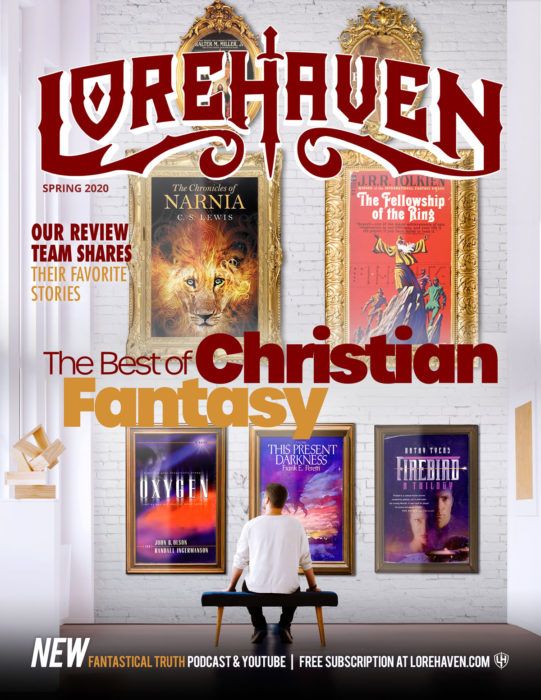

The Best of Christian Fantasy

In all other issues of Lorehaven, we review the latest Christian-made fantastical novels. This time we asked our review team to choose and review their favorite Christian-made fantastical novels from any era.

Future Lorehaven issues might include even more novels that count as our favorites. For now, however, we commend to you these ten tales.

- A Canticle for Leibowitz, Walter M. Miller Jr.

- Flora & Ulysses, Kate DiCamillo

- The Lord of the Rings, J. R. R. Tolkien

- The Firebird series, Kathy Tyers

- Rescue, F. E. Greene

- Oxygen, John B. Olson and Randall Ingermanson

- The Chronicles of Narnia, C. S. Lewis

- This Present Darkness, Frank E. Peretti

- The Visitation, Frank E. Peretti

- Phantastes, George MacDonald

A Canticle for Leibowitz

A Canticle for Leibowitz

reviewed by Shannon McDermott

Since the invention of the atomic bomb, people have debated whether humanity is stupid enough to unleash the nuclear apocalypse. This, however, brings another question: Is humanity stupid enough to unleash the nuclear apocalypse twice?

In A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959), Walter M. Miller Jr. paints the cycle of fall and rise and fall. The story spans over a thousand years, flying from the Middle Ages to the struggling rise of science to the precarious apex of civilization.

Canticle was released fifteen years after the 1945 American bombings of Hiroshima and Nagaski and therefore reflects Cold War fears. At the same time, the story is painfully modern as it examines our dissatisfaction with prosperity and technological miracle, and debates mercy and the evil of pain.

Miller’s overall tone is somber but leavened with humor. Although the story is not “Christian” in an explicit sense—readers meet faithful characters, but no converts—it handles its Christian monastic order with profound understanding and ultimate sympathy. Miller’s writing is masterly and deeply human.

A Canticle for Leibowitz is a masterpiece that mixes profundity, heart, and superb craftsmanship.

Best for: Fans of dystopian and science fiction.

Discern: Multiple characters die violent deaths, a few somewhat graphically; a mother and baby suffer from nuclear fallout; allusions to torture and cannibalism; wars, including nuclear attacks, are referenced but not seen in any detail.

Flora & Ulysses

reviewed by Phyllis Wheeler

What’s a ten-year-old girl named Flora to do when her mother dotes on a pretty porcelain lamp named Mary Ann instead of on Flora? Become a cynic, of course!

Kate DiCamillo’s Flora & Ulysses (2013) tells a winsome and magical story about a tomboy girl and a squirrel. Despite her self-declared cynicism, Flora adores comic books, especially those about an unassuming janitor who transforms into a shining light of rescue. So she is delighted when a squirrel in the neighbor’s yard apparently gains superpowers, and becomes able to fly and lift heavy things.

Meanwhile, the squirrel is suddenly able to understand what this human girl is saying. He even types poetry on her mother’s typewriter. But her mother declares him diseased and wants to put him out of his misery. Is Flora’s life starting to resemble a comic book? What’s next?

Flora & Ulysses indirectly echoes the author’s Christian worldview by evoking a vision of healing and spiritual wholeness.

Best for: Older kids (for example, from ages eight to twelve); anyone who enjoys uplifting stories with some fantastical quirks.

Discern: Instances of lighthearted, anything-can-happen magic; depictions of an argumentative, unhappy marriage.

