Duke Leto of ‘Dune’ Shows How Christians Can Live with Nobility in a Hostile World

Of all the films the pandemic delayed, Dennis Villeneuve’s Dune: Part One topped my anticipation list. This fall, the final film did not disappoint me. Gorgeous shots showed plenty of spectacle, making this one of the best-looking sci-fi films I’ve seen. Combine that with stellar acting and fantastic adaption (despite some skipped scenes from the book), and this made one of the best films I’ve seen this year.

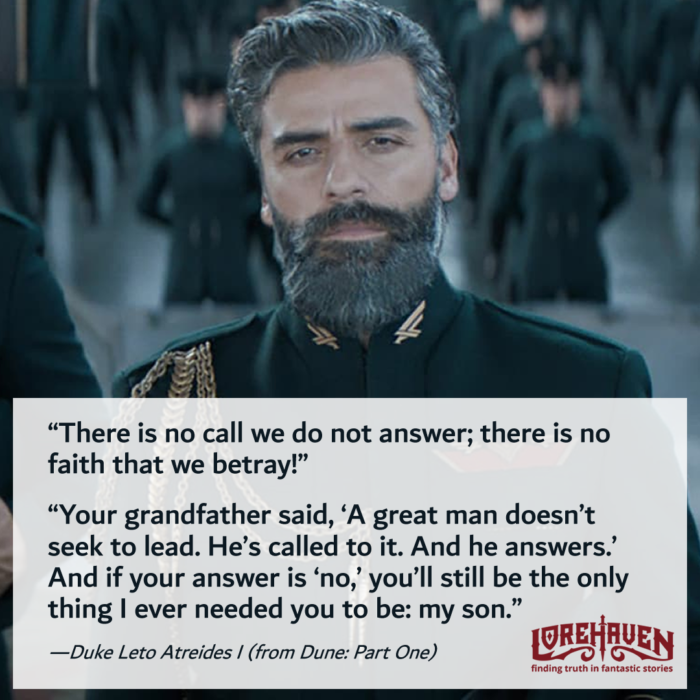

Still, I didn’t notice one of the adaptation choices until my second viewing. Dune spotlights the noble character of House Atreides, and specifically Duke Leto (played by Oscar Isaac). From the start, Dune consistently elevates Duke Leto’s virtue in ways that can’t help attracting viewers to him and his high ideals.

I’ve reflected on this, and on a recent Fantastical Truth episode, and found that Duke Leto happens to give Christians a model for how to live in a negative world.

The world we live in

In the episode “Can We Positively Engage Culture in a Negative World?”, E. Stephen Burnett and Zackary Russell spoke with Esther O’Reilly about different ways the world views Christianity. They argued that the world’s past positive or even neutral treatments of Christianity have, after 2014, transformed into a negative treatment.

I might have friendly disagreements with my colleagues on whether we live in a negative world. That’s because I subscribe more to a model of “dual cultures in one nation.” While one culture views Christianity as a social negative, a competing culture still views Christianity as a socially neutral force. That competing culture still holds much influence. As a result, while we see more negative spaces today than we did thirty years ago, I would question if we’re living in a negative world.

However, I certainly agree with my colleagues that Christians will often engage with negative spaces throughout our lives—more so today than thirty years ago. And this raises questions for how we should interact with negative spaces, where people treat Christianity as a social evil. For one answer, I look to the fictional Duke.

The negative world of Dune (beware spoilers)

Duke Leto faces a hostile world in Dune, not because of his beliefs but because of his political power. He faces many powerful opponents, including the evil House Harkonnen, the secretive Bene Gesserit, and even the emperor himself. Leto stays conscious of his enemies’ conspiracies and acts with caution (even if he’s unaware how deep the emperor’s betrayal will go).

Duke Leto faces a hostile world in Dune, not because of his beliefs but because of his political power. He faces many powerful opponents, including the evil House Harkonnen, the secretive Bene Gesserit, and even the emperor himself. Leto stays conscious of his enemies’ conspiracies and acts with caution (even if he’s unaware how deep the emperor’s betrayal will go).

One could imagine an alternate world where Leto reacts to his enemies’ pressure with similar murderous and treacherous tactics, just to survive. Yet Villeneuve emphasizes Leto’s crowning nobility, even in the face of nefarious adversaries.

