How Political Punditry Has Taken Over Christian Popular Subcultures

Not even the weirdest trends of yesteryear have dominated Christians in America like the latest, greatest trend: politics.

These days, U.S. Christians love them some politics. Political discussions, debates, speculations, and even conspiracy theories are totalizing and inevitable.

Here, I don’t plan to repeat the same debates, though I’m not above doing so elsewhere.

Instead, let’s ask a bigger question: How did Christians, at least those in the U.S. and similar contexts, get here?

Politics have taken over Christian trends since 2016. But their roots go far deeper than that. My own awareness of Christian trends begins in the late 1990s. That’s when I discovered this thing I called “Christian popular subculture”1 as a fan, from the inside.

Ever since then, I’ve tracked our trends in the 2000s and now 2010s. Yet thanks to some background reading, including old Moody Monthly magazines lying about the Burnett homestead basement, I also have some idea of the 1980s and early ‘90s.

Based on this familiarity, I can identify this correlation: Starting in the early 2000s, after the failure of various end-times expectations and the start of Sept. 11–related terrorism fears, Christian popular subculture began to change. We went through our leftover bins. We tossed out our old trends. Instead we bought us some double-truckloads of politics: talk radio, websites, ministries, groups—the right-wing works.

Nothing since then has been the same. No matter how you view America’s political situation now—it’s bad, but we disagree on reasons—the change hasn’t helped us. Yet a few early signs show that we may be ready to re-broaden our subcultures.

Looking back on previous Christian popular subculture trends

My casual research and memory reveals a few Christian popular subculture oddities over the decades. Overall I would class these as mixed-positive in effect:

- 1970s: We had the Jesus Movement, and early Christian rock and folk music. Also, early end-times speculation spread, thanks to Hal Lindsey’s 1970 book The Late Great Planet Earth.

- 1980s: Evangelicals on TV begin the rise of prosperity preachers and faith healing. Many Christian groups (like Focus on the Family) start creating more

popular subculture, with shows like “McGee and Me!” VHSs and “Adventures in Odyssey” audio. Cassettes spread praise music. Christian bands begin experimenting with music styles, with performers like Amy Grant and Michael W. Smith leading the booming scene. Christian bookstores grow. In the end-times world, Cold War–fueled speculation continued, thanks to more books from Lindsey and others, leading to one or two failed Rapture predictions.

