Sensual Scenes in Fiction Pose Unique Temptations for Women

From Twilight to Divergent to our own Lorehaven library of Christian-made fantastical novels, you can find varying doses of sensuality.1 In fact, the combination of romance and fantastical elements is one of the largest draws for female readers to these genres. Instagram alone features new marketing strategies emphasizing the types of romance readers will encounter, rather than plot elements. (“Check out this enemies-to-lovers, slow-burn paranormal romance!”)2

Is this morally neutral, or would this provoke lust in the majority of female readers?

Women are struggling with sensuality in fiction

I’ve spoken with countless women struggling alone with lust, believing they’re the only ones tempted in this way. That’s one of several dangerous lies Christians have allowed to spread in our churches.

Both men and women assume only men are tempted to lust. We fail to grasp the differences our gender-specific makeup creates in our temptations and that all of us are sexual beings. The longer these lies spread, the longer women will continue to suffer alone and unaided, even allowing their consciences to grow dull about the stories they read and see.

It may be that fewer women struggle with sensuality in books than men struggle with visual pornography. But I have spent the last twelve years speaking to women about their struggles with lust and porn. I have interviewed many personal friends and acquaintances as well as online friends and strangers. I have even given online surveys to try to ascertain the extent of this temptation, and written two articles (here and here) for DesiringGod.org.

I feel safe estimating that at least 60 percent of women have this temptation. Personally I think the number is higher since many women are not comfortable admitting they struggle with lust. Some have also dulled their conscience to this sin because their “symptoms” don’t resemble a man’s.

Christians often deeply misunderstand what lust looks like for women, since we’ve traditionally defined this sin through men’s eyes alone. We may stereotype men as always being visual and never being emotional about romance, and vice-versa for women. This isn’t always true. Women can be visual and men enjoy emotional romance. But for the sake of simplicity, I will use the generalization that women tend to prefer emotionally intimate erotica, and that men usually choose visual pornography.

But what kinds of symptoms would we expect to see for lust in women?

How Jesus gently exhorts the Samaritan woman at the well

Jesus condemns all lust when he introduces a heart-based ethic over the traditional law-based ethic of the Pharisees: “You have heard that it was said, ‘Do not commit adultery.’ But I tell you, everyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart” (Matthew 5:27–30).

Christ’s command helps us understand lust’s severity, emphasizing heart motives rather than outward actions. He is also clearly targeting men. His words “looks at a woman” implies the male tendency to lust after a woman because of her appearance. But we have interpreted this passage in a way Jesus never intended—that lust is only a man’s problem and that looking is the only way to commit this sin. What a serious error. And what damage this assumption has wrought on us.

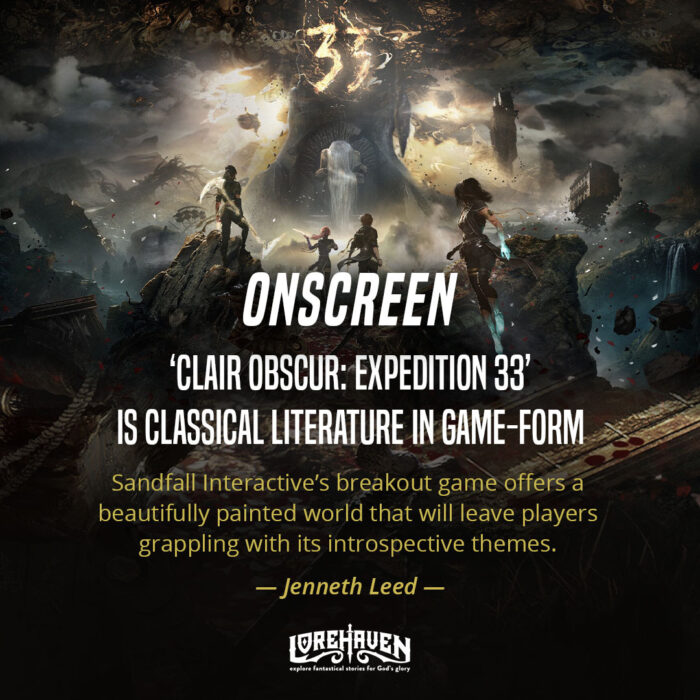

Jesus gently but firmly confronted a Samaritan woman who was entangled with sin (John 4:1–42). (Image from The Chosen season 1 episode 8, “I Am He”)

