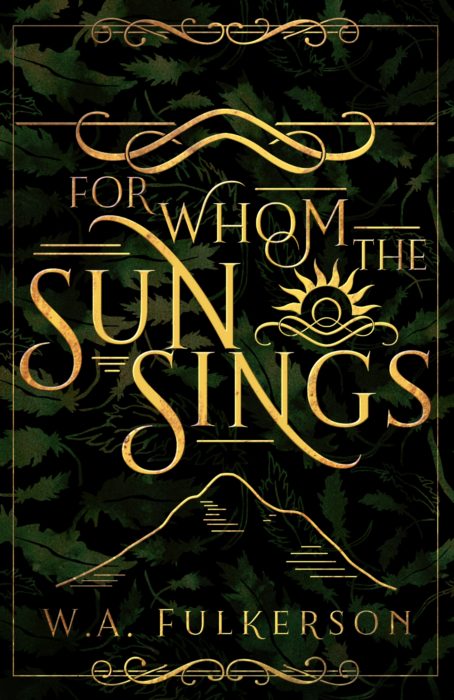

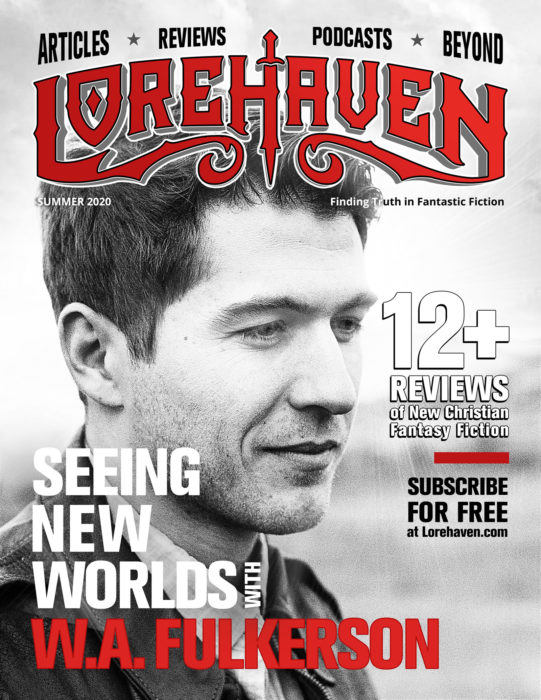

‘I Used to Want to Change the World’

Explore For Whom the Sun Sings with novelist W. A. Fulkerson

What images and ideas helped make this story?

There’s an old saying: “In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king.” It’s one of those phrases that we hear and don’t often question. A few years ago, however, I started ruminating on this adage and it got me to wondering, “What on earth is the land of the blind? Where is it, and what is it like?” That was the seed that grew into For Whom the Sun Sings.

How did you become a Christian who creates stories?

I became a Christian as a child, thanks to my parents teaching me young, and I’ve been telling stories in one form or another for as long as I can remember. I think in stories, I dream stories, and when I drift off into thoughts, it’s scenes and dialogue. It’s how I’m built. During my time at the University of Southern California, I felt a calling to go into the arts as a profession, and I’ve been writing ever since.

What can Christians uniquely bring to fantasy-crafting?

This question is so important, very interesting, and the answer probably somewhat different than you might expect: The answer is absolutely nothing.

Or do we forget what God says in Isaiah 45 when he selects Cyrus the Great (who was not a Jew or believer) to be his chosen instrument? God says, “I name you, though you do not know Me. . . . I equip you, though you do not know Me. . . . I make well-being and create calamity; I am the Lord who does all these things” (Isaiah 45:4, 5, and 7).

God is sovereign, and he is able to inspire you, me, or a pagan to write the works that will accomplish his purposes. This should humble us and spur us on to pursuing mastery of our craft, whether you are a writer, a contractor, an accountant, or anything else. We can do this with all excellence to the glory of God, knowing that he is not obligated to use me over another.

What do you feel is your purpose in writing stories?

I used to want to change the world. I thought that if I studied hard enough, practiced endlessly, and produced at a great rate, I could play a role in shifting the way we think—influencing the culture to a more Christ-centered understanding and worldview.

Now, there’s something in that idea that is good and something that is perhaps immature. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to realize that God allows us to partner with him in his work, but the work is still dependent on him. I can (hopefully) present information artfully, but only the Spirit is going to change someone’s heart or mind.

So, I see my purpose now as loving the craft because God himself seems to love stories, and in what I write I strive to illuminate truth and beauty. Whatever happens from there is out of my hands.

What’s next for you?

A lot of novels I’m not at liberty to discuss just yet, at various stages of completion. People typically have a to-be-read list. I have a “to be-written” list that’s getting longer all the time. I’m also hopeful that I’ll get the opportunity to adapt some of my work for film or television someday.

