How Great Biblical Fiction Adds Extra-Biblical Images Yet Honors God’s Word

We have already seen in this Discerning Biblical Fiction series that biblical fiction has fantastic purposes to help God’s people worship Jesus (part 1), and yet God does not inspire biblical fiction in the same way he has inspired the Bible (part 2).

God’s word says, “All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work” (2 Timothy 3:16–17). God’s word can inspire us to perform these good works, including gifts like biblical fiction! But our works do not come from the same “God-breathed” inspiration of the Holy Spirit.

Thus, because many Christians confuse the terms, I think it’s best to avoid using words like “inspired” or phrases like “God told me to write this play/song/story” about our creations. God can work providentially in how we exercise his gifts. Still, his gift of imagination is a powerful yet ordinary way we glorify him.

When we enjoy Christian-made artworks, we aren’t hearing, reading, or watching new books of the Bible. God’s word is still our ultimate standard—and his word never teaches us to expect new acts of “God-breathed” inspiration like itself.

That difference between biblical and unbiblical is crucial. It’s the difference between created works that God directly inspired, by means of human writers, and created works made by people. Can God “nudge” and providentially shape our creations, or set up amazing opportunities for us to minister creatively to others? Absolutely. Does this place manmade creative works at the level of Scripture? Absolutely not.1

Like any fiction, biblical fiction includes biblical ideas and ideas that aren’t biblical. But among not-so-biblical ideas, we find another difference. That’s the difference between ideas that are unbiblical (opposed to Scripture) and simply extra-biblical. If we don’t discern the difference, we could end up condemning a biblical fiction story for being unbiblical when it’s simply doing extra-biblical speculation. Or we could think a story is just being extra-biblical, when it’s actually opposing God’s word.

Joseph Fiennes portrays Roman tribune Clavius, an extra-biblical but not unbiblical character, in the biblical fiction drama Risen (2016).

7. What’s the difference between ‘un-biblical’ and ‘extra-biblical’?

Does biblical fiction include ideas that we could call unbiblical?

The idea of including fictional characters in biblical accounts (such as Judah Ben-Hur in Ben-Hur, or Clavius from Risen) strikes many Christians as contrary to Scripture.

Also, because all biblical fiction must also adapt the Bible for their stories, you will find differences between the Bible and the biblical fiction work. Even in a movie that tries to reenact events exactly according to the Bible (such as The Gospel of John in 2003), the creators include visuals, people, and places Scripture doesn’t mention.

The Chosen goes still further. In the series’ very first episode, we meet a woman called “Lilith” whose true name (spoiler alert!) turns out to be Mary Magdalene. The show’s creators also explore fictional stories about the biblical apostles. We see Peter’s desperation as he turns toward shady tactics to pay down his debt. We find that Matthew is at first a man who prefers math, logic, and keeping to himself.

It’s good to ask of any biblical fiction, “Wait. Are these imaginations in the Bible?”

Short answer: No, these imaginations aren’t in the Bible—and that’s okay!

Remember, if we enjoy biblical fiction, we must keep in mind the story’s “rules.”

If we hear a pastor preach a sermon, we’re right to expect that he will stick to the text he’s helping us study.2 However, if we enjoy biblical fiction, we should expect imaginary people and storylines, mixed with true events Scripture describes. If biblical fiction did not include these things, it would not be fiction!

Long answer: Let’s discern the difference between unbiblical and extra-biblical.

Let’s be careful when we call a biblical fiction’s character, or scene, or anything else “unbiblical.” If an idea is unbiblical, then that idea is actively opposed to something God has told us in his word about himself, such as his nature, his law, or his gospel.

If the biblical fiction we enjoy is a good story, it will be made by Christians who want to be faithful to Scripture while also adapting the story. If so, they will avoid being unbiblical. No fictional idea they include will contradict the Bible, certainly not in vital ways.

Instead of calling these stories “unbiblical,” a better word is extra-biblical. This means ideas that don’t contradict Scripture yet are not found in Scripture.

Let’s explore more specific examples over the next two questions.

