Behold the Fantastic Purposes of ‘The Chosen’ and Other Great Biblical Fiction

Christians are feeling inspired, confused, fearful, delighted, and challenged because of one biblical fiction TV series, The Chosen.1

Fans of this series (I’m a big fan of it myself!) often praise its many blessings. The Chosen is a fan-funded streaming drama.2 Its mission is to reenact Jesus Christ’s ministry, as seen through the lives of his apostles and others who knew him best, such as Peter, Andrew, Matthew, Nicodemus, and Mary Magdalene.

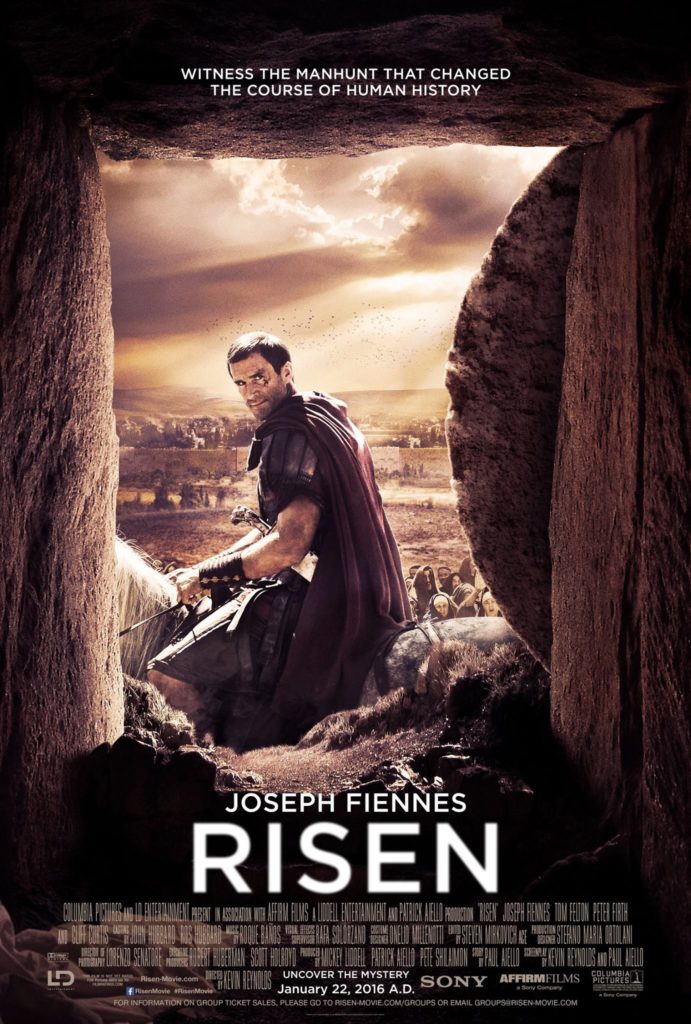

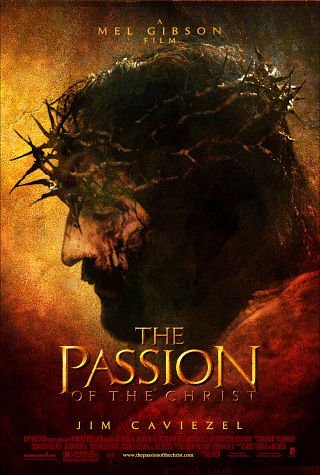

Fans of The Chosen also know this series is a kind of story (also called a genre) called biblical fiction. So are many biblical fiction films, such as Risen (2016) and Paul, Apostle of Christ (2018) as well as Mel Gibson’s blockbuster film The Passion of the Christ (2004) and the classic Bible epics Ben-Hur (1959) and The Ten Commandments (1956). Christian-made stories for kids also feature biblical fiction! (I cite a few later.)

Babel from Brennan S. McPherson explores a fictionalized version of the post-Flood world, continuing the Fall of Man series from his novels Cain and Flood.

Meanwhile, Christian novelists pen tales set in biblical history. These include older authors like Lew Wallace and Lloyd C. Douglas as well as many storytellers in the present, such as Brennan McPherson’s Fall of Man series, as well as Randy Ingermanson’s City of God series and newer Crown of Thorns series. Newer authors may even add elements to help readers feel more at home in these ancient times, such as romance or even time travel.

However, the idea of biblical fiction also raises many questions among Christians.