For Whom the Sun Sings, featured review

For Whom the Sun Sings, featured review

W. A. Fulkerson’s debut opens the eyes of adults with childlike faith.

In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king. Or so the proverb goes. He might also be a freak, especially if, in the blind land, no one knows what sight is. Then when the man sees the truth, and makes himself its guide, he will be a menace.

W. A. Fulkerson constructs For Whom the Sun Sings on an ingenious premise. He carefully builds a society without sight, working out the idea to consequences both obvious and unexpected.

For example, characters throw out words like snow and blizzard as oaths, and it is easy to dismiss as the sort of swearing an author writes when he doesn’t want to write real swearing. But if you think that, you will think again. When the story vividly brings home how easily the blind are lost, and lost fatally, in a sudden snowstorm, blizzard as a swear word becomes a clever bit of world-building.

Other small touches complete the reality of a world without sight. Fulkerson does not neglect the larger implications of his premise, but the details bring it home.

The novel appears at first to be pitched to a middle-grade audience, with its eleven-year-old protagonist and its skillful but not elaborate style. Then, brief and strong content pushes the novel toward older readers. Two violent episodes are neither extended nor unduly graphic, but are still skin-crawling. In addition, an authority figure “marries” a thirteen-year-old girl—an action that, with one exception, meets with nothing but approval and complacency. This disturbing complaisance realistically reveals the world in which the story occurs. The author trusts his readers to understand the horror without preaching, and to trust him that he understands it, too. But that is a trust for adults.

Other elements are beyond children. The misshapen nature of this small society, slowly elaborated over the course of the story, is best understood by adults. Once they see its core, they will recognize the society of the blind. Its spiritual family haunts the history of the twentieth century. Grown-up content is for a grown-up audience, and an eleven-year-old hero is an obstacle to that. Yet a very young protagonist is necessary to the author’s purpose. The hero’s journey in this novel leads to discovery of the very concepts of see and blind, and slow realization of the falseness that cocoons their lives. This would scarcely have been justifiable in an adult.

There is an obvious religious metaphor in the one seeing person in a society of people who do not know that they are blind. Sometimes the novel openly plays to it, even alluding to Christ’s maxim about the blind leading the blind. Still, the metaphor flows naturally from the story. Religion in a corrupted form is central to the novel, with a society headed by the Prophet and colored with a cultish tinge. True religion is little more than suggested, but is unmistakably suggested.

Subtly at first, and more emphatically as it progresses, this novel is divided between two audiences. One would be reluctant to recommend it to parents, except, perhaps, for themselves. For these readers, For Whom the Sun Sings is a creative tale of unexpected depth.

Best for: Fans of dystopia and The Wingfeather Saga.

Discern: A brutal murder, a cult-like leader mutilates himself and tells others to follow him, adult/teen marriage, domestic violence, child abuse and abandonment.

For Whom the Sun Sings, chapter 1

Andrius started the day like he started every other day: he opened his eyes.

It was still early and his song rang freshly inside his head. He remained under the woolen covers a moment and whispered the lyrics to himself.

“Who can make a world for us?

Zydrunas, Zydrunas

The strongest heart he turned to dust,

Zydrunas, Zydrunas

He made a place for us to be

Fought back the disease—”

Andrius stopped. That part didn’t rhyme exactly, and the rhythm wasn’t too good either. It hadn’t stuck out to him when he was making it up yesterday, but now it sounded wrong. He would have to fix it before he arrived at lessons. Andrius wasn’t very good at music. It seemed like he was the only one who struggled with it.

Take-home assignments were not his strong suit.

Andrius snuggled deeper into the warm, scratchy blankets. It was hard to hear this early in the day because the sun wasn’t singing yet. The cows, however, were singing. They lowed softly from across the barn, asking to be milked. He hoped Daiva wouldn’t hear them from the house.

“Andrius!” a husky voice called out, making him wince. “Are you deaf?”

He was out of the covers in an instant, trying not to topple the pile of hay that made up his bed.

“The cows need to be milked and you’re sleeping in,” the same voice shrilled. “Lazy cad!”

Of course she had heard the cows lowing. Father said that Daiva had ears as sharp as her tongue. Of course, even as Daiva chastised Andrius for lying in bed, he knew that doubtlessly she was doing the same, but Andrius didn’t think about that. Instead, blinking sleep from his eyes, he walked to the milking pail and took it in his hands. He took a sip of water from his wooden pitcher, then he picked up the milking stool and made his way to the cows.

Teats felt uncomfortable in his hands. He hated milking. He hoped the sun would sing soon so that he could at least hear.

.^.

“Andrius? Is that you?”

Andrius smiled as he entered the house, looking for something to eat. There was a plate on the table with five boiled eggs and a pile of bacon on top of a bowl of swelled grain.

“Yes, Father.”

“Have you finished your chores?”

Andrius reached into his pockets and delicately placed each egg he withdrew into the basket hanging on the wall. The chickens were laying well recently. Spring was good for eggs.

“Yes, Father.”

“Good, good. You’re a good boy, Andrius.”