8. Can biblical fiction include extra-biblical words and dialogue?

What then about moments in biblical fiction in which biblical characters, especially Jesus himself, speak in ways that aren’t verbatim from the Scripture? For example:

- In The Chosen, characters speak in very familiar and contemporary ways. When Nicodemus says he’s shocked by Mary’s recovery, she says, “That makes two of us.” Later, Jesus himself tells his new followers, “Listen, if we are going to have a question-and-answer session every time we do something you’re not used to, it’s going to be an annoying time together for all of us. Get used to different.”

- In The Passion of the Christ (2004), most of the film is performed in the ancient language of Aramaic. Still, characters speak in extra-biblical and very modern ways. Viewers may recall a lighter scene in which a young Jesus famously makes a table with legs, and Mary suggests to him, “That will never catch on.”

- In The Ten Commandments (1956), Moses’s Egyptian ex-girlfriend Nefretiri tries to tempt Moses back to the dark side. She asks of Moses’s wife, “Are her lips chafed and dry as the desert sand, or are they moist and red like a pomegranate?”

Sometimes writers of biblical fiction may try to imitate biblical language. But many Christians can tell the difference. Should these different words bother us?

Download the official series app at TheChosen.tv, if you have not already.

It helps to recall that every Bible version is always translating language.

Even in our Bible versions today, the translators have made word choices to help all readers understand the Scripture in their own languages.

- Many versions translate a Hebrew name for God, “YAHWEH,” to “the LORD.”

- An ancient simile about the center of our being gets translated into “the heart.”

- In the 1611 King James Version, translators used a then-modern phrase “fetched a compass” to describe the path of Paul’s missionary group (see Acts 28:13, KJV).

Biblically faithful scholars also point out that the New Testament’s human authors relied on truthful memory to recall Jesus’s teachings. Jesus himself would have been called Yeshua in original Hebrew, and he probably taught in the common language of Aramaic. As the New Testament writers wrote (inspired by God!), they translated all this into a form of Greek, making sure more people would read their gospels.

Biblical fiction “translates” the Bible and also “translates” the story.

Let’s also remember that our “rules” for biblical fiction include permission for the story to adapt and ask “what if?” about the Scripture, to help fit the story’s needs.

In The Ten Commandments, the creators were “translating” the story, and not just by reading Bible versions. They also “translated” the story for expectations of 1950s audiences (who did not mind some over-the-top acting and colorful dialogue!).

In Risen (2016), the creators follow a fictional Roman centurion named Clavius. He must go on a mission after Jesus Christ’s body goes missing. This way, the story “translates” the life and death of Jesus as viewed by a pagan Roman soldier. It also “translates” the story into a modern genre we know: the investigation of a mystery.

Similarly, The Chosen’s creators aim to look, feel, and sound like any other historical drama you might find on other streaming services. It fits these story “rules” to have characters speak in modern ways. It fits rational story expectations to translate most Hebrew names to their original and biblical Greek equivalents, because this is how most audience members would recognize Jesus, Peter, Mary, and others.

9. Can biblical fiction include extra-biblical people and storylines?

One Christian radio host admitted he had not seen The Chosen.3 But after he read reviews of the series, he asked if the series might contradict Scripture by, say, introducing a side character called Tamar. She and her friends help a disabled man by breaking through a roof to access Jesus (see Mark 2), but no one named Tamar appears in the biblical record. The host also asked why The Chosen portrays Mary Magdalene joining the apostles, because Scripture doesn’t say Mary did this.

Going beyond words and translation choices, what about these kinds of apparent changes in biblical fiction that may not sound like the biblical source material?

Many moments like this are extra-biblical, not necessarily unbiblical.

Let’s take another example from The Chosen. The series presents the apostle Matthew as a social outcast. This choice is based on a good guess, because he was a tax collector. Even today we make jokes about tax collectors, but for first-century Jews, a person who worked with the Romans was even worse! The writers, however, add several extra-biblical ideas to help us follow Matthew’s life. He tracks numbers and he is very focused on logic. At first, he dislikes germs or making direct eye contact. In fact, the creators even suggest their Matthew is on the autism spectrum.

