Roundtable: Engaging That @&*% Our Stories Often Say

E. Stephen Burnett: Welcome to our seasonal Roundtable discussion. We explore dangerous ground at the corner of biblical faith and imaginative fantasy, while striving to follow the apostle Paul’s truth in Galatians, such as Galatians 5:13:

“For you were called to freedom, brothers. Only do not use your freedom as an opportunity for the flesh, but through love serve one another.”

Every panel member professes biblical faith in Jesus Christ. Each friend here also embraces Jesus’s call to holiness. Yet each person also has different views on how we practice holiness in our everyday lives, and in the stories we enjoy as fans.

In our last issue, we explored the topic of fictional violence. Now we move into a theme that is actually even more controversial: the use of “bad” language in fiction.

With Jesus’s help, and with his glory, grace, and truth (John 1:14) in mind, we’ll explore this topic with love and respect for one another. We’ll also try to address specific concerns about story language from fiction fans, parents, and faith leaders.

Laura VanArendonk Baugh loves cosplay and creating speculative stories.LauraVAB.com

@Laura_VAB

Morgan L. Busse has written multiple fantasy novels and mothers four children.

MorganLBusse.com

@MorganLBusse

Mike Duran creates paranormal novels as well as nonfiction about biblical faith.

MikeDuran.com

@MikeDuranAuthor

Steve Rzasa has written multiple fantastical novels and helps run a library.

SteveRzasa.com

@SteveRzasa

First, let’s clarify our definition. By “story language,” we refer to the following:

“Fiction that includes, either in character dialogue or narrative itself, any of these elements: offensive words, crude names, vulgarities, or slang that misuses God’s name(s) or misuses biblical concepts/places.”

(In service to our readers, we’ll try to avoid using these words in print. However, we may post an “uncensored” and longer version of this discussion at Lorehaven.com.)

1. How do you respond to “bad” language in a story?

Steve Rzasa: Most times I can ignore mild profanities. Some of the heftier four-letter words jar me. Sometimes too many [cuss] words interrupt the story’s flow.

I haven’t read a lot of stories that use language insulting ethnicity or sex; I feel those show up less often than other profanity. But those make me squirm, only because our society frowns upon them to a greater degree.

Laura VanArendonk Baugh: I also tend to read “through” most profanity in fiction. I interpret it generally as the characters do, meaning a vulgarity dropped during a space marine bar fight doesn’t shock me, while the dowager duchess’s use of the same word at a season event might make me pause.

A villain’s use of “bad words” can be broader for me than a hero’s, of course. I already know that when a villain says, “Don’t be such a )*##& about it,” that I’m not supposed to like him, and his gendered insult isn’t supposed to be defensible or noble. I’m not keen on gendered or ethnic slurs, but they can sometimes be used by a villain if they fit the story, not just “because.”

Mike Duran: I respond to profanity in fiction the same as I do to profanity in my daily life. Too much of it is tiresome and it’s a sloppy way to converse. But I want to look at a person’s (or character’s) heart and the tone of their life without counting cusswords. So I don’t lose sleep over it.

Add to this the fact that profanity is entirely a cultural (or in the case of Christian fiction, sub-cultural) construct, not a Moral Absolute. There is no inherently evil word on George Carlin’s infamous list of seven words you can’t say on TV.

Absolutely, being around (or reading) profanity can seed your brain and eventually pop out of your mouth. However, proximity to evil is quite different than embracing evil. I mean, if avoiding contact with evil and sin is a prerequisite for holiness, then how in the world can we actually live in the world? Unless, of course, we create our own hermetically sealed culture where “By God’s bones” (and whatever other words we deem foul) is never uttered.

There’s a reason why Jesus was accused of being a drunkard and a glutton. It was the price of loving them. Likewise, we must be willing to tolerate similar accusations for embracing people, stories, and characters that can sometimes be ear-boggling.

Morgan L. Busse: As a fiction fan, I usually avoid most [bad] language-filled books mainly because once I read the words, they’re stuck in my head and I can’t get them out. Then I find myself using such words, and it’s not something I want to say when I’m angry or something I want my kids to imitate.

That goes for anything from cuss words to using God’s name in vain or anything else. It’s a personal preference, but one where I draw the line in the sand quite close to the no-cussing line.

