Try These Three Practical Questions to Discern Fictional Magic

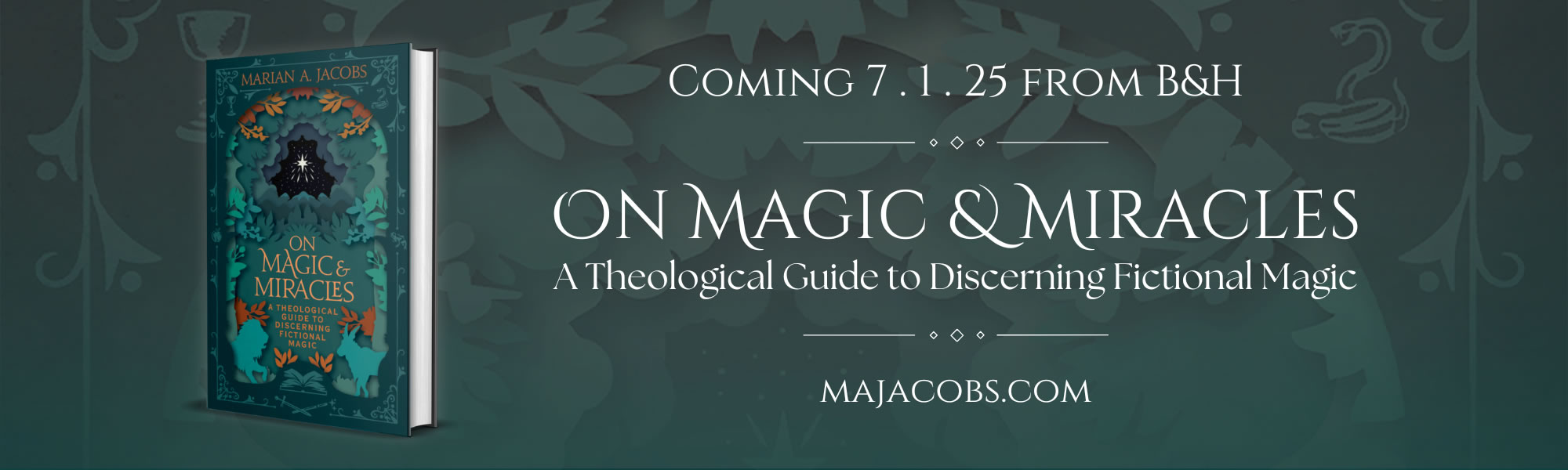

Since modern fiction has collapsed the categories of “magic” and “miracles,” we must use biblical truth to discern good and bad magic as well as other supernatural powers in films and books.

In my article “How Do We Discern Good and Bad ‘Magic,’” I urged fantasy readers to look closely at fictional magic through a biblical lens.1 In this article, we’ll apply those ideas to readers and parents who desire to think biblically and critically about the stories they or their children explore. Below, I’ve provided three questions to consider.

Question 1: What is the source of the magic?

Many stories may answer: one’s self, a higher power that isn’t God, or God himself.

First, if the source of the magic or supernatural power source is one’s self—the magical power user—this could show the story’s worldview is self-focus.

Frozen II specifically depicts this source in the song “Show Yourself.” Although the story doesn’t reveal the origin of its elemental “spirits,” we do see that Elsa’s deceased mother called her so Elsa can take her place as the fifth spirit within the magic system. The song is somewhat vague, but implies that it isn’t her mother that Elsa’s been searching for all her life, but herself.

Second, a story’s magic source could be a higher power that isn’t God.

Star Wars offers a good example with the Force. This power source shouldn’t be seen as a magic system but a natural-law power in the universe. For example, the Midi-chlorians, sentient cells within a person, allow someone to detect the Force (which is either non-sentient or simply impersonal) because it is the higher power. Only with these cells can people wield the power of the Force for their own purposes.

In the real world, demonic powers are an example of a higher power that isn’t God.2

Third, some fantasy tales ascribe supernatural power to God.

Although most modern stories will not mention God by name but assign him a new name that fits within their fictional universe. For example, Nadine Brandes’s young-adult historical fantasy novel Fawkes shows White Light as the sentient, personal, and loving source of all magic within that world. This option most clearly reflects a biblical worldview.

Question 2: Does the magic system naturally produce good, bad, or neutral results (or does the result depend on the user)?

Stories may show magic as neutral tools, naturally evil, or naturally good.

First, most fictional magic systems are neutral tools, used for good or evil.

The magic in the Harry Potter series is a good example of this. For the most part, the magic itself doesn’t have good or bad intent and can be used for good or evil depending on the spell caster’s intent. The Wizarding World’s only exception is dark magic that can only produce evil results at a very high price (such as creating a Horcrux or killing and drinking unicorn blood). When using dark magic, the spell casters’ intent doesn’t matter since the mere use of dark spells implies they have ill intent.