His father took a bite of one of the eggs on his own plate, which was more reasonably portioned: two eggs, one piece of bacon, and a spoonful of grain. He was a thin man and his wispy hair betrayed his age.

Andrius kissed his whiskery cheek and sat down next to him, stomach growling.

Suddenly the door slammed and Andrius jolted, dropping a piece of bacon.

“Andrius!”

The shrill sound took the slouch right out of him. He turned his head toward Daiva.

“Hello, dear,” his father greeted her gently.

“Aleksandras, is your name Andrius? Am I speaking to you?”

“No, dear.”

“Then keep your ‘dears’ to yourself.” Daiva slammed a meaty hand on the table and slid it to the teeming plates in front of Andrius. She pushed them away. “How many eggs did you collect today, Andrius?”

“Seven.”

“Liar.”

“You can check. They’re in the basket.”

Daiva frowned, then lumbered her way over to the wall. She had ratty hair that she rarely bothered to brush and speckles on her arms just like the eggs. She was much younger than her husband, but that did not make her pleasant. She had a quick temper and she never let anyone touch her. Hugs were out of the question, not that Andrius particularly wanted to hug her.

“And I know you aren’t sitting in my seat,” she said as she touched the fresh eggs in the basket, counting them.

There were only two stools, so of course he was in her seat. He stood up.

“Let the boy have a seat,” Aleksandras said. “He’s been on his feet all morning.”

“And I haven’t?” Daiva challenged as she counted the freshly collected eggs once more. “Certainly, put the boy in a seat but let your darling wife who slaves away all day long stand on her feet. Yes, I understand your point, Aleksandras.”

His father leaned over. “You better stand up, Andrius,” he said in an undertone. Andrius was standing already.

The floor shook as Daiva lumbered over to the table, felt for her seat, then collapsed into it. She was breathing from her mouth like she usually did. Andrius wasn’t overly fond of the noise, but he stayed quiet. Daiva reached forward and pulled the mountain of eggs, bacon, and grain toward her and she began to eat.

She was a loud chewer, not bothering to close her mouth much of the time. Andrius’s stomach grumbled.

“Are you still standing there?” Daiva asked halfway through her fourth egg. “Go to your lessons.”

“I haven’t had any breakfast yet.”

“You’re doing a poor job with the chickens.”

“But you just counted the eggs! There were seven this morning and six yesterday.”

“You’re flustering them when you collect. That will make them lay less often, so I’m making up for it by saving eggs this morning. Now go to your lessons.”

Andrius’s shoulders slumped. This was so unfair. He grumbled inwardly along with his stomach as he picked up his water pitcher and walked out the door.

He muttered to himself once he was far enough away that no one would hear him. “I need to eat something.”

The door clamored shut and he turned around. His father was approaching, bumbling along as fast as he was able.

“Andrius!” he called. “Andrius, wait a moment!”

The old man caught up to him and let go of the rope that led from the main road to where they lived on Twenty-fifth Stone.

“Andrius,” he said again.

“Yes, Father?”

Aleksandras held out a hand with two long, narrow sticks.

“You forgot your cane.”

“Thanks, Papa.”

Andrius took the walking stick and Aleksandras tussled his hair.

“Did you finish your song for your lessons today?”

“Not yet. I have something but it isn’t right. I’ll finish it as I walk.”

His father, bent over, nodded in agreement.

“Yes, yes you will. You’re a smart boy. You’ll figure it out.” He smiled. “How are your magic ears? Ready for tonight?”

Andrius stood his four-and-a-half-foot body a little straighter.

“They’re sharp as ever.”

“Herkus says he has a set of stones so smooth he’ll finally crack your winning streak.

“The only thing he will hear crack is his heart when he realizes how much he has lost to us.”

They laughed together then. The sun was now singing loudly overhead. He could feel its rays on his skin.

“That’s my Andrius. You’re a smart boy. Do well at lessons. You’re always forgetting your cane.”

Andrius held the stick in front of his face. He didn’t know what the big deal was.

Aleksandras lowered his voice and reached into his pocket.

“Also,” he said, “you forgot this.” A beautiful boiled egg appeared in Aleksandras’s hand, wrapped in cloth. Andrius practically leaped for joy. He took the food and kissed Aleksandras on his whiskered cheek.

“Thank you, Papa.”

“Shh,” Aleksandras whispered. He tilted his head up to listen for a moment. Hearing nothing, he patted Andrius on the shoulder. “Enjoy your lessons,” he said louder. He chuckled to himself. “Is that your water pitcher sloshing around? Why do you always carry it with you?”

“I get thirsty a lot. Thanks, Father.”

Aleksandras grunted in assent and made his way back to the house holding onto the rope with one hand and his cane with the other.

Andrius took a bite out of the warm egg and sighed in satisfaction. He skipped every few steps as he went on his way along Stone Road.

Reprinted with permission from W. A. Fulkerson and Enclave Publishing

Share your fantastical thoughts.