‘The Seventh Sun’ Reflects Our Need for Relatable Non-Christian Characters

Some critics too easily claim that Christian-made stories often portray characters with non-Christian beliefs in cartoonish ways. You might already know the stereotypes: the villainous atheist, the angry Muslim, or the scheming liberal.

These figures may appear in evangelical movies. Contrary to some critics’ charges, such characters aren’t terribly widespread in Christian-made novels. But even when these novels don’t turn non-Christian characters into cartoons, the novels don’t always present compelling arguments for the non-Christian’s position.

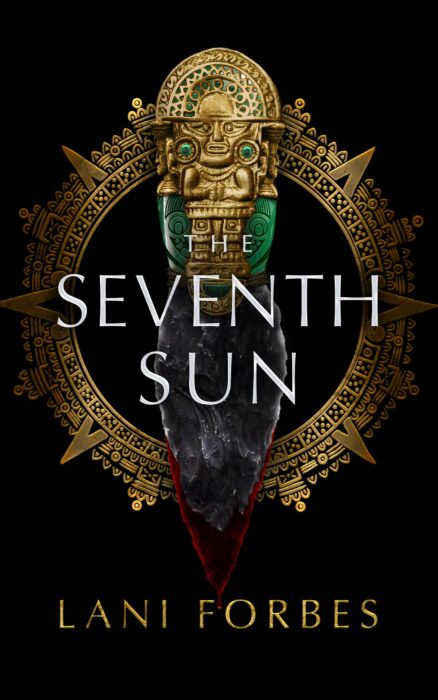

Lani Forbes’s Mesoamerican-inspired fantasy The Seventh Sun is one book that does present non-Christian characters who are complex and sympathetic—and even dares to portray people who defend human sacrifice, of all things.

As I’ve reflected on Forbes’s fantasy world after her tragic passing in February 2022, I keep returning to this strength of The Seventh Sun: Forbes portrayed non-Christian characters in relatable ways. She reminded us of important truths we as Christians need, especially when pundits insist we view our opponents as malicious enemies.

The Seventh Sun dares us to honor human-sacrificing heathens

To summarize the book (without spoilers!), The Seventh Sun focuses on seven princesses seeking to win the heart of a newly crowned prince. The six princesses not chosen will be sacrificed to appease the gods. (Read Lorehaven’s review.)

To summarize the book (without spoilers!), The Seventh Sun focuses on seven princesses seeking to win the heart of a newly crowned prince. The six princesses not chosen will be sacrificed to appease the gods. (Read Lorehaven’s review.)

One princess, Mayana, has always doubted the sacrificial system and wants to see this end. But her new best friend Yemania, one of the rival princesses, surprisingly supports the sacrificial system, despite her odds of being sacrificed herself. During one pivotal conversation, Yemania defers to the gods: “The gods sacrificed themselves to save us. We owe them blood. … Do you think you know better than the codex? The holy texts given to us by the gods thousands of years ago?”

When Yemania is challenged about how she could uphold such a tradition, even when it demands her death, Yemania further stands her ground: “You think it requires bravery to question the rituals, but it takes me just as much to obey them when everything inside you doesn’t want to.”

That’s a surprising amount of moral resolve for upholding this custom.

Despite Mayana’s repeated attempts to persuade her otherwise, Yemania stands her ground throughout the story. She even responds angrily when Mayana tries to spare her life: “I don’t want the prince to think that I am not willing to do my duty.”

Readers may find it hard not to like Yemania, given her caring heart and her befriending of Mayana when other princesses view her as only a rival. And despite the awful system Yemania upholds, you might also understand her perspective, given her cultural beliefs. As The Seventh Sun ends, the story leaves Yemania unpersuaded by Mayana. In Yemania’s resolve, she becomes a fascinating case study into the value of portraying non-Christian characters sympathetically.

Relatable non-Christian characters help us respond to real people

Christian readers may view relatable non-Christian characters with suspicion. After all, if authors make certain characters too relatable, couldn’t readers feel their minds changed by the characters? This result seems unlikely, but such critics make a valid point: fictional antagonists can persuade some readers. Reading such books does bring real risk. But we also face this risk by simply engaging real life. If fictional characters’ beliefs can change a reader’s minds, that reader probably wouldn’t fare much better against a real person with similar beliefs.

But in the right author’s hands, stories with relatable non-Christian characters can actually provide us safer places for training to respond to such beliefs. Without the pressure of immediate response in real-world conversations, we can often develop better answers for our Christian beliefs.

As my old high school literature teacher said, we best learn how to respond to unbiblical beliefs not by sparring with “straw man” variants, but by learning how to rebut these beliefs’ “steel man” version.

Forbes has an easier task. The Seventh Sun probably won’t tempt modern readers to support human sacrifices. But the principle applies to all books—whether they deal with unfamiliar moral challenges or challenges that we do face.

We need books with relatable non-Christian characters because these figures can best prepare us to respond to real-world people.

Relatable non-Christian characters help us see their humanity

In our increasingly polarized world, we can too easily make uncharitable assumptions about our opponents. Evangelical movies (yes, such as the infamous God’s Not Dead) don’t help by portraying Christians’ enemies as cartoonish jerks.