For example, I’ve seen many questions in The Chosen fan forums. (These are now growing in popularity since the series started gaining more fans, around Easter 2020.) After fans read biblical fiction books or watch biblical fiction films, they ask:

- What type of story is this?

- How does it differ from Scripture?

- Should these differences cause us alarm?

- What about Christians who might confuse reality and fiction?

Some fans of biblical fiction feel certain emotions, like viewers who say they feel moved to love Jesus more or read the Bible more. One viewer, however, said she felt a “check in her spirit,” like a divine “prompting” to avoid the show. Still others may not be certain how to describe feelings they may be having for the first time.

At best, we are like the Ethiopian eunuch who got hold of the book of Isaiah, but needed a guide to understand what he was reading (Acts 8:26–40).

Toward that end, I have compiled twelve top questions Christians should ask about any kind of biblical fiction, including The Chosen.3

During this journey, let’s follow the apostle Paul’s wisdom: “For everything created by God is good, and nothing is to be rejected if it is received with thanksgiving, for it is made holy by the word of God and prayer” (1 Timothy 4:4–5, ESV).

Risen (2016) stars Joseph Fiennes as the cynical yet earnest Roman centurion Clavius, who is assigned to investigate the disappearance of Jesus’s body.

1. What do we mean by “biblical fiction”?

To understand the label of biblical fiction, let’s define it briefly and carefully.

Let’s start by accepting what biblical fiction is not meant to be.

- It’s not a replacement for Scripture.

- It’s not a sermon or textbook about Scripture.

- It’s not an exact, verse-by-verse re-enactment of Scripture.

- It’s not only focused on historical figures like Jesus, Mary, or Paul.

Instead, let’s understand and accept what biblical fiction is meant to be.

- It is set in ancient times as described by the Bible.

- It often involves historical people that Scripture describes.

- It often explores plotlines and specific events we read in Scripture.

- It usually adds situations, people, or events we don’t read in Scripture

Based on these points, let’s build a working description of biblical fiction:

Biblical fiction is set in biblical times and often involves real-world people, plotlines, and events we read about in the Scripture, while also adding people, plotlines, and events that we do not read about in Scripture.

Let’s accept the story “rules” for biblical fiction.

Viewers (and readers, etc.) should recognize this definition of what biblical fiction is. Then we must adjust our expectations. That’s just part of good interpretation practice, whether we read the Bible or engage with any person’s creative work.

For example, if we study the Psalms, we don’t expect records about battles or direct doctrine about the gospel. Instead, we must know the Psalm “rules.” This is why Christians must value the knowledge of pastors and Bible scholars who have (or should have!) had training about biblical exegesis and worldview. And if we read a graphic novel, we would not be surprised to see art panels and speech balloons.

Let’s also respect the intentions of a story’s creators.

Another question related to the definition of “biblical fiction” might go like this:

If people tell me, “This thing here is biblical fiction,” should I believe them?

Brief answer: yes.

Longer answer: In general, Christians must respect the stated intentions of people who make a thing, like a story or TV show. That’s just good interpretation, which theologians call hermeneutics.4

By contrast, if we read a Bible book whose author (and capital-A Author, God!) is clearly saying, “I meant this part to be read as real history,” then it’s wrong for us to start thinking, “No, instead I believe this book is only full of non-literal symbolism.”

Similarly, if we watch a biblical fiction movie whose maker says, “This is biblical fiction,” we ought not react as if the movie-maker said, “I’m going to preach a sermon about the Bible.” Nor should we react as if the movie-maker said, “This biblical fiction is meant to replace the Bible. I think my fictional events are real.”

If we respect God as the Author of Scripture, we must also respect our human neighbors who make other kinds of stories, whether or not they are Christians.

(The only exception would be if we have serious grounds to doubt their word. But if we started off doubting everyone like this, we may end up slandering other people. This, unlike the enjoyment of good biblical fiction, is an actual sin God condemns.)

The Young Messiah (2016) was based on an Anne Rice novel and borrowed from early legends about Jesus’s childhood, yet emphasized his biblical deity and humanity.

2. What is the purpose of any fiction?

We have a definition of biblical fiction. But what’s the point of having any fiction in the first place? Can’t we just get along with sermons, textbooks, and biographies?

We live in the real world, which includes fiction.

Most Christians understand we can’t ignore the reality of fiction! That means we cannot want to escape to an imaginary world where people don’t care for stories and instead only want to be “practical.” Instead, we must live in the real world.