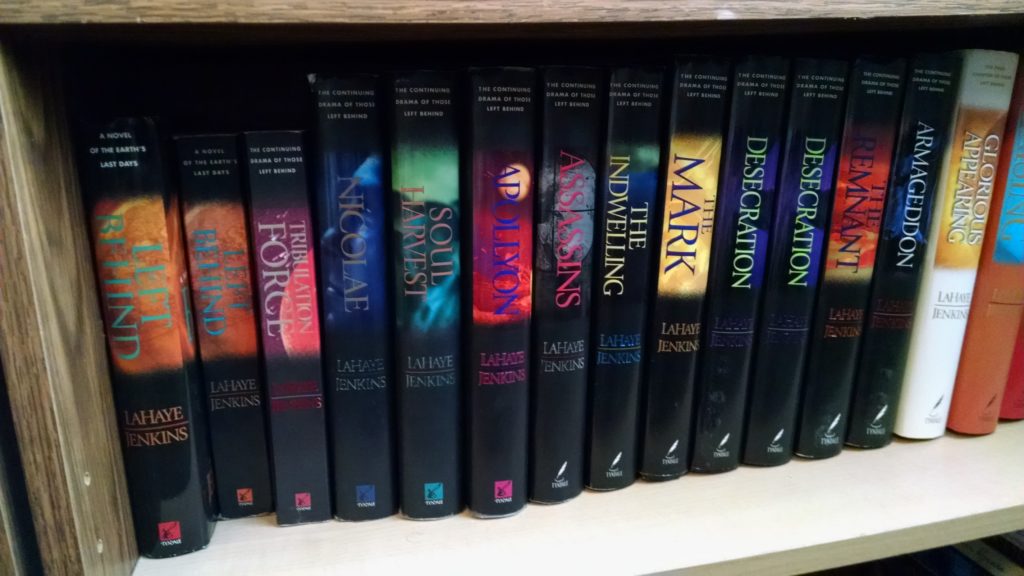

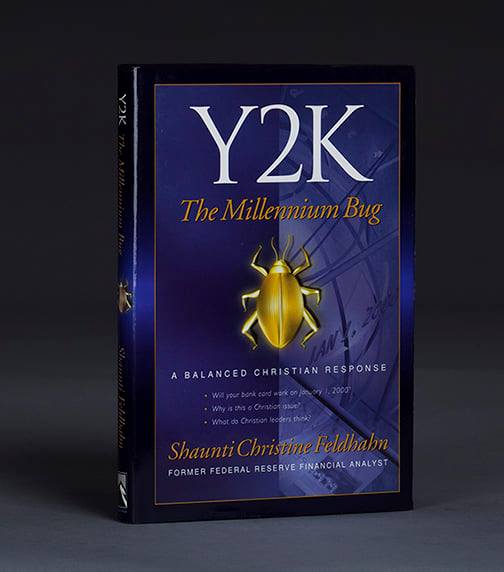

popular subculture, with shows like “McGee and Me!” VHSs and “Adventures in Odyssey” audio. Cassettes spread praise music. Christian bands begin experimenting with music styles, with performers like Amy Grant and Michael W. Smith leading the booming scene. Christian bookstores grow. In the end-times world, Cold War–fueled speculation continued, thanks to more books from Lindsey and others, leading to one or two failed Rapture predictions. - 1990s: Angels flew everywhere (early ‘90s). Contemporary Christian music becomes a new thang, led by some artists who seem to “borrow” liberally from “secular music,” but others who, in retrospect, truly forged new frontiers in musical and spiritual creativity. VeggieTales bounces happily into Sunday school classrooms and explodes into a massive fandom that is likely still unequaled by other evangelical fads. In this decade, end-times speculation turns into arguable all-out mania, including but not limited to the Left Behind series as well as the Bible Code–related silliness (both in the late ‘90s). “Y2K millennium bug” fears spark panic (late ‘90s, ending right on Dec. 31, 1999).

-

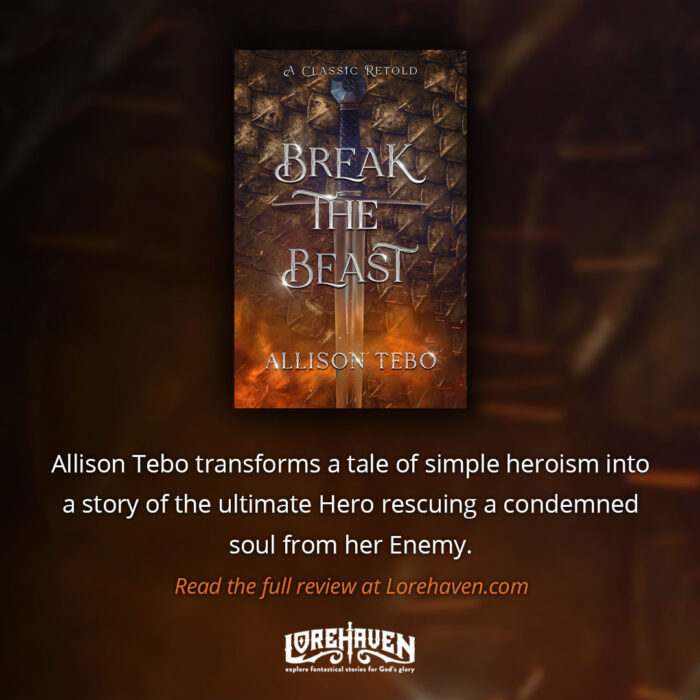

Photo from Kirk Douponce, who actually designed the 1999 book’s cover.

2000s: Wild at Heart and related resources spread “we need us some more men around these parts” movements (early 2000s). The Prayer of Jabez drew other “we need to have big faith” movements (also early 2000s). Sept. 11 began terrorism fears and Islam apologetics as well as more debates about politics, foreign policy, and war ethics. “Young, Restless, and Reformed”2 churches and groups boom, aided by proliferating blogs and later, podcasts. The Left Behind series fandom concludes.3 Da Vinci Code–related apologetics flares and ends.

- 2010s: Some trends follow, like Christian adult coloring books, the Jesus Calling devotional and spinoff products empire. We also see many Christian movies, from creators like the Kendrick Brothers and PureFlix, which made films for thousands that made millions. But mostly, it’s politics politics politics.

When did politics start taking over Christian popular subcultures?

Looking back on this admittedly very generalized list, I think I’ve found the point that politics took over. It’s there with the only specific date I included: Sept. 11, 2001.

At that point, Christians’ moods in America had begun to shift. Naturally the first day of the year 2000 sent all our many hardback “prepare for the Y2K bug” books to the desperately-bargain bin. Quite a few sheepish shepherds quietly began rolling back their “this is how the Antichrist takes over the world” speculations. Some end-times trends, however, forged onward, including but not limited to the Left Behind series, whose authors wisely avoided attaching themselves directly to the “Y2K” trend.4

By December 2000, however, the mainstream-liberal Clinton administration was waning and the conservative George W. Bush administration was on the way.