The Lord of the Rings

reviewed by Elizabeth Kaiser

Good things can be twisted for evil. But what about an object that has been evil from its very inception? Can such a thing be turned to good?

J. R. R. Tolkien’s genre-defining novel The Lord of the Rings is a “trilogy of one,” in that the story flows from book to book without any interruption. This bestrides an epic fantasy world as deep as it is wide, melting down the myths of northern Europe to forge a newly relevant synthesis—fresh as spring rain, rooted as the mountains.

The Lord of the Rings was sparked by the success of Tolkien’s first novel, The Hobbit, and stars Frodo, nephew to that book’s hero Bilbo Baggins. However, this sprawling “sequel” set in the fantasy world of Middle-earth at first appears prosaic. When the eccentric Bilbo decides to retire from respectable country life, he bequeaths his nephew Frodo his home and all it contains—including a curious magical ring that may or may not encircle the fate of the world. From there, events spiral outward into realms of high poetry, encompassing a supporting cast so well-realized and so instantly classic that readers to this day argue over who is the hero of this story.

Tolkien’s childhood in South Africa, his service on the western front during World War I, and his exposure to diverse cultures and landscapes throughout his life are reflected brilliantly in his varied depictions of dramatic—yet grippingly believable—terrains and folk. He paints a lyrical setting so realistic that many readers feel Middle-earth seems more alive than today’s world, a spiritual landscape from which any reader can draw countless morality tales.

The story’s first installment, The Fellowship of the Ring, brings a diverse brotherhood together and starts them on a journey fraught with perils within and without. The tension between individuals—their perspectives and what each person thinks is the best choice to make—illuminates a truth of group dynamics in any era: teamwork is always tricky to maintain.

From there, The Two Towers sees the band flung in different directions. Yet the story details how, despite each hero’s sense of failure, each journey actually works its own important thread through the tapestry of the grand design. Readers can draw encouragement for their own lives: such a truth must also be true in us, so long as our hearts do not waver from seeking the light.

Finally, The Return of the King has reduced many a reader to tears of joy. Echoes of the Christian’s hope radiate throughout this climactic volume. Old friends find their paths at last converging after dark journeys, and seemingly impossible hope blazes forth in a new dawn which will last for an age.

By the grand finale, The Lord of the Rings portrays what Tolkien himself called eucatastrophe, that is, the “good catastrophe,” in which certain despair suddenly turns into joyous victory. Such moving resolution helps Christian readers expect that Christ’s victory at the end of this age will be even more fulfilling, and until then, we should take heart and press forward, to greet our true King’s triumphant return.

Best for: Teens and adults seeking a masterwork of high fantasy.

Discern: Strong violence and peril; depictions of magic, including sorcery, possession, and the use of objects imbued with power; some horror.

The Firebird series

reviewed by E. Stephen Burnett

Lady Firebird Angelo has grown up knowing she might someday die for her people. As the thirdborn daughter of the royal family of the planet Netaia, she has trained for combat as a “wastling,” destined for suicide. Unfortunately, during her first engagement in space, she fails. Firebird is captured alive by the enemy. This galactic Federacy employs Firebird’s new captor, Field General Brennen Caldwell,1 who is both intriguing and supernaturally telepathic.

Their encounter leads to the first of Lady Firebird’s drastic life changes in Firebird, book 1 of Kathy Tyers’s Firebird series. Tyers described Firebird’s original version, from Bantam Books, as a “cultural conversion story.” Yet since then, newer versions from Christian publishers enhanced Brennen’s commitment to an Eternal Speaker. That unseen entity has promised a divine messiah who hasn’t yet arrived.

Book 2, Fusion Fire, and book 3, Crown of Fire, follow Firebird’s journey in the stars, confronting the wars between them and the evils of her narcissistic sister, Phoena.

Meanwhile, Firebird gets to know her new people, including the telepathic Sentinels who gained their abilities from forbidden science. She also discovers supernatural gifts of her own, with great power to wield for good, or else to bring destruction.

All throughout, Tyers deftly describes other worlds, adding color to landscapes and intensity to emotions, especially in those my-mind-to-your-mind entanglements. Firebird’s musical talent adds even more atmosphere, not often seen in fiction, much less space opera. This trilogy—continued years later in books 4 and 5, Wind and Shadow and Daystar—marks a fantastic find for Christian fans and beyond.

Best for: Older teen and adult readers who love space opera with romantic flair.

Discern: Suicidal thoughts, intense and possibly sensual telepathic encounters, emotional abuse and manipulation, effects of torture, alternate-universe timeline in which Jesus Christ didn’t become incarnate until centuries after space travel began.