These aren’t unbiblical details. Based on Matthew’s later detailing of Jesus’s ministry, and his original tax-collector job, we can ask: what if Matthew was like this for these reasons? Scripture doesn’t say one way or another. So these are extra-biblical ideas.

Similarly, we shouldn’t even hint that The Chosen may be unbiblical simply because the series imagines new characters, such as Tamar, and makes them part of the story. Nor is the story unbiblical for showing Mary joining the apostles on at least some of their journey. The gospels do refer to Mary as Jesus’s follower and often refers to others following Jesus, of whom the twelve apostles form a core group.

Again, the word for these storylines is not unbiblical, but extra-biblical. This is just what we should expect from a story that aims to be biblical fiction (not a sermon).

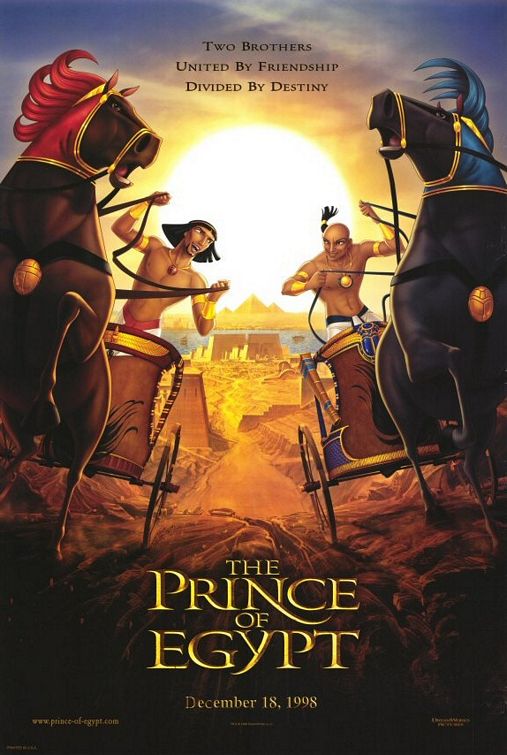

In The Prince of Egypt (1998), you can actually see Pharaoh decide to harden his heart. Yet this character also carries motives and says things that aren’t recorded in Scripture.

Other biblical fiction works do contradict Scripture, but in nonessential ways.

To be sure, some biblical fiction doesn’t always make things this easy. Two major film adaptations of the Exodus account, The Ten Commandments (1956) and the animated epic The Prince of Egypt (1998) make Moses an adopted brother to the future Pharaoh, called Rameses. But the Bible doesn’t say they were brothers and doesn’t name this Pharaoh. Technically, these changes aren’t contrary to Scripture! But other changes go further. Both films add major changes to Moses’s life, such as giving him an Egyptian girlfriend (Commandments) or making his brother Aaron into a skeptic rather than a spokesman (Prince). How should we think about this?

Of course, to this day, some Christians who have seen either movie may be convinced that Scripture teaches Moses and Rameses grew up as brothers.4 But for other viewers, bigger changes like these are actually easier to discern than the smaller changes.

In either case, these changes are not necessarily intended to weaken a truth from the Bible. Rather, they’re meant to raise the stakes of the story, such as by giving Moses even greater challenge when he relays God’s command to Pharaoh, “Let my people go!” These changes may concern some Christians (and if they concern you, that’s a fact to consider). Yet they don’t necessarily interfere with the story’s heart.

In both films, God calls Moses away from his life as a prince of Egypt into his role as leader of Israel. Each film portrays God himself with rightful majesty and holiness. In each film, God clearly reveals his omnipotent will. He performs real miracles to punish the Pharaoh for his hard-heartedness and make him let the people go.

To many Christians, that makes a big difference. Despite smaller changes to the human figures in the Scripture’s account, these stories don’t mess with God himself. Rather, they show God and his supernatural miracles according to the Bible, without contradicting who God is, what his nature is, and what actions he did. They honor the biblical God as the unquestioned Ruler over all onscreen reality.