2. What about stories that misuse God’s name or titles?

“Blasphemies and misuses of God’s name irk me more than ‘regular’ swear words.”

— Steve Rzasa

Steve: Blasphemies and misuses of God’s name irk me more than “regular” swear words, because they involve God’s name. That’s why I’ve never used them in my writing, no matter what other words make it in there.

Laura: Bad words with a religious origin is a tougher subject. I live in a world where people frequently use God’s name or its variants as an emotive, and I know what they really mean. However, I also know who they’re talking about. I don’t use any of God’s names inappropriately in my fiction.

ESB: Misuses of God’s name bother me more, and perhaps more so when the genre is mainly intended for children. For example, trailers for Incredibles 2 frequently feature characters misusing God’s name. Disney/Pixar wouldn’t dream of putting scatological vulgarities in the story. And yet these are okay, I suppose.

Mike: What do you mean when you say “misuses of God’s name” by a Disney character? It might be worth noting that God’s name isn’t “God.”

ESB: Indeed. God reveals himself as “Yahweh” and then, of course, in the Person of Christ. Yet I think we should respect any biblical title we use, in human language, to address him. For example, someone could use the name of Jesus as an exclamation having nothing to do with him. “Jesus” is the Greek version of his name. But it’s still, in a sense, his name.

“We have a subconscious human impulse to use even words to reduce sacred things.”

— E. Stephen Burnett

Speaking only about real-life usage here, I’ve wondered if people could substitute, say, the name of a false or nonexistent God (“by Odin’s beard!”). Yet even this seems to betray the fact that we have a subconscious human impulse to use even our words to reduce sacred things. At the very best, it’s meaningless language. Which we do hear in real life, of course, and therefore we could arguably also “hear” in fiction. I just doubt very much we will ever hear this language in eternity.

3. What about language in books versus film or TV?

Morgan: Either way, I don’t find it surprising and I’m not shocked. I grew up around cussing. (Most of my family is not Christian, my dad was a sailor in the navy, and both of my grandmothers cussed—one in Norwegian.) Since personally I don’t want to use those same words, I choose to limit my exposure to them in media. But I’m not shocked or horrified by their usage. Perhaps a little sad, but why would a person not use God’s name in vain if they don’t personally know and follow him?

Mike: I doubt I respond differently, but the science probably says the audio-visual is more viscerally impacting. But with either occurrence, written or spoken, we must exercise the same vigilance and discipline.

Steve: I agree, Mike. Though interestingly, the written overuse of profanity bothers me more. Perhaps that’s because growing up, and even through my early adult years, books I read had fewer swear words than movies I watched. They certainly had fewer than my friends and I used in high school, us being heathens and all.

It intrigues me that everyone has varying thresholds, even (perhaps especially) among Christians. I’ll say this: seeing the Lord’s name in vain on paper bothers me more than hearing it, because in audio form, I wince and it’s gone. On paper or the screen, it lingers, even after I’ve moved on, and my brain says, “Hey, remember what he/she wrote on page 45? Yeah, me, too.”

Laura: I don’t know that I have any strong opinions on hearing versus reading. I don’t particularly like either, but for me personally I don’t think one venue strikes me harder than another. I do believe other people who say they experience a difference, though. Bring on the controversy!

4. How may Christians respond to story language?

Laura: I see two general categories of response.

First, there’s the invisible response, in which the Christian reader reads over the offending word, may or may not react internally, but doesn’t advertise.

Second, there’s the offended/moral outrage response, in which the Christian reader advertises widely that he read a word but was really upset about it.

“Sometimes the adrenaline high and self-congratulation of moral outrage can replace actual discernment.”

— Laura VanArendonk Baugh

There’s definitely a place for quoting offensive content. If I am protesting something moral or ideological, I need to be specific and accurate. But if the protest is “this makes me feel dirty,” then I should probably move away from it. Sometimes the adrenaline high and self-congratulation of moral outrage can replace actual discernment. Did that middle-school-boy-style dialogue lead to sin? Or was it just not what she liked? Did she avoid sin by posting her detailed complaints? Did other readers avoid sin by reading them? Did I avoid sin by reading them?

Mike: Personally, I don’t bother much about how other Christians tend to respond to story language. This doesn’t mean that I’m insensitive toward concerns. Instead, I’ve hung in Christian reader circles enough to know the general objections to profanity and don’t feel obligated to acquiesce. There’s several reasons for this.