Rescue

reviewed by Audie Thacker

Bad days aren’t uncommon, but when things go bad for Pearl Sterling, they do so quickly and steeply. On one bad day, she loses her job, her home, and pretty much everything of any value to her. These losses leave Pearl with two terrible choices: match up with a boorish rich boy, or try to find a nearby castle that no one in town can see.

Rescue, the first book in F. E. Greene’s By Eyes Unseen fantasy series, is about two days in Pearl’s life: in the first, things go very wrong, and in the second she begins the process of leaving her old life behind to live among quirky and compassionate followers of a mysterious king. While Pearl herself largely remains the focus, several other fascinating and even atypical characters are introduced and developed along the way. This book kicks off a series, so it’s mostly concerned with world-building and introducing the players, but there’s quite enough here to hold a reader’s interest throughout this story and the ones that follow.

Best for: Young adults and older.

Discern: One character who essentially portrays Christ.

Oxygen

reviewed by E. Stephen Burnett

Once every two years, Mars veers closer to Earth, and at about the same rate the red planet orbits back into the news. Usually this happens when NASA launches another probe, or SpaceX founder Elon Musk insists his latest rocket-related antics really will someday send humans to colonize other worlds.

For Christian speculative fans, however, a minor Martian invasion occurred in 2001 with the publication of Oxygen. This sci-fi thriller from John B. Olson and Randall Ingermanson followed the first human mission to Mars, starting in the year 2012.

In this now-alternate history, there was no Curiosity probe, no Olympic Games or presidential election hogging the headlines, and no grand promises for amazing NASA missions followed only by budget cuts. Instead, readers join the Ares program, in progress, to send a four-member team of actual people to Mars.

Our heroine is Valkerie Jansen, a microbial ecologist whom we meet while she’s camping near an erupting volcano, as one does. To this day, Valkerie could be one of the most likeable and naturally strong female characters in Christian-made fiction. Not only is she one of the few female scientist heroines about the place, smart and ambitious, but she also stands up for her faith, defending her people while conceding Christians’ flaws. This includes her own vulnerabilities, such as her fears about being thrown so quickly into NASA’s program, where her values may contrast sharply with the politics and secrets of the other astronauts.

Still, this is no “message fiction.” Valerie and her story uphold general themes of biblical faith: God does exist, and he will take care of people. Institutional churches mainly cameo in the form of culturally separatist Christians in the background, who seem to oppose the Mars mission. (Back in actual history, when too many people of all religions ignore space programs, NASA might plead for this kind of controversy.)

Our real villain, however, is unknown. Either way, after a wind-tossed launch and in-flight repairs, Ares 10 has a problem: an explosion that endangers the ship. Who’s the saboteur? Everyone aboard feels like a real, sympathetic person, so readers may not want any of them to be the villain. This uncertainty fuels the suspense of Oxygen. Still, it is the Ares mission’s success or failure, the crew’s competence, and the fear of unknowns, that provide the crew’s opposition en route to Mars.

A 2002 sequel, The Fifth Man, follows the crew as they (spoiler alert) continue their mission on Mars itself. This time they seem to be plagued, not by a saboteur, but by a stowaway—a haunting presence that might kill the mission, or any of them.

In both episodes, Olson and Ingermanson write fast, fit, and smart. They know their science and characters, though they err on the side of emphasizing characters.

Despite Oxygen’s then-futuristic starting year, the books don’t feel like sci-fi. That’s by design, the authors conclude. For humans to reach Mars, “technology is not an issue. Most of what we need exists right now, and the rest is well within our grasp” (page 366). Still, plenty of factors prevent this journey. Christians wanting to explore harder science fiction, set in our own world, might empathize. In theory, we have all we need to explore more Christian-made sci-fi realms for God’s glory. Yet until our crafts get faster and better, Oxygen (and The Fifth Man) will help satisfy this yearning.

Best for: Adult fans of “softened” harder science fiction who also don’t mind a little romance.

Discern: Allusions to creation versus evolution and debates over microscopic alien life, as well as references to in-flight flirtation and chaste romantic moments.

The Chronicles of Narnia

reviewed by E. Stephen Burnett

By Aslan’s mane, one cannot collect any sort of list for the best Christian-made fantastical fiction without including C. S. Lewis’s septet, The Chronicles of Narnia.

From the Oxford scholar’s first Narnia journey, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950) to The Last Battle (1956), all the seven chronicles have delighted and engaged millions of readers, far beyond the “children’s” label often ascribed to the series.