This caused some evangelical Christians, at least subconsciously, to re-think their assumptions about the end actually being near. Hey, many of us thought, starting to look warily at our Tim LaHaye prophecy timelines. Maybe we still have some decades.

Then Sept. 11 hit, and we bolted for those timelines all over again. Out with the old theories (first the Soviets, second the computers crashing and the Beast moving in to give us all microchips). In with the new theory: terrorists! This concern was very real, for sure, but also overblown by many well-meaning Christians. It brought to evangelical minds all manner of “holy war” memes and histories and apologetics impulses. Only this time—unlike with the computer-failure fears a few years earlier—we had a hedge of protection.

Back then, Clinton certainly wouldn’t have guarded America from the Antichrist arising, right? Slick Willie may have even chose to cozy up to the Beast. This time, the terrorists had a real foe: the conservative Republican president who invoked God and just-war rationale in defense of the homeland. That’s a big difference.

Real future sociological research may support this speculative statement: the George W. Bush administration alone wreaked havoc with certain Christian end-times expectations. If a literal seven-year Tribulation was still just around the bend, but if the United States was also having a revival of patriotism and conservative culture and maybe even the gospel—then did we expect the end was nigh, or don’t we? This gave Christians in America some deeply spiritual cognitive dissonance.

We kind of felt that enemies like terrorists would create conditions for Antichrist.

But at the same time, we actually, secretly felt we would be okay—for generations.

Show of hands if you ever “pledged allegiance” to this flag (after the American flag).

By the late 2000s, Christian politics began its path to dominating Christian popular subcultures.

Other Christian leaders and publishers might add nuance to my speculation here. Yet by the mid-2000s, I was already full-on participating in Christian popular subculture creation myself, so I’m fairly sure my generalizations will bear out.

As the Bush administration won a second term, I believe Christians in the U.S. grew more embarrassed by our Christian popular subculture trends, angels and concerts and end-times mania and all. Deep down, many of us felt like all that stuff had been distracting us from the serious business of The Real World. After all, the computers hadn’t gone down and America hadn’t blown up. Jesus hadn’t come. Life moved on.

That meant our children and grandchildren might just still grow up and start families. We needed to help build a nation that would stay friendly to Christianity.

Could we do that? Well, on the one hand, we had the Bush administration and general upkeep of conservative morality at the national level. Still, we saw cultural liberals ascending in academia, the news media, and popular culture. Some of our Christian leaders weren’t shallow enough to conclude that politics alone would save us. We realized we would still need cultural strength.

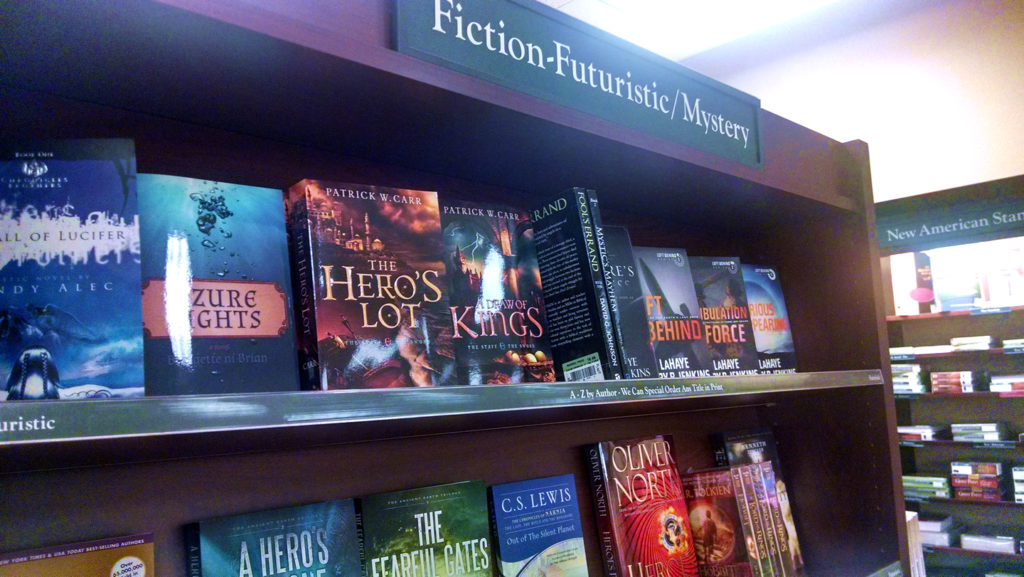

At this point, the evangelicals on Earth-2 wisely chose to use this time to invest their resources in cultivating even better Christian popular subcultures. They built on the Left Behind series to encourage more fiction franchises. They built on VeggieTales to fund not just animation but even feature films, not just for kids but also adults. Finally, they moved in to save bookstore chains like Family Christian Stores and Lifeway, ensuring these didn’t become relics smashed by massive online retailers, but hubs of niche subculture discussion and goods-sharing (likeunto comic book and fandom shops).