I’ve wondered why Christ didn’t give specific instructions for women about lust. But what do we know to be true about Jesus? He values women and doesn’t neglect us. In fact, he spoke explicitly to a hurting, sinful woman on a closely related topic as she was drawing water from a well (John 4:1–26). Jesus offers living water to this woman, who had been married five times and was living with a man who wasn’t her husband. He broke tradition to speak to this Samaritan woman who was caught in a life of searching and not finding.

Typically, women who read romance feel drawn to emotional connections between characters. As single teens or even married women, we long for a relationship with a man we love, looking at us and treasuring us as his own. Relational closeness is a beautiful gift of God. But this gift can easily become an idol. For women, this idolatry can be equally as common as men’s tendency to lust by objectifying a woman’s body.

Jesus sees into the heart of this Samaritan woman. He sees what she’s looking for and he knows she won’t find this, no matter how many men she sleeps with or marries. She is chasing wind (Ecclesiastes 1:14) as she searches for a man to fill a void that devours connections and relationships and is never satisfied.

So what does Jesus do? He sees her thirst and offers her living water so she’ll never thirst again. And he is that water—the ultimate bridegroom. In Christ alone can she be satisfied and be treasured (and treasure him) beyond what she could deserve or imagine. In Christ alone will her cup overflow (Psalm 23:5). No other man or relationship will fill that need.3

How sensuality can ensnare female readers

What does Scripture say about sensuality? One website suggests:

In the Bible, sensuality is usually listed with other evils that include sexual promiscuity and perversion. Also known as “lewdness” or “debauchery,” sensuality can be defined as “devotion to gratifying bodily appetites; free indulgence in carnal pleasures.” The word sensuality comes from the root word sense, which pertains to our five senses.4

I define sensuality in fiction as descriptions of bodily “senses” of attraction and/or arousal. This means “showing” and not “telling” that a person is attracted or aroused through touching and/or kissing using descriptions of external and internal bodily sensations.

Some men may stumble when reading outright sex scenes, but have fewer problems with sensuality. Remember Jesus’s lust warning in Matthew 7, which exclusively addresses a man lusting by looking at a woman. Women can lust in the same ways, but we are less likely to form addictions to visual pornography. Why is that? Because women (as in John 4) tend to fall for relational and emotional temptations with sexual sin. This element is present in movies, but it’s often more intimate in books.

Meanwhile, modern writing styles (such as deep point-of-view) bring out even more depth and seek to place readers into the mind, eyes, and even body of the point-of-view character. This can be an effective creative tool. As a writer, I use it myself, because this style helps readers to feel exactly what the characters feel, more than classic literature and certainly more than biblical accounts. (This includes the Song of Songs, which contains metaphorical descriptions of sensuality). But using this tool may be dangerous, by causing readers to feel attracted and even lustful toward a story’s love-interest or envious of the couple’s emotional and physical connection. When readers emotionally invest in fictional relationships, deep point-of-view style can increase emotional tensions in unhealthy ways.

We can’t dismiss this threat with ‘weaker brother’ defenses

Should we make this caution against sensuality into universal law (a habit I dislike, because this generally leads to legalism), or should each reader discern if she is individually tempted?

In most of my bookish circles, I often hear people answer such moral dilemmas by pointing to the “weaker brother” argument. This refers to 1 Corinthians 8:7–13, where Paul tells the church that members may eat food sacrificed to idols, but not in front of people who may spiritually stumble—brothers with a weaker conscience. When Christians discuss moral issues when creating media, they often use this weaker brother argument, explaining that it’s impossible to always cater to the weakest Christians.

