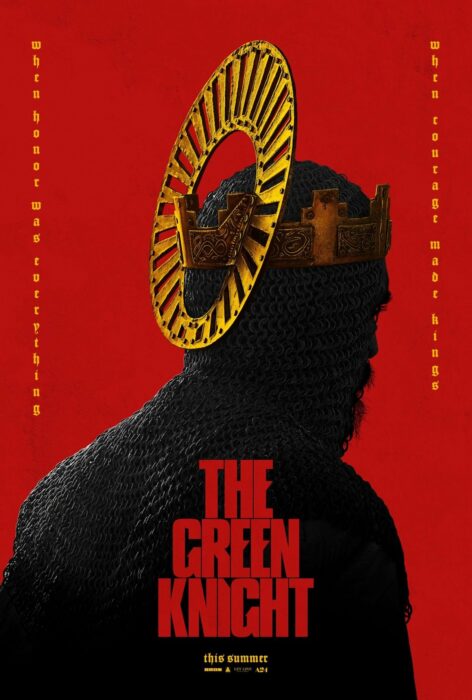

‘The Green Knight’ Film May Not Outmatch the Original Poem’s Challenge of Human Virtue

Because I teach about the medieval romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, students and friends often assume I’m excited about director David Lowery’s upcoming film The Green Knight.

I’m not.

According to the current Rotten Tomatoes summary, the film supposedly “honors and deconstructs its source material in equal measure.” But I tire of deconstructing old narratives. Must everything be dismantled by modern hands? Have we nothing to learn from people who came before us?

Furthermore, I’m sure the profoundly Catholic-Christian ethic of Gawain’s anonymous author1 will at best be misunderstood.2 Meanwhile, even given the trailers’ aesthetic interest, and ignoring my adaptation concerns, my husband and I won’t see this film because we won’t pay for the objectification of its actors: The Green Knight is rated R for, among other causes, “graphic nudity.”

However, as someone who has intensely loved, studied, taught, and related to Sir Gawain and the Green Knight for the past fifteen years, I’m overjoyed to give a teeny primer on the plot, which offers profound and unsettling insight into human virtue.

I’ll chop your head if you’ll chop mine

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (from original manuscript, artist unknown)

On New Year’s Day in young King Arthur’s court, Arthur’s nephew Gawain, renowned as the most courteous of knights, sits in his seat of honor during the festivities. However, a huge and bearded, all-green man crashes the party. He challenges the court to a “game”: Today, one of you must try to cut off my head, and in a year I will return the stroke in the Green Chapel.

The court falls silent. The Green Knight jeers at their supposed valiance. Then Gawain perceives Arthur’s shame, and volunteers to play the game. He swipes off the Green Knight’s head—but the Green Knight promptly picks up his own head and taunts, “See you next year!”

As the set time approaches, Gawain dutifully sets out to find the Green Chapel and receive his own returned decapitating blow. He finds a green castle, ruled by a large-bearded man who informs him that the Green Chapel is not far. This dude also invites Gawain to play an odd game. (Suspicious much?)

This new game is also an exchange. For three days, the lord will go hunting and give Gawain whatever he catches each day. Meanwhile, Gawain will party at the court each day and give the lord whatever he receives there.

The hitch is that the lord’s young wife apparently has the hots for Gawain, which leads to some very awkward seduction attempts. These scenes would have been wildly funny to the original audience, because Gawain, famed for his courteous reputation, can’t just unceremoniously tell her off—that would be rude to the hostess. But of course he can’t actually let himself be seduced!

Stuck between a rock and a hard place, Gawain and his audience squirm. Each time he squeezes by with only kisses, and so he must bestow these same kisses upon the lord during their daily exchanges.

The real test and the real failure

But on the third day, the seductress offers him something other than carnal pleasure: a green girdle (belt) guaranteed to protect him from deadly wounds. That Gawain does accept. And that he does not give the castle’s lord in the exchange.

The next day, New Year’s Day, Gawain sets out for the Green Chapel. This day is important to the Catholic Church because it’s traditionally the day of Christ’s circumcision, when the infant Jesus received a cut in the flesh to show his mortality. When Gawain gets to the Green Chapel (wearing the belt beneath his clothes), he’s surprised. It’s not a chapel at all, but a “devilish” pagan burial mound, with grass growing atop it.

Inside, the Green Knight toys with him. Twice Gawain offers his neck, and twice the Green Knight swings but does not connect. Finally, on the third swing, the Green Knight hits Gawain with the axe:

He hammered down hard, yet harmed him no whit

Save a scratch on one side, that severed the skin(lines 2311–2312)

Then the Green Knight reveals that he is actually the lord of the green castle. It was he who put up his wife to tempt Gawain, but her caresses were not the true test: the true test was whether Gawain would exchange the belt. He says,

“True men pay what they owe;

No danger then in sight.

You failed at the third throw,

So take my tap, sir knight.”(lines 2354–2357)

The knight errant (and erring)

Gawain has tried to make right choices. He bravely volunteered to preserve his king’s reputation. He honorably set out to keep his part of the decapitation game. He barely wriggled between being “rude” to his hostess and being immoral. But in the end he failed, because of the magic belt.