Alas. We may have done all that only on Earth-2. Here on Earth-1, we didn’t promote fiction, the franchises, the kids’ series, or the revitalization of Christian bookstores.

Instead, we embraced pragmatism. We bought into promises from political activists and candidates to help us build a better America from the top-down, and the top-down only. Most of us took that shortcut. We dumped resources into forging political movements, political nonprofits, political fundraising, networks, pundits, activism, campaigns, and—after social media’s and Barack Obama’s rises in the later 2000s—debates galore, neverending debates on all our websites and podcasts and platforms.

All these pushed all the other Christian popular subcultures to the margins.

Sure, we had exceptions, like the early 2010s 1990s-throwback-style popularities of devotionals written “in Jesus’s voice,” or the “heaven tourism” books.

But overall, our cultural imagination collapsed. Promising niche offerings, such as uniquely Christian audio drama, went unsupported and thus underfunded. Big Idea Productions went bankrupt and was bought out (yet now it could still come back, thanks to streaming Christian media). “Contemporary Christian music” also lives on, yet often reduced to simpler “worship” tunes that are suitable mainly for churches (where you can’t sing cleverer songs about how they don’t serve breakfast in Hell).

Even if all that stuff earned the same attention, it’s nowhere near the level that U.S. Christians give to politics: candidates, pundits, movements, debates, obsessions.

A rare example of Christian-made fiction found in the wild (at a wild Christian bookstore that appeared, no less). Note the mixture of genuine fantasy titles, by Patrick W. Carr, along with leftover Left Behind thrillers and a few political tie-ins, such as that title near the lower right by Oliver North.

Where does Christian popular subculture go from here?

You may notice I haven’t even caught us up to the present decade. That’s because Christians’ political obsessions—to the detriment of our other popular subcultural pursuits—didn’t start with an orange man announcing his candidacy in late 2015. Our political obsessions also didn’t start either time President Obama won election.

Rather, Christians began obsessing over politics at about the same time we quit having more of our other Christian popular-subcultural trends.

It’s at least a correlation. I’m not sure we can claim one cause led to the effect. Did political obsessions start first, and then encroach onto those other trends? Or did the other trends falter, creating a vacuum for the political obsessions?

That’s for other writers or researchers to explore—I hope with grace and truth.

All I can do is suggest what I observed and begin to see that the change happened.

From here, however, I must conclude with some brief opinions.

I don’t believe this obsession with politics has been for the better. I say this not because of certain radical political movements, or because I claim “the evangelical church must repent” (every one of us? really?) of being a bad witness to the world. God forbid I sound like I’m saying it because I think Christians should be above all that sort of thing. Politics are inevitable. Especially when people use politics as religion, we must engage political controversies as part of living in a fallen world. Some form of redeemed politics may even continue into eternity.5

Rather, speaking as a Christian who believes in glorifying Jesus through all our cultural creations: I contend a Christian popular subculture obsessed only with politics is a weaker subculture. Even if you were a shallow Christian who had turned his faith into a means toward political ends, it would make zero sense to focus exclusively on politics. Even for such a Christian, you must also focus on the rest of popular culture: the stories, songs, games, memes, and imaginations that take that shortcut past the head and into the heart. How much more so, then, should faithful Christians who do make Jesus the chief end—and any political engagement the means—see that Jesus has called us to steward our creative investment in stories, songs, and even film franchises and music bands (however derivative) for his glory?

Over the timespan of generations, a Christian subculture dominated by politics is hopelessly limited and ultimately ineffective for forming more Christlike people.

It’s not all bad, to be sure. The Chosen series alone has many Christians hoping that uniquely Jesus-focused storytelling, gaining mass support, has its best days ahead. Niche streaming services are popping up. Many musicians still find crowds of eager listeners for their songs full of lament and general human themes that go beyond megachurch-appropriate lyrics. And, of course, Christian novelists continue to forge new frontiers in genre-blending and especially fantastical world-building.