I don’t believe this “weaker brother” argument applies to warnings that fiction sensuality tempts female readers to lust. For the moment, let’s set aside the issue of movies’ objectification of real women, and use the following as a thought experiment. This argument would be similar to saying, “It’s okay to have nudity in films, because leaving it out would cater to the weaker brother.” This statement doesn’t stand since most men would be the weaker brother. (However, this is still a matter of prudence and not law, since a woman who is truly not tempted by sensuality can read a steamy book and not sin.)

As I mentioned earlier, because I’ve seen that at least 60 percent of women struggle with this, I believe the weaker brother argument doesn’t apply and is often abused in this conversation. More importantly, an obsession and coveting (Ephesians 5:3) of the emotional connection between characters is a gateway drug into a struggle with sensuality in fiction (which then may lead to a true porn addiction). I believe this coveting of fictional connections is just as common as a man’s struggle with pornography. This sin is capable of removing all sensory feelings we normally associate with lust. That’s how the sin becomes sneakier, yet leaves us vulnerable to the same wind-chasing as the woman at the well. But while she tried to fill her heart’s longing with multiple sexual partners, we as readers are left attempting to fill our hearts with connections to fictional people. It’s this emotional lust that very rapidly turns into a full-blown addiction to erotic novels.

This kind of heart-sin takes a potentially edifying gift, such as fictional romance, and turns it into a drug for our idol-factory hearts.

Fictional romance should to point us to Jesus

What’s the goal of good and edifying romantic fiction?

Like the woman at the well, we are searching for a good we can only find in Christ. Her first marriage was not bad. It mirrored the relationship between Christ and his church, not a covenant we enter selfishly, but for our good and others’. Like our marriages, the church’s marriage to Christ brings common good. The world uses that phrase to describe social betterment. But the Church’s historic use implied the good we contribute to a team, such as the Church itself or a marriage.

When we read romantic fiction, are we attempting to fill our cups and quench our thirst with something other than Christ? Or are we relishing in a character’s joy as it mirrors Christ and the Church?

If you can’t tell the difference, pretend you’re attending your best friend’s wedding. You are overjoyed, emotional, teary, and all fluttery inside because of the joy she is experiencing. You’re not jealous or living vicariously as though her wedding was your own. Your whole heart is caught up in her happiness. Suddenly her happiness has become yours, an emotion that is pure, beautiful, and God-glorifying.

Can you feel the difference in your heart as you imagine this scenario?

This is the kind of joy romance in fiction should produce when we celebrate someone else’s happiness and the common good of their relationship. This joy does not steal pleasure for our own selfish titillation, but multiplies the blessing of marriage to everyone, bringing you closer to Christ in the process.

- Photo by Christina Rumpf on Unsplash. ↩

- This article has been lightly revised by the author as of Feb. 10, 2025. ↩

- Note: The Bible certainly values sexual purity. But to avoid one of the biggest pitfalls of evangelical “purity culture,” note that sexual purity doesn’t justify you before God, and impurity won’t remove God’s grace from you. Purity is important for holy living, but it won’t save you. Only the blood of Christ can truly purify all of you. For an in-depth look into purity culture, I highly recommend the book Talking Back to Purity Culture by Rachel Joy Welcher. ↩

- “What does the Bible say about sensuality?”, GotQuestions.org, undated article. ↩

I like the example at the end, are you attending your best friend’s wedding, or imagining you’re in the wedding?

Thank you for this. I have struggled with lust for years, mainly aided by books and TV. I know to look at reviews before watching now, but books are a lot harder. Even books marketed as Christian get uncomfortable sometimes and it’s often hard to know which those are without stumbling into them. By then, my emotions are already engaged and it’s hard to stop.

Wow now I understand why some romantic books feel so “happy” and others don’t, some are like seeing two friends falling in love and it fills you with happiness but if it’s not like that and you wish you were the protagonist or you live through it it’s wrong .

Thanks for this, Marian. I always find your articles thoughtful, and this needed to be said.

Thank you so much for including the note on purity culture. It is SO difficult to address a topic like this without sliding into legalism, but you handled it with a light touch.

That was really eye-opening, especially the example of a friend’s wedding. I hadn’t realised what a difference there is… Thank you 🙂