Early in the film, Leto proclaims, “There is no call we do not answer; there is no faith that we betray!” Every time Leto appears onscreen, his posture reinforces his resolute nature. In a pivotal conversation, Leto tells his son, Paul: “Your grandfather said, ‘A great man doesn’t seek to lead. He’s called to it. And he answers.’ And if your answer is ‘no,’ you’ll still be the only thing I ever needed you to be: my son.”

Later after House Atreides moves to assume control over the desert planet Arrakis, Leto repeatedly reveals his nobility in his dealings with the native Fremen. The planet’s new duke desires to treat them as allies. He deters his men who take offence at their customs. When a giant sand worm attacks Leto’s spice mining crew, Leto values the miners’ lives over the profitable spice.

No matter how much House Harkonnen may sabotage House Atreides, Leto insists on valuing life over spice profits, and nobility over pragmatism.

Christians can imitate Duke Leto’s moral example.

Emulating Duke Leto’s nobility

When we’re living in a hostile world, we’re often tempted to adopt our enemies’ methods and do whatever it takes to win. After all, if they’re using vicious tactics that bring victory, don’t we need to adopt similar strategies to survive?

Leto shows the example of a better path.

To some extent, I’m unable to explain with words how we should emulate Leto. Situations vary. Stories shouldn’t be reduced to specific theses. The best way we can enjoy Dune: Part One and grow as people is to reflect on Leto’s character, hold his example in our mind, and use this as inspiration to act likewise.

Still, I might say this. In a world where we see Harkonnen soldiers storming over the horizon, we can choose to imitate Leto. We can choose love over manipulation, like the duke did with Paul. We can prize lives over gain, like he did with the miners. And we can always seek to win over neutral forces, as Leto did with the Fremen.

Such examples give spice to our moral imagination, bringing the vision we need for imagining moral living in an uncertain future

Duke Leto may have lost the battle, but won the nobility war

Dune fans might raise a challenge: “But wait. Didn’t Leto fail?” Of course, the film ends with Leto stripped and killed. Why then would we adopt him as a role model?

Dune fans might raise a challenge: “But wait. Didn’t Leto fail?” Of course, the film ends with Leto stripped and killed. Why then would we adopt him as a role model?

I would argue that Leto’s fate is irrelevant. Scripture yet calls us to do what is right regardless of the consequences. To be sure, Leto dies—but he dies while holding his dignity. He can be stripped of his clothes. But he can’t be stripped of his honor—an honor that still emanates from him even when wears nothing else. Our calling is to act like Christ and trust God with the results.

But it’s also true that we need more than nobility to live in a hostile world. We also need cunning. In the film, Leto may not display much cunning. But book-Leto does.

That’s why, just like Dune: Part One, we’ll need a sequel (next week) exploring how book-Leto reveals cunning strategies for living in a negative world. But for now, let’s focus on film-Leto’s noble example. How could we follow Leto’s example in our negative spaces? How might we hold ourselves, with unapologetic confidence in our own actions and character, and to refuse to stoop to the enemy’s game?

Duke Leto helps reflect how Christians can win “desert power”—even when we lose.

But did Paul really follow his dad’s example when he became the titular Dune Messiah? (Granted, I haven’t read beyond the first book because it didn’t hold that much interest for me.)

The worldbuilding of Dune? S-tier, which is why it’s survived so long. The characters of Dune? Mostly one-note pieces of blah moved around to suit the plot. Leto isn’t a character, he’s a SYMBOLISM, unfortunately.

The book is more complicated than the film on this front (which is part of what I’ll be getting into in my next article), but a major part of Paul’s struggle in the book /is/ that he wants to win /without/ initiating a universe-wide jihad. So I would argue that his character does retain a lot of this nobility in the original Dune. My understanding is that he might lose some of this in the sequel, but I haven’t had the time to read that either. Either way, though, I’m not trying to argue in this article that Herbert was necessarily intending these themes as he wrote or that these are necessarily the primary thematic points that Dune makes–simply that this is one relevant application we can make when focusing on the example of Leto.

Yes, we need a sequel. Also I need to read the book. I just came back from watching Dune today (it’s finally out in Australia). I loved it and I’m going into what various people are saying about the themes. Very glad to see that you’re talking about it.