Love Transforms the Beloved in ‘Beauty and the Beast’ Stories

“Beauty and the Beast” is my favorite fairy tale. I’ve loved it since I was young and watched the Disney animated film (one of my earliest memories). The concept of transforming love—love that sees deeper than surface ugliness, that changes its once-unlovable object into something worth loving—was powerful. My appreciation for that kind of love has only grown. It is a type or mirror of God’s love for us. We who were once the most wretched of sinners, beyond any reason of love, have been transformed by the blood of Christ into God’s beloved children.

Our notion of the fairy tale has been diluted over the years, thanks in large part to the Disney film and other abridgments. (In fact, when we studied the tale in my college folklore course, we read Beaumont’s abridgment instead of Villeneuve’s original.) It has become a story about the beastly prince who is made princely by Beauty’s love.

But the original worked a little differently.

In Villeneuve’s story, the Beast’s crime was not refusing an old woman at the door but refusing his wicked fairy godmother’s amorous advances. Yes, he told her (truthfully) that she wasn’t beautiful, but he also rejected her proposal of marriage. For that, she cursed him to be monstrously ugly, a curse that would only lift when he could win the love of a woman without relying on his title or riches.

Enter another fairy godmother, who gives the Beast a plan to save the day. This particular fairy actually pulls quite a few strings in the background of the story. (All of this is revealed after the curse is lifted. Villeneuve goes on for another tale’s length after the transformation, detailing all the background of the Beast and Beauty, who it turns out is the daughter of yet another fairy godmother.)

But the Beast is not the one who changes (aside from his appearance and perhaps a lesson in tactfulness). It is Beauty who is forced to confront her own shallow perceptions, recognizing the prince beneath the beastly exterior.

Some modern versions of the tale (Shrek, Robin McKinley’s Rose Daughter, Mercedes Lackey’s The Fire Rose, the two urban fantasy Beauty and the Beast TV series) have eschewed the final physical transformation of the Beast, focusing on the interior aspects of the tale (and at least one version by Angela Carter actually flips this moment to make Beauty physically like her Beast, much like Shrek). This is due in large part to the modern emphasis on physical beauty being fleeting and deceptive 1, but it also presents some interesting questions: would we love the story as much if the prince didn’t return to his handsome appearance at the end? What do we lose (and gain) by changing the symbolism of transformative love?

The first time I was confronted by the idea of love going deeper than appearances, even in the face of a transformation being denied, was in the Disney Aladdin TV series. In an episode titled “Eye of the Beholder,” one of Aladdin’s enemies tricks Princess Jasmine into using a cursed lotion that transforms her into a hideous snake creature. 2 The only cure is fruit from a tree hidden far away in a protected valley. Aladdin, Jasmine, and their friends embark to find the tree. Along the way, Jasmine’s snake form shows its uses; she frightens off attackers, and at one point she even saves Aladdin from a deadly fall, although her tail’s venomous spikes end up wounding Aladdin in the process.

When they finally arrive at the valley, they find that their enemy has already killed the tree that would have cured Jasmine. Faced with a lifetime without Jasmine, Aladdin chooses the one thing his enemy failed to foresee: he uses the same cursed lotion to transform himself into a snake creature. Even if they have to live away from the rest of the world, they can be together. The enemy’s plans are frustrated, and another enchanter takes pity on the lovers and heals the tree. Aladdin and Jasmine eat its fruit and are restored.

Even though this story seems on the surface to work against the symbolism of transforming, redeeming love, it actually paints a compelling picture of another aspect of Christlike love: self-sacrifice. Aladdin chooses to become as his beloved is, willing to give up everything else in his world to be with her. It is not unlike Christ’s parable of the shepherd leaving the ninety-nine sheep to find the one that was lost.

No matter the form it takes or the new twists a retelling spins, “Beauty and the Beast” remains at its core a tale of love that redeems its object and brings two people together who might otherwise have been separated by their own sins and the sins of others.

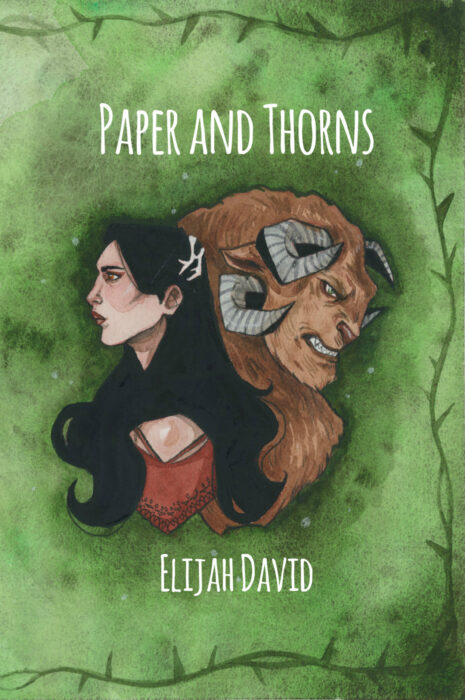

Elijah David’s own “Beauty and the Beast” story, Paper and Thorns, is available now at Amazon, at Barnes and Noble, and at other book retailers.

Yes!! This is why I like Beauty and the Beast so much, especially the original. It’s not just Beast who has to change, but Belle as well, and the moral of the story is lost among the shallow, first impressions of it. There is a reason why the phrase “don’t judge a book by its cover” is common. Unfortunately, in this day and age of Instagram and Twitter, the cover is only what some people will look at.

It really is a shame that people forget that everyone can grow and change and become a better person, even in story worlds.

Wow, that’s a great analysis. I forgot all about that episode of the Aladdin and Jasmine series. Thanks for reminding me, since I know I completely missed the meaning as a child.

You’re welcome. That episode has stuck with me more than most. I’m surprised Disney hasn’t put it out there on Disney+ with so many other shows from that era available.

This is my favorite fairy tale also, and it’s amazing how much you can learn from it and the many different versions that exist. I love both of Robin McKinley’s Beauty and the Beast retellings they are done so well.

Yes, McKinley’s versions are very well done, although I do wish the ending of Beauty didn’t feel quite so rushed.

Great article! Beauty and the Beast is my favorite fairy tale as well, and now I’m very curious about the Villeneuve version!

It is fairly inexpensive on Kindle. This is the translation I read (only $0.99): https://www.amazon.com/Beauty-Beast-Gabrielle-Suzanne-Barbot-Villeneuve-ebook/dp/B00KAFDLUQ