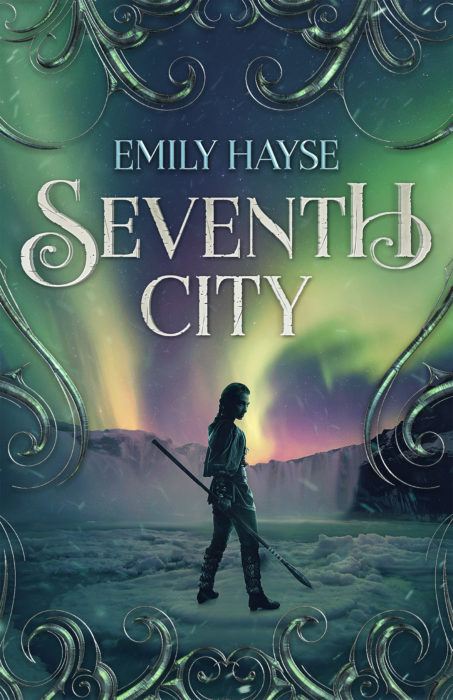

Seventh City, prologue

The last time I saw my mother, she told me a story.

I was five the summer the nomads came to camp near Tansilet. Rangy men, most of them, occasionally with a wife: solemn-faced women with braids, some dark, some fair, but all with that restless, hooded-eyed look that the traveling people wore.

I mistrusted and envied them at the same time. I did not have to be old to know that my own family was unhappy. Especially my mother, since I did not have a father.

One of the nomads came to visit us—a tall fellow with a face that was almost handsome, despite his large chin—and I was tired and restless after he left.

Tsanu was out hunting.

My mother took me on her lap because I was cross. I still remember the sweet smell of her neck and her breath as she spoke. “Little one, why are you so unhappy?”

“I want a story,” I told her.

“Then I shall tell you my favorite.”

I settled in, leaning against her soft shoulder, the skin of her neck cool against my face. The day was warm and I was glad that we were inside, in the shade.

“Long ago, there were six great cities in Uniap’nik, rich with silver and whale oil and nanuk furs, but there were legends told of a seventh, greater than them all—the place where the heroes dwell. It was called Inik Katsuk, and it was closed to all but those who proved themselves worthy.”

“What is it like?” I asked.

She leaned back and closed her eyes as if she could see it.

“Beautiful!”

“How beautiful?”

Her hands, warm and gentle, played in my hair, twisting it into little braids. “As bright as the stars in the sky, as shining as the sun on the stream, as vast as the far mountains. It was a place that all men wished to find, but few did.”

“And the good people live there?”

“Yes.” Her voice was very soft. “The good live there.”

I reached up and touched her face. My mother was beautiful, with her soft skin and dark eyes and full lips. I wanted to look like her when I grew up.

“Someday, I will go to Inik Katsuk,” I declared.

She looked down at me and her face was wistful. I did not know why then, but the memory of it now still hurts deep inside me. “Will you, little one?”

I nodded. Adventures were my favorite thing at that age. “Will you be there, Aaga?” I asked.

Her hand caressed my face. “To be sure, little one.”

I snuggled further into her arms.

“We will go together . . . .”

The sun was warm, and she hummed to me under her breath, and that is the last memory I have of my mother.

I sensed the difference the moment I woke up. The sun was still shining, but I felt the change in the day. It was nearing evening, and I could smell meat cooking.

“Aaga, what is supper?” I remember asking before I came around the side of the hides we had stacked on a basket. “Aaga?”

She was not there. It was my brother Tsanu who knelt in front of the fire, feeding it with sticks to keep the flame strong.

“Maki! You are awake!” He turned and reached out his arms to me in a kind, protective way. I knew immediately that something was wrong.

“Where is Aaga?” I demanded, drawing back from him.

A cloud crossed his proud, twelve-year-old face and he only gestured with his hand. I stood my ground, panic welling up in me. “Where is Aaga?”

His eyes went my face and then dropped to the skins of the two rabbits he had brought back. “She is—gone, Maki.”

“Gone? Where?”

He shrugged. There was finality in his tone, and I knew that wherever she had gone, she was not coming back.

I turned and ran out of the house, shouting for my mother, hoping that if I just ran fast enough, I would catch her. I ran into the camp of nomads, searching around their smoking fires, calling for her, calling and calling her name.

One of the women came over, looking at me with faint concern. “It must be the child of the woman who left with Tassit,” she said, crouching down to look into my face, her long arm draped over her knee. “They say her man was killed by the Invaders on the coast five years ago.”

“Where is my aaga? Have you seen her?” I screamed, panic making me hysterical.

She leaned closer, speaking louder as if that would help. “Do not blame your aaga. It’s a rough life, losing your man, being alone.”

I did not understand her. I only knew that my mother was gone and I had to find her.

“Maki!” It was Tsanu, looking for me. I ran to him.

I remember crying. I do not remember being hysterical, as Tsanu said I was. But I remember his strong arms around me as my tears soaked his shoulder, his smell that of the wild air and pine he had been hunting in all day, his voice vibrating against me as he spoke. “Maki, I am sorry. Maki, I am so, so sorry.” I clung to him tighter, and his arms pressed me closer. “I tried to stop her, I went after her—but—she had to go.”

He peeled me off him and looked me in the eyes. I had to wipe the tears away just to see him.

“Maki, I swear to you that I will not leave you. Do you hear me? And you will not starve.” His voice cracked, but there were no tears.

It was only in hindsight that I realized he was trying not to cry himself.

“We will survive. You and me. Together.”

More from Lorehaven’s fall 2020 cover story

Share your fantastical thoughts.