To Shape a Story is to Shape a Soul

I’m a naturally argumentative gal and can go to absurd lengths to make a point. Once I wrote a paper about Eugene O’Neill’s play, Desire Under the Elms, without mentioning Sigmund Freud or the Oedipus Complex. The professor was visibly annoyed to give me an A because the entire play is about the Oedipus complex. He still remembers me as “the psychology major who refused to write about Freud.”

Absurd lengths, folks.

The passionate pursuit of the perfect argument integrating ethos, logos, and pathos led to an early love of apologetics. From the first chapter of Don’t Check Your Brains at the Door by Josh McDowell and Bob Hostetler, middle-school me was hooked. Apologetics blended my interests in theology, history, and philosophy.

And it gave me an excuse to argue with people.

When I first lost an argument

But something changed when my husband left church ministry. I trace it back to that point because it was the first time I lost an argument and felt it. Until the day my husband was asked to resign, none of my debates had material consequences. I offended a friend or two, but never enough to break fellowship. I made mistakes and felt foolish sometimes, but the fallout was minimal. This time, his resignation meant that I had surely failed to convince people that he was a good pastor. My losing the argument resulted in us being jobless and essentially homeless with a newborn and toddler.

Obviously, none of that is true. I wasn’t responsible for those painful circumstances or the ultimate outcome. Churches are filled with broken people, and all pastors have wounds. But it still felt true, and my drive toward apologetics intensified.

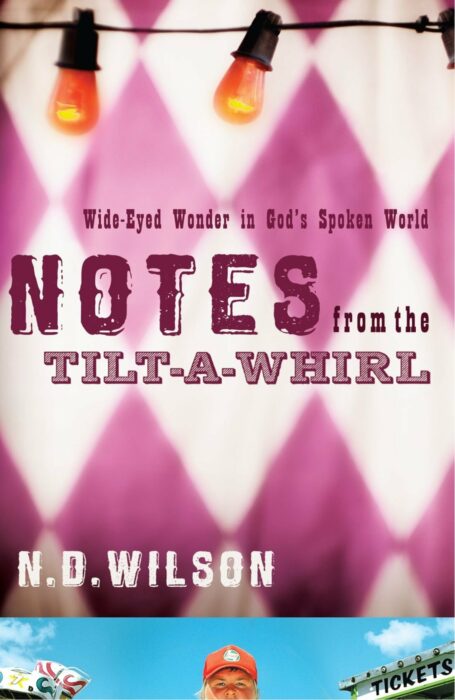

During that same year, I read a book called Notes from the Tilt-A-Whirl. The book brought me much comfort and reassurance, and I became curious about the author, N. D. Wilson. In an interview in World magazine, I discovered a quote that I have kept pinned to my desk ever since:

During that same year, I read a book called Notes from the Tilt-A-Whirl. The book brought me much comfort and reassurance, and I became curious about the author, N. D. Wilson. In an interview in World magazine, I discovered a quote that I have kept pinned to my desk ever since:

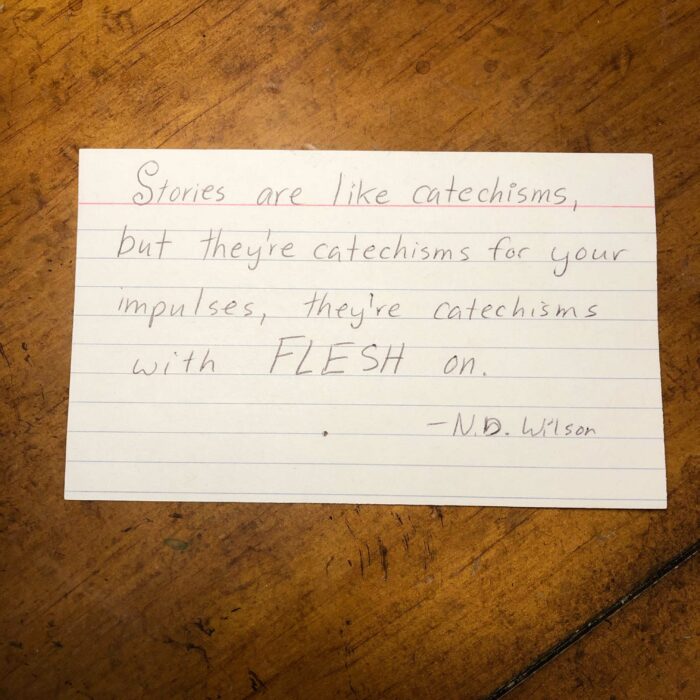

“Stories are like catechisms, but they’re catechisms for your impulses. They’re catechisms with flesh on.”1

That’s when I realized that story is the sneakiest form of apologetics.