The Bible itself uses unreal “what if?” images to help us grasp real truth.

Sometimes we are so greatly blessed by an imaginative idea that we can see biblical reality more clearly. In some strange way, the “untruth” shines more light on truth.

Scripture itself includes many imagined pictures that illustrate real truth, such as Jesus’s parables and other symbols. Some are based on literal events, and some are wholly imaginary. Either way, we read Scripture as it’s meant to be read—including its images. For example, Revelation 19:11–16 presents a thrilling vision of Jesus Christ on a white horse at his second coming to Earth. Verse 15 says, “From his mouth comes a sharp sword.” Amidst any literal meanings about Christ’s second coming, this is likely a symbol, an image, about the power of Jesus’s word.

Biblical fiction also uses unreal “what if?” ideas to help us grasp real truth.

In Risen, Pilate hires Roman centurion Clavius to investigate the disappearance of Jesus’s body. Clavius questions the disciples and others, certain that Jesus’s body is being hidden somewhere. Then, during a Roman raid, Clavius opens the door to an upper room—and finds a very resurrected Jesus talking with his disciples. Thanks to this fictional scene, audiences can “re-experience” what it must have been like to find this dead Messiah suddenly alive again. Then we can take those feelings and, when we read the New Testament, enjoy this truth almost as if for the first time.

The Prince of Egypt shares a fully animated-musical version of the Exodus epic, which requires many dramatic elements. Characters break into song, and actions are carefully planned to match the film’s soundtrack (and vice-versa). In one climactic moment, Egyptian soldiers have pinned the Israelites against the Red Sea. The story does not follow all God’s instructions in Exodus 14, and condenses other details. Instead, Moses silently wades into the ocean. He lifts his staff. He hears an echo of God’s promise from before, and then slams his staff into the ocean. Only then do the waters defy physics and miraculously rise into walls, as the Scripture says. But the silent moment, followed by Moses’s plunge of his staff into the water, serves to illustrate the suddenness and supernatural reality of God’s wonders.

Finally, The Chosen uses extra-biblical storylines from its very first episode onward to reflect a powerful reality about God’s sovereignty. The episode opens with a father teaching his young girl a promise found in Isaiah 43:1. This extra-biblical scene is an expansion on the story of Mary Magdalene. After she grows, we learn she is traumatized and even oppressed by evil spirits. No one can deliver her from this wretched “body of death”—until Jesus arrives. He’s just beginning his ministry, so no one knows who he is. Audiences might begin to wonder: how will Jesus show her that he is not only no threat, but her only salvation? In this extra-biblical yet powerful scene, Jesus slowly approaches Mary and begins to quote Isaiah 43:1:

. . . Thus says the LORD,

he who created you, O Jacob,

he who formed you, O Israel:

“Fear not, for I have redeemed you;

I have called you by name, you are mine.”

Mary falls into Jesus’s arms. She weeps with freedom and joy, having been set free from the pain of her trauma and demonic oppression. Again, Scripture doesn’t share how Jesus cast seven demons out of Mary (see Mark 16:9 and Luke 8:2). But this speculative scene still serves to illustrate many biblical truths all at once. Jesus:

- Has absolute, simple, and supernatural power over demons.

- Can heal people in an instant, even healing people’s suffering minds.

- Loves people, including outcasts who have been wounded by others.

- Comforts us, as he later will “wipe away every tear” (Revelation 21:4).

- Works perfectly with the Father, the same God as in the Old Testament.

- Fulfills (not replaces!) the Law of God as revealed in the Old Testament.

- Honors, knows, and perfectly quotes the text of God’s revealed word.

- Knows all things, including the verses we found meaningful as children.

- Has been working in his people’s lives to bring them into his epic Story.

- Sees any person he saves as part of the greater salvation of all Israel.

To this date, that scene ranks as many fans’ favorite moment in The Chosen series. These extra-biblical details do not detract from the Bible, but honor God’s truth.

Some biblical fiction shows an “elseworld” version of the Bible story.