This is a fantastic start. But this must lead to more development. We must seriously cultivate this subculture. At some point, we must even firmly and graciously put our feet down and say: “All right, politics, this far shall ye come and no further. We’re going to subscribe to a promising Christian drama streaming service now, and not subscribe to Trump+ or whatever that orange ex-president’s upcoming service will be called. We’re also going to stop doomscrolling Twitter, and instead pick up that promising Christian-made novel.” Oh, and even more practically, we might thank ministries (such as Focus on the Family) who have largely avoided political obsessions and have even kept some funds flowing to Christian-made popular subculture products.

What about the wealthier or more generous donors among us? Once they’ve wised up about what Christian popular subcultures can actually help change people forever and not just every second November, they should start pressuring other Christian groups, with checks in hand, to do more of the same. It will take investment. It will take loss-leaders, and plenty more creative schlock on the way to finding the good stuff (just like the creators of Golden– and Silver Age–era comics).

This is not frivolous. We need this. We need broader, creative, Christian popular subcultures that reflect even the sillier trends of Christians—silly trends that, for all their harm, still apparently limited our political obsessions. Especially if our more-politically obsessed brothers and sisters are correct about our forthcoming doom at the hands of leftists and secularists, we will actually need better Christian popular subcultures now more than ever.

- Here I define Christian popular subculture as that entire “world” of names, bands, shows, tapes, leaders, books, references, and memes known to evangelical Christians, especially Christians in the United States and other western nations. ↩

- Collin Hansen, then with Christianity Today, in 2006 created the term “Young, Restless, and Reformed” to describe a belief system loosely based on historic Reformed soteriology, often called “Calvinism.” ↩

- The last Left Behind series book, the lackluster Kingdom Come (no relation to DC’s 1996 Alex Ross “Elseworlds” miniseries), released in 2007, but the series proper ended with Glorious Appearing in 2004. ↩

- The Left Behind series remains evangelicaldom’s most successful adult-novel franchise, with multiple titles topping the New York Times bestseller list (which did then and does not now count labeled-religious bookseller totals). ↩

- On the New Heavens and New Earth, redeemed saints will receive heavenly rewards and will help steward actual cities and territories on behalf of King Jesus. Stewarding requires some measure of politics, yet without all the greed and power-posturing that marks sin’s corruption. ↩

Perceptive article, though it is somewhat flawed by the author taking on the sarcastic, snarky attitude toward Christian believers that seems to be popular with writers these days.

I must defend the snark to an extent. This I call “gentle snark.” It’s intended to assure readers who are skeptical of the very notion of Christian subculture and might be tempted to think “away with the lot of it; let’s just serve Jesus by participating in the Real Popular Culture.” (This is an absurdity, and denies our spiritual family members a basic “human right” to create cultures and subcultures like any other set of humans.) Anyway, see my other writings for defenses even of “silly” Christian subculture, end-times escapism and all. For example, to this day I remain a Left Behind series fan, though I better see the flaws inherent in some end-times approaches as well as that fiction franchise.

An informed and insightful article. As a Christian author and musician, I pray for a renewal of Christian arts to galvanize hearts and minds, bringing people closer to Jesus.

I disagree with the previous comment that took issue with the ssnark. Anything less than a side-order of snark would not have been as effective in making your points, IMO.

Thoughtful piece. I especially appreciated this line: “Over the timespan of generations, a Christian subculture dominated by politics is hopelessly limited and ultimately ineffective for forming more Christlike people.” That’ll preach, as they say.

We must engage with our culture to understand who lives in the world with which we want to share the Gospel, but when political views *become* our religion (and a nation or its leader(s) becomes a standard to wave above the cross) we become cultists and idolators, operating apart from Christ.

This brings up many interesting and difficult points. I have resolved it to myself as Christians should take an active role in politics, while pastors should keep their preaching to the Bible. Last week for possibly the first time my pastor gave something of a political speech regarding the Capital riots. Getting political was a mistake in my opinion. (And something he has told his staff many times not to do.) Taking a stand on left vs right was his second mistake–by what he chose to say and leave off his political biases were crystal clear. And getting some facts wrong was a third mistake. All of this made his 40-minute Biblical message disappear in the noise surrounding his 5-minute foray into politics.

What a cringeworthy stroll down amnesia lane Stephen. I had all but forgotten Christian Y2K panics. You make some really good points about Earth-2 where we would all be sipping bottles of XYZ while enjoying the fruits of concentrated efforts to produce and create art rather than weaponizing nostalgia to whip of political angst. Sorry. If you find a portal to earth 2 let me know. I keep hoping but my wardrobe is, as yet, just a wardrobe.

In retrospect, I actually left out several noteworthy trends, such as The Shack and a few other cringeworthy examples from the comparatively short-lived “emergent church” fad.