What if you only read one or more of the books as a child? Or what if you have only read the first book, and only followed Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy through that magic wardrobe into that winter-locked land in need of Christmas and then Aslan’s spring? If so, then by the Lion, you as an adult shall be blessed. Read the Chronicles today, all of them, and in publication order (yes, Narnians, we will die on this hill).

As Lewis once wrote of his friend J. R. R. Tolkien’s epic fantasy magnum opus, so the same endorsement could apply to each Narnian episode: “Here are beauties which pierce like swords or burn like cold iron. Here is a book which will break your heart.”

Alas, those beauties often get blunted or made lukewarm by the persistent myth spread by well-meaning readers, including many Christians, that the Narnia books are merely “allegorical.” (For example, one author even wrote that Professor Kirke’s mansion “is symbolic of the church” while the wardrobe “symbolizes the Bible.”)

But the “allegory” label ignores the stories’ true purpose according to Lewis, who insisted on calling his world a supposal. In one letter, Lewis wrote that his Narnia stories answered the question, “What might Christ become like if there really were a world like Narnia and He chose to be incarnate and die and rise again in that world as He actually has done in ours?” Lewis then concluded, “This is not allegory at all.”

Case closed. And Aslan be praised that it is closed, because if we turn these stories into mere allegory, we might end up using Narnia like a mere code or container pointing to “higher” ideals. Like the foolish Uncle Andrew, we might stand in the middle of a wondrous world being created by a Lion’s song, and think only of the stuff we can shove into the soil to dig up more of the machine parts that we want. Narnia’s beauties, however, are far greater than this. By humbling ourselves as little children, we are better placed to gaze up into Aslan’s not-tame eyes and golden mane. Then, by knowing Aslan there for a little, we might know Jesus better here.

Best for: Readers of all ages who love adventure, whimsy, and profound truth.

Discern: Strong magic, often based in Aslan’s power but often operating as a “natural law” of Narnia and the lands beyond, including magic by evil creatures; violence, including actions such as beheadings that are described in few words; some swear terms and even misuses of God’s title, yet hidden by British spellings.

This Present Darkness

reviewed by Austin Gunderson

In the early 1980s, “Christian speculative fiction” wasn’t a thing. Sure, Pilgrim’s Progress and Ben-Hur were staples in Christian libraries, and J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis were giants. But fantastical fiction targeted specifically at a Christian audience hadn’t come into its own.

That all changed when struggling former pastor Frank E. Peretti’s This Present Darkness was published in 1986.

Peretti’s supernatural thriller begins in Ashton, a small college town on the northwestern plains. One wouldn’t consider this place as ground zero for a demonic conspiracy to dominate the globe. But the essential conceit of Peretti’s story is that human action affects the spiritual plane, and vice-versa.

Two men anchor the narrative’s physical dimension. Marshall Hogan is a big-time reporter who naïvely thought his new gig as editor of the Ashton Clarion would help him settle down and reconnect with his family. Hank Busche is a young pastor with a knee-jerk prayer instinct who can’t comprehend why his tiny congregation is so disrupted by his fidelity to God’s Word. When local officials start acting strangely, and things start going bump in the night, the two men find themselves drawn into a conflict for which neither is fully prepared. For evil is hard at work in Ashton—an evil that will threaten their relationships, their livelihoods, and ultimately their lives.

But that’s only half the story. The other half unfolds in a spiritual realm of persistent violence and high adventure. For mighty Tal, captain of the Host of Heaven, has arrived in Ashton to foil the schemes of Ba’al Rafar, demon prince of Babylon. Outnumbered and outmatched, Tal must use subterfuge to counter Rafar’s hordes. He must rely on human beings.

Peretti imagines what spiritual warfare might look like, to human eyes that can see like Elisha’s in 2 Kings 6. For this end, Darkness draws heavily upon the imagery of demonic principalities and martial messengers found in Daniel 10. Although at times cheesy—for example, the story uses “prayer cover” as the equivalent of air cover—Peretti’s pictures imbue the ordinary with cosmic significance.

Indeed, the novel’s realism and authoritativeness ended up influencing the prayer-warrior movement within the evangelical and charismatic church. For his part, however, Peretti himself never touted his depictions as prescriptive, and eventually shifted from angels-vs-demons stories to other flavors of paranormal fiction.

The prose is best described by that now-cliched adjective “cinematic.” Its lavishly rendered visual detail and dynamic action choreography charge it with a heightened sense of immediacy. But it’s also a slow-burn detective thriller that explodes into a rollicking melee of interspliced realities, leaving resonant questions echoing in the reader’s mind: How does one differentiate between the world, the flesh, and the devil? How powerful is prayer, really? And can God really accomplish his will through even the wickedest forces in the heavenly realms?