Still, every once in a while, biblical fiction makes so many changes to details that it could qualify as what we could call an “elseworld” story.5

For instance, Noah (2014) reimagines the Genesis 6–9 epic in a way very unlike the Bible’s record. It changes many big details. Here, only Shem has a wife, instead of all Noah’s sons. During the flood, one stowaway actually sneaks onto the Ark. Oh, and also there are angelic rock monsters, who keep angry crowds from destroying the Ark.6

If the film made only those big changes, it would have showed a simple “what if?” kind of retelling in an alternate universe.7 But Noah did go further than that. So do other works of biblical fiction that change too much.

Noah (Russell Crowe) struggles to hear a frustratingly vague God’s commands in the film Noah (2014). Read our review at the original SpecFaith blog from Austin Gunderson.

To be clear, other biblical fiction goes too far in changing key details.

Noah (2014) also seems to have interfered with the true God’s character and actions to show its own vaguer version of God. In the Bible, God was grieved with mankind. He clearly communicated this to Noah along with plans for the Ark construction, to help humans and animals survive the catastrophe (Genesis 6). But the film’s version of God is never directly heard. Instead, this elseworld-God gives Noah a frightening vision of a flood. He “speaks” only in symbols and images about how to stay alive.

Of course, Noah’s creators may done this to add suspense by building a mystery of what God was actually doing in this “elseworld,” or to give Noah a challenge. But this change makes it look like God “speaks” only in unclear ways like this, rather than sharing the clear and understandable word that he truly gives his people.

Later, the film ends with a controversial scene in which this “elseworld” version of Noah considers killing children to ensure people don’t fill the Earth with sin. This is a provocative idea. But the film still shows God silent, unlike the true God we know.

By leaving God’s motives and words so vague, and by making Noah more angry with people, the film’s unbiblical ideas concerned many Christian viewers.

Another biblical fiction movie did more to show God in unbiblical ways. Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014) at first indicated a lot of promise. Early trailers seemed to show an action-adventure drama that would pit Moses versus Egypt, and help bring God’s miracles to onscreen life with modern special effects.8 Unfortunately, the film half-heartedly showed some plagues in Egypt, and later, basically ruined the parting of the Red Sea. Worse still, the movie infamously portrayed God as behaving like a spoiled and bratty little child. Perhaps they were trying to do something “artistic” here. But ultimately this came across as weird, confusing, and of course unbiblical.

Biblical fiction may change details, add characters, and even change up the order of events. But when the stories mess with God, that does risk slandering the Almighty.

It’s okay to discern biblical fiction that is unbiblical—just know the difference!

Christians will improve their discernment and their godly witness when they study the differences between extra-biblical and unbiblical ideas in biblical fiction. If we do, then we will have extra credibility when we point out what’s genuinely unbiblical.

To sum up, here is are seven common ways biblical fiction can act unbiblically:

- Showing biblical heroes as too “perfect,” when Scripture says otherwise.

- Showing biblical heroes as too flawed or evil, when Scripture says otherwise.

- Doubting or questioning the supernatural activity of God, such as in miracles.

- Presenting God as an idiot, or cruel, or childish, or unable to reveal his will.

- Overemphasizing Jesus’s human or divine nature, rather than showing both.

- Suggesting that God isn’t a Trinity, that is, three-divine-persons-yet-one-God.

- Hijacking a biblical story for social or political agendas, apart from the gospel.

Please note: None of these means mature Christians should not watch a story! It may still have some good qualities that make the artwork at least interesting (such as Noah in 2014). However, if we watch or even enjoy the story, we must find any unbiblical ideas for what they are—and always compare ideas with the true Story!

Coming this Monday, May 24, to in part 4 of this Discerning Biblical Fiction series: What if non-Christian creators help to make biblical fiction? What if we feel deep personal connections with these non-Christian creators, especially the creators, writers, and actors who share such incredible work? Finally, how can Christians respond with grace and truth whenever children or other Christians seem to be confusing biblical fiction with reality?