Harry Potter is far from a perfect magic system when comparing it to the Bible, since the origin of the magic is not God. Still, this option of “magic as a tool” can actually align with Scripture when done well. This may surprise you, but the Bible gives many examples of God’s people using God-given supernatural power with questionable motives for their own ends. (See Judges 15:14–15, Numbers 20:9–13, Matthew 7:22–23.) Still, when this happens in Scripture, it doesn’t fall outside the Creator’s plan. It’s ordained to demonstrate God’s power and glory in using weak, disobedient people for his purposes.

Second, fictional magic systems can be naturally evil.

Marissa Meyer’s series The Lunar Chronicles portrays this evil magic through the Lunar gift. The Lunar people have the ability to command others’ thoughts and actions, stripping them of their wills and even consciences until they are “released” by the controlling Lunar. Some Lunars attempt to use this power for good, but their “gift” is still naturally evil and seen as a burden to the heroes.

Third, some magic systems are naturally good and cannot be used for evil.

Barbie and the Magic of Pegasus provides a good example of this. (Yes, I let my daughters watch Barbie movies.) With a vengeful and angry heart, Princess Annika attempts to use her magic scepter against the villain. But nothing happens. The magic fails because Annika is not acting in love or to save the lives of others.

This option can reflect hints of a biblical worldview. But these things are not static in the Bible because our true source of “magic” is a thinking and planning God, who gives and takes away when he sees fit. Sometimes he may restrict the use of “magic” if our heart is in the wrong place, and sometimes he may not. In fact, only the second option—naturally evil magic—always conflicts with a biblical worldview.

Question 3: What are the hero’s motives while using the magic/power?

We’ve explored the intent of magic users, focusing on how their motives affected the magic’s outcome. But if a story’s magic system is not affected by the user’s motives, we still need to look at the hero’s motives apart from the magic. This question has more to do with discerning if the magic users’ intent fits within a biblical framework?

This is more complicated than simply answering, “Yes, the heroes have godly motives,” or “No, they don’t.” The difficulty isn’t discovering their motives (often that’s the easiest part). Instead we must ask whether the heroes’ motives are appropriate for this point in their character arc. If they have poor motives in the beginning or middle of their journey toward becoming a better person, that isn’t necessarily bad. In fact, we need to see an imperfect hero behaving badly at the journey’s beginning so we can see them grow and change later on.

For example, Frozen’s iconic song “Let It Go” drew flack from some Christians who critiqued the song’s self-centered relativism with lyrics like, “No right, no wrong, no rules for me.” It’s too bad this was the catchiest song in the entire film, Elsa near the start of her character arc during this scene. She flees to her magicked ice palace in the mountains because she’s afraid and overwhelmed by her parents’ over-the-top restrictions. Elsa is not in a healthy place. Later in the film, we see this revealed when she comes home and melts her winter with selfless love.

Epilogue

Christians need to move beyond simply accepting or rejecting all fictional magic in films and books. The Bible offers a wide array of narratives providing us clear examples of how God has chosen to order his creation. As you read the Scripture, ask yourself how God has invited mankind into his beautiful world of magic and miracles.

- For a deeper look at those stories, see the above article as well as “The Biblical Source of Super-Strength.” ↩

- I use the term higher loosely. Demons are only “higher” than humans in the sense that they possess powers we don’t. See Mark 5:1–20. ↩

Honestly, I find question 3 to be the only one that is actually interesting. Especially the contrast of characters doing the wrong thing for entirely sympathetic, or even good, reasons. Mmm yes, dat psychology.

Because Elsa is sympathetic because her neutral magic had always been treated as naturally evil. Or take your classic DnD alignments, where Lawful can also be Evil, and Chaotic can also be Good. That last one, especially. Because many anxious and insecure types do their copes with rules, so they are inclined to take disruption as inherently bad, even if it isn’t. Is it Evil, or is it merely unorderly? (PS, that pretty much sums up my take on the Question of the Gays. You can probably guess where I land.)

I personally wouldn’t conflate something like the Midi-chlorians as “a higher power other than God.” As you said, they’re a “natural-law power in the universe.” This, to me, is its own category. Anything natural to the world is inherently set in place by the creator of that world, whether that fact is acknowledged or not; therefore, personally, I’d categorize it more closely under “attributing supernatural power to God,” even if it’s not explicitly stated as such.

Depending on the degree of self-centeredness, I’d even place many “self”-powered magic systems in this category. I definitely understand drawing a distinction in cases like Frozen II where it’s very much emphasized that all the character needs is themselves; that’s a humanist viewpoint that should be acknowledged. But in cases where magic is, say, a genetic element, it is also built into the world as the creator made it.

I would concede that lines get fuzzier as you look at media with varying degrees of secular vs. theistic thought. The more the worldview of a given piece of art reflects secular humanism, the less wiggle room there often is to acknowledge a potential in-world creator influence (like when you look at Frozen II).

This is a great article, and I appreciate the food for thought! There are several angles or issues to consider with fictional magic, and these are good ones to start with. 🙂