Stories like The Seventh Sun portray such people more sympathetically, reminding us that people are neither simple collections of beliefs and arguments, nor the Devil incarnate. Behind all these is a very real human being bearing God’s image. When we see this truth, we follow Christ’s call for us to imitate him by loving our enemies, so we can engage with them with compassion and love—while still standing up for what’s true, noble, and good.

We can trust God with our hard questions

A few months before The Seventh Sun author Lani Forbes passed away, I shared a conversation with Lani about her portrayal of non-Christian characters. She said something that deeply resonated with me: “I’m never afraid to dive into things to find the answers because I always find the truth. I’m a firm believer to not shy away from the hard questions. Because God will meet you there when you do so.”

Relatable non-Christian characters give us the chance to wrestle through hard questions. As I ponder Lani’s life and work, this truth stands out to me: her trust in God to ask him hard questions, knowing he would always give her the answers.

Want to explore The Seventh Sun? Join our March 2022 Book Quest exclusively in the Lorehaven Guild. Learn more about the quest and how to join the Guild on Discord.

For my weeb dweebs: Crunchyroll sponsored an anime-ish project (depends on how you define “anime”) called Onyx Equinox that is a fantasy version of pre-Columbian Central America, but is super not-for-kids for reasons about lots of blood and what happens to get humans to leak all their blood at one time. It seems…good? based on the couple episodes I watched, but the downside is that it’s somewhat undermined by its budget of about two shoestrings.

Secondly, Imma use this article as a jumping off point to talk about the dance in characterization between how people actually act and how people should act (that “should” does a lot of heavy lifting). Christian fiction tends to lean hard into the “should” category, to the point that it stomps over any trace of verisimilitude. On the other end of verisimilitude at the expense of likeability is works like 1984, but that is why it is Important rather than Popular (and how verisimilar it is is up for debate.)

TL;DR: it’s the reason why Jane Austen has kept and gained clout over Sir Walter Scott even if he was more popular at the time of their contemporary publishing. Jane Austen wrote characters, while Scott wrote tropes (even if most of them were noble tropes). And once those tropes fall out of fashion, his plot-muppets (I hesitate to call them characters) seem less noble and exemplar and more quaint, irrelevant, or cringey.

I’m struggling with understanding the issue here. Is it that Christians should be careful to include de-stereotyped non-Christian beliefs in their stories? I can see that, although you’re saying that it happens already, just not on the popular evanjellyfish stories. The literary world at large is awash with sympathetic non-Christian characters. It’s all you really read about. The bigger issue is the cartoonish depiction of religious authority figures and religious belief in secular stories, though that’s not something this post address. That issue is really out of our hands, and we shouldn’t expect those writers to contradict the world inside their heads with pleads of “being fair,” because no one cares to play fair except for evanjellyfish.

Lol, I might have to steal “evanjellyfish,” but in my experience, they don’t have problems about complaining about much of anything, they just generally take the passive-aggressive route. They still have plenty of stinging cells.

So I’m taking more of a reader’s perspective here than a writer’s perspective, but I am arguing that it’s valuable to read stories with “de-stereotyped non-Christian beliefs”–particularly Christian stories. Unfortunately, as you said, secular fiction does often depict Christians in cartoonish and non-stereotypical ways, and that’s a problem!

I’d be curious as to how this conversation intersects with the cultural appropriation debate. Many of the Goodreads reviews for The Seventh Sun are very negative regarding Forbes’s handling of Mesoamerican culture and characters, in great part because she’s a white author and her own culture/beliefs are evident in the story (which many argue disrespects the culture that inspired her work). Yet at the same time, as your article just mentioned, Forbes may make some Christians uncomfortable (in a good way) causing them to relate to and sympathize with people who believe something that is clearly false and destructive (which is a much stronger foundation for evangelism than mockery of cartoonish unbelievers). Cultural appropriation is a massively complex topic (I wrote my senior paper on it, and I still don’t claim to know where to draw the line). I don’t know if you want to open that can of worms in the comments section–feels like an article of its own. I’d be interested on your thoughts, though!

Heck, this is my jam, I’ll throw my two cents in.

Some amount of that criticism is inescapable, because she is a whitey from a dominant culture who manipulated a real minority culture to suit her own ends. And that is okay, that she is being criticized because of it.

But it’s possible that she may have been able to escape some of that criticism if, maybe, her research into Mesoamerican culture showed in a well enough light or if she was respectful enough of the culture (which is such a moving target I wouldn’t count on it). It may be that the narrative voice is super condescending about Yemenia’s understanding of blood sacrifice even if it admires her integrity towards her duty, I dunno.

I intentionally avoided getting into that debate in this article since that’s a separate issue I don’t feel particularly well-qualified to talk about in a full article. In brief, though, I thought that certain accusations were overblown while others were legitimate criticisms. Since the story was set in a fictional world, I wonder if the worldbuilding would make more internal sense (and avoided many of the cultural appropriation charges) if it had used completely fictional gods instead of trying to depict real gods people worshipped in a secondary world and merge different cultures together. I think there’s legitimate critiques to be raised about that story choice–though I don’t think it should deter from everything else that’s great about the story. I was, however, peeved by some of the reviewers who said it was cultural appropriation to depict human sacrifice as being evil (as the book does). While cultural appropriation can be a real problem, the trampling of human rights should be condemned no matter what culture does it.