First, I don’t write for the Christian market. If I did, then I would adhere to the stricter language guidelines.

Second, much of the objections to profanity in film and literature I find non-compelling. Those objections typically come back to matters of personal preference rather than clear-cut biblical restrictions.

Finally, creatives need to stay true to their stories. In other words, if a story demands the inclusion of [“bad”] language, then we should honor the story. The moment a storyteller or artist fears including something controversial because of how a reader or viewer might respond, we sublimate our creative freedom for another’s self-imposed boundaries.

Morgan: In the end, this response is between the reader and God.

Some people are too sensitive and have a superior moral complex. But some people have legitimate concerns, maybe because of their background, which causes them to be more sensitive to language. For example, I have a family member who wants to change the words they use because now they are a Christian and that kind of language reminds them of their former life. I get that.

But on the other side of the pendulum, there are verses cautioning us on how we speak. Are we edifying those who are hearing us? Is it an appropriate word for the moment? It depends on the situation, the culture, and again, between the reader and God.

Steve: Some individuals take an author task for including an swear words—even ones that are considered very mild for use in the past thirty to forty years—as if writing the words coming from an imaginary person’s mouth makes the author a bad Christian. It isn’t that such critics come out and say it, but this attitude is there: “if you were a better Christian, you wouldn’t use those words.”

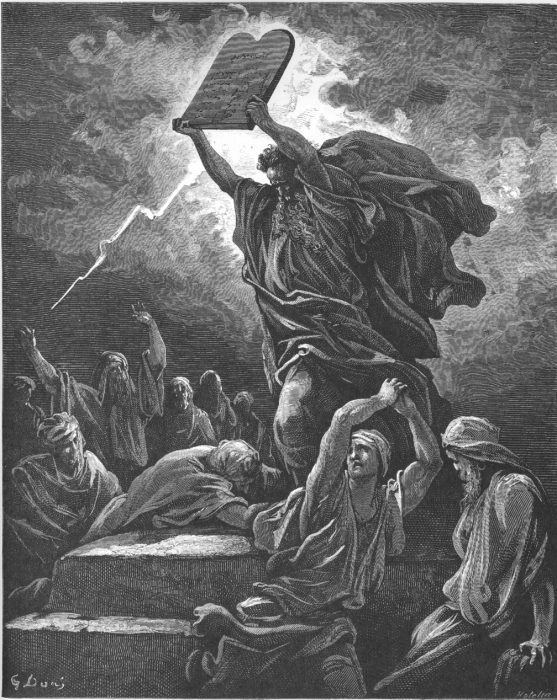

God’s third commandment to Israel states, “You shall not take the name of the LORD your God in vain, for the LORD will not hold him guiltless who takes his name in vain” (Exodus 20:7, ESV). (Image from Gustave Doré’s 1866 painting Moses Breaks the Tables of the Law, public domain.)

4. What are the best arguments against story language?

ESB: For example, some Christians seem to assume that if you read (or hear) a bad word in fiction, then you will inevitably tend to use this word, in a sinful way, in real life. I’ll confess: there is some truth to this, at least for me. Looking back, I kept my own language fairly “clean”—until about the time I started watching comedy YouTube videos starring intentionally foul-mouthed hosts. The difference is this: They’re using these words to be funny (whether this is acceptable is another issue). But I tend to use these words when I’m angry (which is a sin!).

Laura: Obviously if something is affecting you, you take steps. If I watch a lot of film noir and I find myself wanting to smoke, I need to come up with an alternate behavior for myself. If I play a lot of Assassin’s Creed and I start feeling myself tempted to parkour over a railing and down an atrium, I need to resist. (I resisted.) If I watch or read a lot of language and start using it in a way that’s offensive to others and/or myself, I need to examine that and make a call.

Morgan: Some Christians are truly concerned about certain language used in fiction. Either they have not thought through their convictions and know where their own line is, or as Laura pointed out, they have double standards (which need to be addressed). However, there are times when the language serves no purpose in the story. And let’s be honest, there is an assumption out there concerning Christian fiction that there won’t be any bad language, or if there is, there is a really good reason.

