellow fallen mankind is concerned, the possibility of redemption is always there; after all, God redeemed us. (Also, the complex villains really do provide more opportunity for questions of moral quandries, social commentary, and where the line between good and evil falls on a concrete level.)

Lastly, random ‘freebie’: It seems to me that every time a villain – Voldermort, Loki, Magneto – has the chance to turn from evil and rejects that opportunity, choosing to persist in wickedness, they disprove the worldview that blames all misery and vileness on upbringing and traumatic experiences. They had every opportunity to become more… and spat on those opportunities as they turned away.

This is my first time posting here, so I’ll try not to say anything repetitive. I think it depends on your ultimate goal for the character or characters is. If you’re going to give the villain a possibility of redemption or if you just don’t want them to be pure evil, backstory is helpful. Sometimes they’re evil enough that I really don’t care what their backstory is. Once or twice, I’ve seen authors flesh out their villains enough that they don’t sound like cardboard cutouts, but they aren’t the least bit sympathetic either. One example is The Judgment Stone, by Robert Liparulo.

Mild Spoilers:

Each member of the Clan has a fairly distinct personality that we see a little bit of, but they’re not sympathetic. At all. If you’ve read the book, you know what I’m talking about.