It’s an understandable failing. The Green Knight says it himself:

“The cause was not cunning,

nor courtship either,

But that you loved your own life;

the less, then, to blame.”(lines 2367–2368)

But instead of melting in relief, Gawain is furious:

So gripped with grim rage that his great heart shook.

All the blood of his body burned in his face

As he shrank back in shame. . . .“Now am I faulty and false, that fearful was ever

Of disloyalty and lies, bad luck to them both!”(lines 2370–2384)

Gawain has received a cut in his flesh to show his mortality: though his knightly exploits make him a living legend, he’s only human. Gawain comes face-to-face with his fallibility—and he doesn’t like it. He’s spent an agonizing year contemplating his mortality, but he’s never fully accepted that human frailty is also a moral good.

It’s the perfectionist’s response. It’s the rule-follower’s story. It’s the legalist’s Arthurian legend!

Startlingly, the Green Knight laughs:

“Such harm as I have had, I hold it quite healed. . . .

“I hold you polished as a pearl, as pure and as bright

As you had lived free of fault since first you were born.

And I give you, sir, this girdle.”(lines 2391–2395)

So the Green Chapel is a chapel after all: there, Gawain receives absolution. And the fact that it’s a tomb, which so scandalized Gawain at the outset, has clear Christian implications. He enters the tomb to die, but he receives life—along with keenly felt knowledge of his limitations—instead.

The Green Knight and new life

The poem’s ending is ambivalent. Gawain still seems ashamed. King Arthur’s court turns the green girdle into a fashion trend, seemingly missing the significance of the Green Knight’s message. Yet in a poem in which things are rarely what they seem, Gawain has encountered the scandalous Gospel, and it has left him rattled.

Many of us haven’t read Sir Gawain and the Green Knight since college and may be intrigued by those gorgeous trailers. Many readers may remember so little of Gawain that the film’s interpretation becomes the only version they know.

As one glowing film review states, the film’s message is “that the only true value of a thing in this world is that which we find in it for ourselves.”3 If this interpretation of the film is accurate, this is nearly opposite of the original Gawain, in which we come, appallingly and offensively, face-to-face with the delusions behind our own sense of value. We see that all our human virtue systems, whether modern progressivism or King Arthur’s famous honor code, cannot make us perfect. We are not sufficient. But rather than give up in despair, we must go to a scandalous chapel—a tomb—to own our fallibility and receive new life, a life we are given freely with joyous laughter.

No matter the beauties of David Lowery’s film The Green Knight, it can’t outmatch the thrilling or beautiful truth of the original Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

- The author is often called the Pearl poet, after another of his works. ↩

- I also have smaller quibbles, like the fact that the filmmakers made Arthur and Guinevere “fading, sickly monarchs in order to imply some rot in the heart of Camelot,” rather than following the poem’s lead. Gawain pits the youthful assurance and optimism of Arthur’s court against the older Green Knight, who laughs at the “beardless children” (line 280). ↩

- “‘The Green Knight’ Review: Dev Patel Decapitates His Destiny in David Lowery’s Arthurian Masterpiece,” David Ehrlich at IndieWire.com, July 26, 2021. ↩

As someone who has been reading different versions of this for a wider King Arthur retelling, I really appreciate this! Thank you for lending your insight to this!

Thank you, Emily! I love the poem with all my heart. What versions have you been enjoying?

I love this story! I think it’s my favorite medieval lit. story. It’s interesting that this came out right before the movie! 🙂

https://www.amazon.com/Gawain-Green-Knight-Pearl-Orfeo/dp/0358652979/ref=sr_1_3?dchild=1&keywords=sir+gawain+tolkien&qid=1627607330&sr=8-3

Oooo, with Sir Orfeo, too! I love all of those poems. I do hope that the film creates more interest in the original tale. From what I’ve read of the film, they are almost two entirely different stories!

Yep, the World is quite against Christ… who knew? 😉

Its sad, but inevitable. Time to create our own works!

It’s a bit of a bummer that most Christian productions veer away from more gritty tales fraught with crude situations. Those are the more telling of the human condition.

“Must everything be dismantled by modern hands? Have we nothing to learn from people who came before us?” Excellent questions, and as one who pursued graduate studies in literary theory, I too grew weary of this approach to virtually all pre-20th C literature. I taught Gawain “straight” to a group of homeschooled high school kids, and they loved it! Medieval literature can still speak to us meaningfully in our post-modern world.

Robin, YES!!! I am also a high school English teacher with an MA in Literature, and this was my exact question and concern. Have you read anything by C. S. Lewis on the concept of “chronological snobbery?” I bet you would love it as much as I do.

Watched the movie. Still have the original on my “to-read” list. You didn’t miss much. It’s very much an arthouse filck (though ironically it’s none of the actors who are nude in the film, but some random giants).

Ranted a bit about it here: https://natewinchester.wordpress.com/2021/08/09/i-need-a-term-for-this/ (along with ranting about other trends)

Not even sure it could be called a deconstruction because I’m not sure the writer understood the source well enough to get that far. It’s more like a deconstruction of a bad parody of the source.