Steve: Christian publishers can rightly make the case that, if they’ve built a business on books that don’t contain profanity, they shouldn’t put it in. They’re more likely to drive off some readers for those same reasons we’ve articulated, whether or not we agree with those reasons. I don’t think adding profanity to a explicitly Christian line-up will attract new readers. Different stories will do a better job at that than the language used in those stories.

“Separation from the world is a spiritual state, not a literal checklist.”

—Mike Duran

Mike: There is no disputing that reading and/or hearing profanity can negatively seed our imagination. Listening to people cuss tempts us to cuss. Bottom line. Full-stop. Here’s the problem, as I see it: Any contact with a fallen world can tempt us to sin. Living around people with unhealthy lifestyles, values, and habits can influence us to mimic those things. However, as Christians, we can’t isolate ourselves from sinners because they might tempt us to sin. In other words, it’s wiser for us to cultivate discipline in resisting evil than it is closing our eyes and ears to every possible form of evil we encounter. Separation from the world is a spiritual state, not a literal checklist.

5. How do we respond to Christians with different views?

ESB: For example, let’s say we want to recommend a book to someone that has some bad language in it. Do we be proactive and caution that person? If so, is there any way, as Christian fans, for us to do this on a widespread scale? What about fans of different age[s] or maturity levels? How does this affect the issue?

Laura: Recommending books (or other media) to professing Christians is a lot harder than it should be. For example, I remember the first time a lent book was returned to me with, “I don’t read books that take God’s name in vain.” I had honestly not remembered the book had this in the dialogue. But I do remember the feeling of bewilderment. Thus, I generally find it easiest to simply not recommend books or movies to people I have heard complain about content issues, including language. No problem, find your own.

Morgan: Engage in conversation. Find out why they have different views or needs. Perhaps they [are] more conservative and that’s okay; we all have lines we don’t cross. Perhaps they have kids and they want to know ahead of time [about bad] language, so either they can choose not to have their kids watch the show or watch it with them and dialogue about it.

Mike: When speaking to other believers, I’ve gotten into the habit of simply qualifying my stories as being PG-13 level, sometimes containing horror elements, and not fitting tightly into a Christian fiction framework. This is typically enough info to allow readers to make up their own minds.

Steve: I make sure to discuss matters of language when I talk with folks. Sometimes it’s a matter of getting a read on them. If their preferences tend to secular books, I can figure that profanity mostly doesn’t bother them. Sometimes, when we’re talking about their kids, the topic of swear words is front and center. It does come down to knowing the reader and being willing to have a discussion on the matter.

6. How does story language affect real language?

ESB: As we’re exposed to certain language—either from the people around us, or from the stories we explore—how can we, as Christian fans, continue to pursue holiness? How can we glorify our Savior while not being affected by temptations to use anything, including certain words or phrases, as expressions of sin?

Laura: Despite all my “liberalist” ranting, I am actually pretty conservative about showing stuff to kids, more than a lot of parents. I’ve challenged inclusions in the kids’ section at bookstores, even though it was a title I myself really enjoyed. Parents and responsible adults need to be very cognizant of what kids take in, and I don’t believe there’s a universal guide for that. Like personal responsibility, it needs to be matched to the reader/viewer.

I have often stepped aside with a parent to show them key pages in my books before either closing a sale or suggesting another book to the kid browsing at my table. I’ve lost sales this way, but I’m still going to eat and it’s the right thing to do.

“It’s about each person knowing their limits and placing those before God.”

—Morgan Busse

Morgan: It depends on each person. I can struggle with language if I’m around it a lot, but my son has no problem. It’s about each person knowing their limits and placing those before God.

Mike: This likely comes down to individuals. While I don’t think it can be denied that “bad communications corrupt good manners,” we must also acknowledge that we’re called to interact with sinners in a fallen world without having to wear blinders and earmuffs. Reading or hearing profanity can undoubtedly make its way into our own thoughts and speech. But living in a fallen world, in general, can result in the same thing. In the same way that we must remain separate from the world while living in it, we must navigate how to interact with sinners without adopting their habits and values thoughtlessly.

Steve: I am one of those people who absorbs language around me, so I have to be on my toes. I agree with Morgan’s commentary on the matter, but also echo Mike. We as Christians can’t do the earmuff thing if we want to engage with others.

Share your fantastical thoughts.