We are made of stories, not just truth claims

From both a psychological and theological standpoint, we are made of stories. God spoke the world into being, and He gave us, His image-bearers, the same ability to create with words. We process the world through stories, we explain ourselves to others through stories, and as we read, listen, and watch media, we integrate the narratives into our own. This is part of why reading Scripture daily can change our character. It’s also why deconstruction stories can be compelling but damaging.

We are the stories we tell ourselves, especially during our formative years. All the weeks in lockdown last year gave me time to consider just how much story has shaped my moral imagination.

The moral-shaping power of imagination

I honestly don’t remember when I first read C. S. Lewis’s myth retelling, Till We Have Faces, but I felt a deep connection to the main character and her struggle to find her purpose and worth. Her anger at the unfairness of the gods and her lack of insight into her jealousy of her sister cut me to the quick. Her Job-like brokenness near the end of the book still resonates with me: “The complaint was the answer. To have heard myself making it was to be answered.”2

When I finished The Lord of the Rings in high school, I realized I’d absorbed a deep love of forests and green places and admiration for loyalty and courage. I was determined to never let my warrior heart wither behind a cage. When I discovered Michael Crichton in college, I developed a deep suspicion of scientific advancements, especially human subject experiments as illustrated in The Terminal Man. Crichton wasn’t a Christian, but he believed science needed ethical limits. I’m still drawn to tech-gone-awry stories (and have written a few myself) because they illustrate the need for a Judeo-Christian ethic in the sciences.

And now as a mom, I see how read-alouds and favorite movies shape my children and teach truth (or lies) almost subconsciously. C. S. Lewis recognized this sneaky power of story when he discussed his Narnia series:

On that side (as Author) I wrote fairy tales because the Fairy Tale seemed the ideal Form for the stuff I had to say. Then of course the Man in me began to have his turn. I thought I saw how stories of this kind could steal past a certain inhibition which had paralysed much of my own religion in childhood.3

We are made of stories, and those stories come from somewhere. They shape how we see the world, where we travel in it, and what we love. They reflect good or evil, truth or lies, beauty or ugliness. That’s why Christian fiction matters so much. It allows us to win the argument without arguing.

To shape a story is to shape a soul.

So tell me: what story are you telling yourself and where did it come from? Can you see ways it is shaping your soul?

- From “Catechisms with Flesh On”, interview of N. D. Wilson by Marvin Olasky in WORLD magazine, February 27, 2012. Wilson “fleshes out” more ideas like this in Notes from the Tilt-A-Whirl and Death by Living, if you’re looking for books to add to your Goodreads. ↩

- Till We Have Faces was C. S. Lewis’s only myth retelling. He and J. R. R. Tolkien both considered it to be his best fiction work, and I heartily agree. ↩

- From “Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s to be Said,” C.S. Lewis, The New York Times, Nov. 18, 1956. Accessed online at A Pilgrim in Narnia blog. ↩

This is such a great article. I agree with the author’s takes wholeheartedly. And I’m glad someone else recognizes the absolute brilliance that is Notes from the Tilt-a-Whirl, by N.D. Wilson. Honestly believe more people should read this book over how-to-argue-for-your-faith stuff, and it’s a great read even for nonbelievers who are interested in the big moral/spiritual themes of the world.

Thanks, Daniel! I absolutely agree that Notes from the Tilt-A-Whirl is better than many apologetics books. Death by Living is similar. I think they should be considered extended prose poems with theological and philosophical themes. Wilson has such a lyrical writing style in both! I hope to develop some of the ideas in this article a little further, specifically regarding psychology and personal narratives, but we’ll see how the research goes in that direction.