- The Chosen biblical drama series creator Dallas Jenkins addressed this issue in another public social-media conversation:

I’ve been asked multiple times about the show being “inspired.” I never claim the spiritual authority that comes from being “inspired by God,” but there have absolutely been many moments where something random and small came to me out of the blue that isn’t really in my skill set or normal process that ended up specifically impacting countless people spiritually and was way better than I normally am.

I’m myself wrestling with what that means.

In response, I remarked (lightly edited):

Even with smaller-scale creative acts, I’ve experienced this phenomenon. I call these acts of God’s providence. I think that He is indeed active in our imagination, and in the people he providentially places in our path who help us find ministry openings. But he not overriding meaningful human choice that comes from being his image-bearers whom God gives measures of Creator-reflecting will and creativity. I feel a little weird saying this, as a “Calvinist,” but still, there it is. I’m especially encouraged to hear this about The Chosen and other Christian-made creative works that truly bless others.

(Also, not sure if this relates, but I once had a very strong impression that if I wrote a certain novel, that would be a world-changing book and would be my first book published. I can confirm this wasn’t the case. So not all of those strong feelings actually play out.)

Bezalel is my example here. He’s the first man described in the Bible as “filled with the Spirit of God” and God at once directly describes this man as having God-given talent, providentially guided, yet with “ability and intelligence, with knowledge and all craftsmanship, to devise artistic designs” (see Exodus 31:1–11). I love this so much. Maybe it’s similar to how we “work out our own salvation” yet knowing God is working in us (Philippians 2:12). Is God working? Or are we working? Yes! (But it’s still best to reserve the word “inspiration” for Scripture.) ↩

- Still, most solid Christian pastors will sometimes include “what if?” questions in their sermons. One of my favorite examples is a sermon by British preacher Charles Spurgeon, in which he asked what Jesus may have felt at the high place where the Devil tempted him, in Matthew 4 (and Mark 4). He also speculated about the Devil’s tactics—and it takes a lot of holy imagination for Christians to fight such temptations! Spurgeon notes: “You are afraid as you stand on the brink of a cliff, afraid that you may fall over, and all the while a mad inclination to fall over may steal over you. It is strange, but then we are strange creatures.” See Charles Spurgeon, Spiritual Warfare in a Believer’s Life, edited by Robert Hall (Emerald Books, 1993), page 91. ↩

- See “A Chosen Review,” April 28, 2020, Wretched on YouTube. This video uses the word “review,” but that’s a poor label choice. To review a story, you need to have seen it. ↩

- For more about how Christians may accidentally accept fictional ideas as if they are in the Bible’s actual records, see my article “Exodus: Gods, Kings, and Evangelical Headcanon” at Christ and Pop Culture, August 19, 2014. ↩

- That word describes DC graphic novels that retell familiar stories with several details changed based on one or more “what if?” questions. For instance, the popular DC story Superman: Red Son imagines a universe in which baby Kal-El’s escape rocket didn’t land in Kansas, but in Soviet Russia. Marvel Comics has a similar feature, asking “What If?” ↩

- Interestingly, the film still reflects the truth that man was evil and deserved to be destroyed. It also showed the Flood as global, and many Christians will agree. ↩

- Christian creators have written similar stories, such as imagining what would happen if Jesus had waited until the twentieth century to be born in the world and do his ministry. ↩

- Before the movie released, I even argued that the film needed to keep these supernatural truths, at least to keep the story awesome. See my article “Will Exodus: Gods and Kings Fear the Fantastical?“, December 9, 2014, Christ and Pop Culture. ↩

Well said! Thanks for this thorough discussion of the importance of staying TRUE in fiction. I’m reminded of VeggieTales…and Adventures in Odyssey…my kids knew these were fantasy mixed with Bible, but still sometimes couldn’t recall which events were the Bible-actual and which were the Bible-fantasy. Maybe there’s some danger in the mix.

I think there’s much greater danger in giving children fantastical version of Biblical accounts, precisely because they are (and should be) learning what truth is. Parents should be discerning and not introduce confusion into their youngsters development.

Literally, this is the topic of part 5 of this series, arriving on Monday, May 31.