(Imagine if we did try to retreat to that kind of imaginary world. If we did, we would only expose the fact that all have imaginations and like to picture crazy worlds!)

God gave us the gift of imagination and culture-making.

Christians who study the big ideas of Scripture recognize that God has given all people the gift of imagination. It’s part of the “cultural mandate” of Genesis 1:28.5 Here, God commands Adam and Eve to grow their families and be good stewards of the Earth. They must reflect God in all they do, including his creative nature.

People cannot obey this command of God unless they use their gifts of imagination.

Even after the Fall, Scripture shows examples of people using imagination.

Yes, the first humans fell into sin. This is followed by Jesus’s heroic rescue mission across the centuries to redeem his people. Despite this, the Bible tells about people (God’s people and others!) using their imaginations to steward the Earth.

God himself calls his own people to build architectural marvels like the Tabernacle (and later, the Temple). In fact, the first person whom God described as “filled with the Spirit of God” is a creative artisan named Bezalel; the Bible says God gave him “skill, with intelligence, with knowledge, and with all craftsmanship” (Exodus 35:31).

Old Testament prophets performed crazy stunts to warn people about God’s wrath.

Jesus told parables, fictional stories, to reveal (or hide!) Kingdom truth to people.

And of course, many others were inspired by the Holy Spirit to write the Bible itself.

Now (and forever?), Christians can use our imaginations for God’s glory.

Today, Christians use God’s creative gifts to imagine things that aren’t real for the glory of God. Sometimes we can make those creations physical (such as new church buildings, paintings, or music). Other times, those creations stay non-physical, such as the characters from novels who may feel “real” in our heads and hearts.

Either way, if we are in Christ, we have started our journey of redemption. On the way, we can resist our sin and start recovering godly ways to enjoy God’s gifts—not just gifts like Bible reading and prayer, but his gift of enjoying our imaginations.

In the future, at the Resurrection, God will surely redeem his people’s imaginations. That way, we can fully worship him—with no sin left!—by making amazing things.

The Passion of the Christ (2004), directed by Mel Gibson, polarized secular audiences yet enthralled Christians with its brutal R-rated portrayal of Jesus’s suffering and death.

3. Should we use fiction mainly as a tool for other ends?

When Christians enjoy fiction, they often speak in terms of finding the story useful in some way. They will say, “This is a great method for introducing nonbelievers to the Bible,” or, “This is a fantastic tool for helping kids understand moral truths.”

To be sure, it’s good to learn the gospel, morality, or other knowledge via stories.

However, if we overemphasize these purposes, we miss fiction’s greatest purpose.

Fiction can glorify God even if it isn’t an overt “teaching tool.”

Stories are not just “practical tools” for more important goals, like evangelism or moral teaching. Fiction is not first valuable because it helps us feel strong and very human feelings. Instead, fiction glorifies God first by reflecting his creativity in the imagination that he has given us (and remember, that imagination gift was his idea).

Yes, good fiction does help teach us, not first by telling, but by showing.

Stories don’t just teach us things in the way that a sermon or classroom instructor would teach us things. They don’t just speak to our heads, but to our hearts.

Stories don’t only tell about simple facts or moral principles. Instead, good stories include facts and moral principles and show them in action, using imaginary people (or animals, or any thinking creatures). Instead of us getting the facts or morals told to us, we imagine what happens when people use these ideas to make decisions. And even better, the really, really good stories honor Scripture in some way, when they show what happens to heroes who learn to act well, versus villains who do not.

If we try to make fiction a “practical tool,” we actually risk misusing fiction.

If we try to skip this great purpose of stories, and try to use stories as mere tools for other ends, we could miss that creative-God-reflecting purpose of stories.

Worse still, we could miss out on learning (and teaching others!) most effectively thanks to stories’ true power. Again: stories do “teach” us, but not like lecturers. They help us imagine life alongside fictional heroes whom we come to love.