Although the villains’ strategies—neopaganism and the New Age movement—may seem dated today, these social and rhetorical tactics will feel all too familiar to culture-war veterans. Double standards of moral purity? Disingenuous calls for tolerance and inclusion? A numbing insistence that resistance is aggression? Whatever it takes to secure an advantage, that’s what the Enemy will employ.

In the face of such guile, heroes can’t always look respectable. It’s no accident the angels must sneak in under the radar while the demons get to descend from above. It’s also no mistake that enemies have turned Ashton’s most prestigious institutions into strongholds of darkness. This is a hostile, post-Christian environment in the heart of Americana. Here even the smallest acts of faith can demand great courage and elicit great reprisal. Let the savvy reader discern the implications.

But God is sovereign even over darkness, and small deeds of faithfulness make a difference. This Present Darkness’s publication may have seemed insignificant at the time, but its effect—much like that of its heroes—shook the status quo to its core.

Best for: Adults seeking a spectacular paranormal thriller with spiritual insight.

Discern: Strong stylized and bloody violence; frightening and disturbing imagery; sexual innuendo; references to sexual assault; depictions of occult practices.

The Visitation

E. Stephen Burnett

After his double-hit Darkness novels about angels versus demons, followed by two more suspense thrillers in the 1990s,

Frank E. Peretti chose to get more personal. His 1999 contemporary novel The Visitation instead focuses on a person’s inner demons, specifically those of a former Pentecostal pastor in Washington state.

This is burned-out pastor Travis Jordan. After a mysterious stranger comes to the town of Antioch, Washington, Travis is forced to review his past. After all, this kindly stranger, Brandon Nichols, seems to know all about Travis. Even worse, Nichols claims to be “a new, improved version of Jesus.” He has endless charisma. He can perform real healings. He preaches love and tolerance. Naturally, he soon forms a religious movement that pulls in many believers, excepting Jordan and others.

All along, this “messiah” has a personal mission to ensnare Jordan himself. Nichols is convinced their stories are the same: that they both mistrust the Lord.

Thus begins a series of doctrinal deceptions and battles in a small town, woven with chapter-length flashbacks to Travis’s past struggles and life changes. Travis is forced to wrestle with the teachings of his youth, church authority abuses, why God does and does not heal friends and church members, and most of all, the real Jesus.

Peretti’s heroes confront their own flaws, yet give no ground to false teachings both inside and outside the Church. In fact, unlike other Christian-made novels, this one has named denominations, such as Pentecostals, Baptists, and Lutherans. Without preachiness, yet with grace and gentle humor, Peretti shows these saints’ excesses and where they get things mostly right—a hyper-realized version of the real world.

A great theology book can debunk false doctrines or tell about true ones, such as who Jesus is and why we must follow and worship him. Yet it takes a great fiction book to show how the real world challenges one’s faith, and to awaken new and unique passions to know and follow the true Jesus. The Visitation is one of the best.

Best for: Older teen and adult readers who like suspense with supernatural edges.

Discern: Comedic and serious presentation of charismatic gifts (specifically among Pentecostals), spiritual abuse, fake versus real healings, teen infatuation and romance, false christ with unexplained (demonic?) powers, threats or violence, and unanswered questions about why the real Jesus Christ does what he does.

Phantastes

reviewed by Audie Thacker

For anyone who thinks a trip to fairyland would be a fun romp, George MacDonald’s Phantastes (1858) serves a sobering reminder: fairyland is a dangerous place. It’s filled with all manner of threats lurking just beyond view, or even hiding behind that object right in front of you, which you think is so beautiful.

The story recounts the travails of a young man, Anodos, as he journeys across a fairy landscape. He meets a murderous tree, a fallen knight, and a sleeping beauty, while he is being haunted by his own shadow.

Now more than 150 years old, this book harkens back to the arcane in style as well as substance. It’s not necessarily a breezy read, and it isn’t an example of typical modern storytelling. But readers who dare venture with Anodos into this fantastical land will certainly not return unchanged.

Best for: Adult readers.

Discern: Few overt Christian elements appear in the story, and MacDonald himself had some arguably unorthodox theological ideas that readers may want to discuss.

- Editor’s note: This first name spelling has been corrected since the original publication. ↩

[…] cover story: “The Best of Christian Fantasy,” in which our well-read review team chooses their favorite Christian-made […]

[…] And I’ll end with this bit from the more recent Lorehaven magazine review of Oxygen: […]