Stephen R. Lawhead’s King Raven Trilogy Optioned for Film Version

Variety reported Nov. 29 that another Stephen R. Lawhead property could see a motion picture adaptation: the King Raven Trilogy.

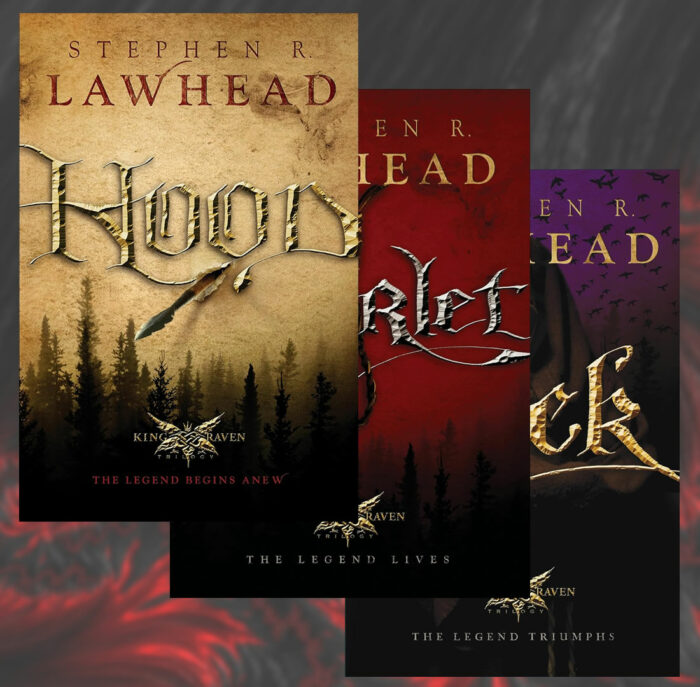

Filmmaker Brent Ryan Green has optioned the film and TV rights to the books titled Hood, Scarlet, and Tuck. Green has spent nearly two decades in the industry, producing films like I Can Only Imagine and American Underdog in the faith and family market, as well as more mainstream projects like Martin Scorcese’s Silence. He is currently working on one of our favorite shows—The Chosen.

King Raven follows the exploits of Bran Ap Brychan, a young Welsh nobleman, as he battles the advancing Norman forces in the depths of the region’s primeval forests. Eventually he becomes becoming Rhi Bran y Hud, and in later ages, Robin Hood.

The news comes as Bentkey films its adaptation of The Pendragon Cycle, Lawhead’s sweeping epic of an ancient Celtic King Arthur.1

How I stepped into the worlds of Stephen Lawhead

This Christmas marks my own 20th anniversary of discovering Lawhead’s works. Since then, I haven’t read one of his books without thinking it should be turned into a movie. They offer such a unique historical angle to their subject matter, without discarding their beloved fantasy elements.

Both of these projects represent Lawhead’s mission to reposition mythical heroes of history into their correct eras or settings. He moved Arthur from the high Middle Ages to the post-Roman Dark Ages. Then he moved Robin Hood from the gentled, deer-park woods of England to the wild and shadowy forests blanketing Wales.

These refreshed contexts, paired with his refusal to ignore his protagonists’ active Christianity, make Lawhead’s books so engaging to Christian readers, especially history nerds like myself.

Lawhead is more than comparisons to Lewis and Tolkien

So I couldn’t help but chuckle when I read Green’s statement on the Raven series: “It’s The Lord of the Rings meets Game of Thrones with the heart of C. S. Lewis.”

Look, I get it. Green is a film producer. He has to raise money. So name-dropping the three sword-slinging fantasy names that actually saw success in the last 20 years is just business.

But Lawhead is nothing of the sort. Though he references Lewis’s Space Trilogy in his Song of Albion, his works are not at all allegorical and have little to do with Narnia. They don’t have the carnal, hopeless tone of Game of Thrones. And they’re about as far from Tolkien’s Middle-earth as historical novels can get.

When storytellers fall back on referencing the Big Three of fantasy, this has less to do with inaccurate comparison and more to do with Hollywood’s failure to launch any other successful sword-and-sorcery franchises. Nearly everything from Eragon to Amazon Prime’s The Wheel of Time has gone down in flames, mostly for failure to honor the source material and a lack of respect for the audience.

This is why I’m hopeful for these Lawhead adaptations.

Green and Boreing are obvious fans of Lawhead

“It’s been more than 15 years since I first read Hood, and the desire to adapt this incredible work for the screen has always been with me,” Green said. “The series impacted me in a way few books have.”

Pendragon Cycle producer Jeremy Boreing has given similar praise to Lawhead.

Lawhead is a successful author, but has never had a massive audience like Lewis, Tolkien, or Martin. He’s not in the zeitgeist, as much as I think he should be.

So it’s not like Boreing and Green are cashing in on a fad. Instead, they’re correcting Hollywood’s two biggest flaws regarding fantasy: They want to honor the source material because they love it, and they’ll respect the audience because they are the audience. This sounds like Peter Jackson’s attitude toward The Lord of the Rings. I’m beginning to wonder if we’re on the verge of a fantasy renaissance in cinema.

- DailyWire+ is posting production videos, yet the company has spun off a new story-focused streamer called Bentkey. This is the Daily Wire’s parent company, and is so named after founder Jeremy Boreing’s memento of a childhood theater. ↩

Share your thoughts, faithful reader (and stay wholesome!)