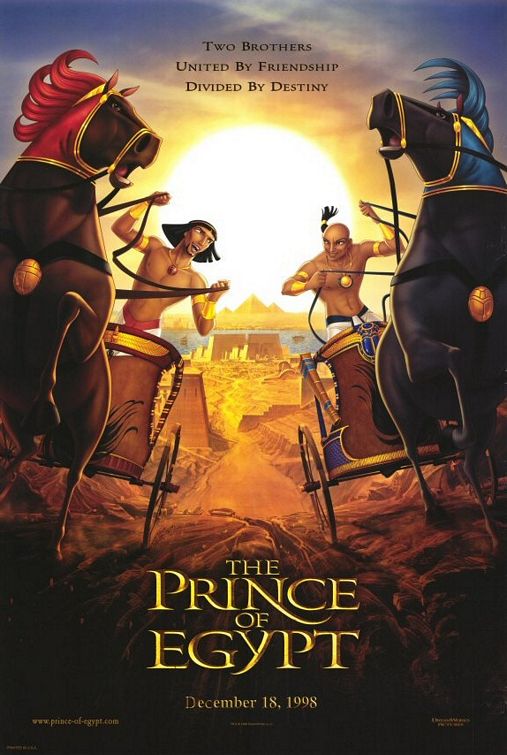

The Prince of Egypt (1998), Dreamworks’ retelling of the biblical Exodus, changed some details of Moses’s story yet still presented God in all his infinite majesty.

4. What is the purpose of biblical fiction?

If we believe it’s okay and even good to enjoy fiction, what about biblical fiction uniquely? Why blend the non-reality of fiction with the reality of true events?

First, we must answer this as individuals (and only later talk about the kids).

At this point, many Christians may have an impulse to think mainly about other people: that is, impressionable children, or others who have trouble sorting reality from unreality. (Those are real issues; see question 12.) But first, we must presume that we’re all grown-ups here, who can discern the differences between the two.

If, however, we don’t feel at least partly comfortable discerning at this level, we’re likely not qualified to help the kids learn to discern TV or other fiction! It would be as if we tried to teach a teenager to drive—while we’re still in middle school.

In the rest of these questions, we will focus on us as Christian grown-ups, who are accountable before God for ourselves. Only then will it be time to consider the kids.

Biblical fiction is a type of story called historical fiction.

People, including many Christians, have created many different types of stories, such as contemporary, mystery, suspense, romance, action/adventure, and beyond. (My personal favorites are fantasy, science fiction, and of course biblical fiction!)

One huge field of fiction is historical fiction. This type of fiction places fictional heroes, events, and storylines into historical settings.

Historical fiction writers explore eras like the Civil War in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind, or the evacuation of French beaches in Christopher Nolan’s film Dunkirk. Sometimes these stories interact with historical persons; sometimes not.

Good historical fiction is a great way to connect our hearts with our history.

Either way, these writers help us use our imaginations to explore historical eras long after those eras are past. Creators of historical fiction must also assume that readers can do their homework and know the difference. (For instance, there never was a real person called Scarlett O’Hara in Georgia, but there was a real Civil War.)

Historical fiction opens history to our imaginations, helping these eras come to life in our hearts. That way, our stories aren’t always stuck in the present.6

When we know the purpose of historical fiction, we’re one step away from knowing the purpose of biblical fiction. After all, biblical fiction is just another kind of historical fiction, for Christians who (rightly) believe the Bible describes real history. Nowhere does Scripture forbid us from exploring stories set in history, any more than it forbids fiction set in our time. Instead, Scripture gives us a positive picture of God-glorifying imagination, and even has its own “biblical fiction”: Jesus’s parables!

Any kind of fiction, whether it is modern or historical, is saying to us, “This didn’t happen, but what if it did?” Christians should accept this as a fiction “rule.”

Coming this Monday, May 10, in this Discerning Biblical Fiction series: Is biblical fiction “inspired” by God? Why does imagination feel so inspirational and even spiritual? Explore how biblical fiction isn’t inspired by God, but it can inspire our imaginations.

- My thanks to biblical fiction author Brennan S. McPherson for detailed feedback on an early draft of this article series! ↩

- As of this date, The Chosen is now in its second reason. Creators plan several seasons to explore Christ’s life, death, and resurrection, and how he changes his closest followers. ↩

- Please note that in this work, I use the words stories and fiction interchangeably. This article series also tends to focus on biblical fiction movies and shows, but everything here can also apply to biblical fiction that appears in novel or other written form. ↩

- Webster’s offers this definition for hermeneutics: “the study of the methodological principles of interpretation (as of the Bible).” ↩

- See “What Is the cultural mandate? Who is it given to?” undated article, 9marks.org. ↩

- Of course, our modern fiction would just become historical fiction to future readers anyway! ↩

Excellent read!