How Stories Physically Reshape Our Brains for Good or Ill

Fantasy authors like J. R. R. Tolkien argued it was their duty to help readers “escape” through books.1 But has speculative fiction changed since Tolkien’s declaration, or have readers? What does escapism in fantasy look like today? Is this still good and defensible? Or do our favorite books change our brains—for better or worse?

In the past few years, I’ve overhauled my diet. That’s not because I was chugging soda every day or was chastened by the dentist for yet another cavity. I had convinced myself that my diet wasn’t too bad. After all, I still ate plenty of fruit and vegetables, and although I preferred burgers over salads at restaurants, I felt I’d made more good eating choices than splurging.2

But scale results and blood test figures told another story. I had developed pre-diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and chronic inflammation—the beginnings of an auto-immune condition. Its progression later forced me to quit my job overnight.

My poor diet wasn’t the only cause of my symptoms, but it definitely exacerbated the problem. I was eating way too much processed food with too much sugar and salt. And, thanks to the declining quality of ancestral soils, the veggies I was eating had nowhere near the nutritional value of veggies decades ago.

More stories are taking sugary shortcuts to please our tastes

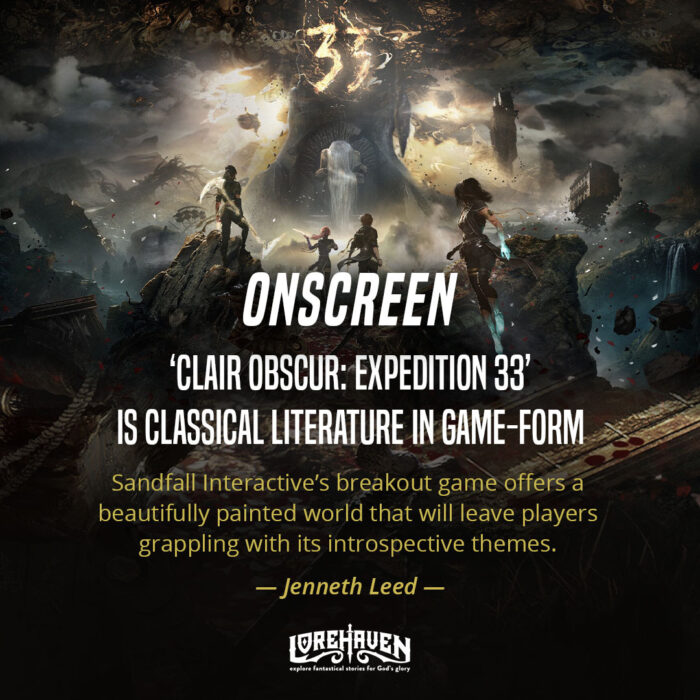

In recent years, the socio-cultural intake of the West has changed as much as our food preferences. As many have noted, audiences increasingly prefer films that “fall lighter on [our] brains.” Hence the recent proliferation of live-action remakes, reworkings of old classics, or movies inspired by toys and video games.

Cognitive shortcuts3 also abound. Marketers sell more fantasy books using the “X meets Y” formula. Or they use checklists of beloved tropes like “enemies-to-lovers,” “grumpy/sunshine,” and “he falls first.” Thanks to our overstimulated brains, world-weary souls, and emptier wallets, we’re less likely to risk uncharted territory or unproven authors. Instead we revert to nostalgic tropey fandoms or reimagined fairy tales. We want escapist entertainment. But we also want traces of the familiar amidst the strange.

Do readers really have a duty to escape?

Responding to criticism that fantasy was inherently escapist, Tolkien famously said:

Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls? The world outside has not become less real because the prisoner cannot see it.4

Author Ursula K. Le Guin famously paraphrased this argument in the now-famous quote (often wrongly attributed to Tolkien himself):

Yes, he said, fantasy is escapist, and that is its glory. If a soldier is imprisoned by the enemy, don’t we consider it his duty to escape? The moneylenders, the knownothings, the authoritarians have us all in prison; if we value the freedom of the mind and soul, if we’re partisans of liberty, then it’s our plain duty to escape, and to take as many people with us as we can.5

But since Tolkien first issued the call for readers to escape, and LeGuin urged them to bring other prisoners-of-war with them, the landscape of fantasy has changed.

YA fantasy alone has dramatically changed from the books I read in high school. In the past 20 years, the genre has undergone slow pornification. Bestseller lists are now dominated by erotically charged fae romances more reminiscent of Fifty Shades of Grey than The Lord of the Rings. Even “clean” or Christian fiction is not immune to an increasing sensualization, which poses unique challenges to and temptations for audiences who may consider this content neutral or benign.

Stories really do reshape our neurochemistry

But it’s not just fantasy that’s changed. Readers have changed. Our favorite stories do reshape our brains, and not just for readers of erotic content or romance.

Neuropsychologist Donald Hebb famously said, “Neurons that fire together, wire together.”6 That statement now underpins modern neuroscience. When you repeat an experience—or a thought or action—the brain forms neural superhighways that make the brain more likely to activate that pathway.

This idea explains why the brain can learn new ideas at any age (neuroplasticity). We see how addictions form, because dopamine reinforces mental association. And we know why erotic stimuli is so very damaging for the human brain.

As writer Will Durant puts it, building on the writings of Aristotle: We are what we habitually do.7 If you, like me, read a lot, your mind and behavior is influenced by your reading. Favorite books constitute your socio-cultural diet and affect your psychological and physiological states. Like sugar and carbs, which generate cravings for more sugar and carbs, the books you reach for will produce cravings for similar kinds of books, which in turn reinforce your preferences for those books.

In hard seasons, don’t just escape—seek better nourishment

Please don’t assume I’m some kind of health warrior who brings celery sticks and hummus to the cinema and extols the virtues of colloidal silver. Occasionally I still eat junk food and enjoy a just-for-comfort book. To paraphrase C.S. Lewis, if the book does not celebrate pride, lust, or immorality, it’s not necessarily a bad book—books need not all be overtly moral or religious.8

But these days, just like I’m more aware of what substances I put into my body, I’m more aware of what I’m feeding my mind. I’m aware of my vulnerabilities that lead to those comfort-food desires. I know that when I’m sick, or else craving cheese toasties or ice cream, I instead need the nourishment of chicken soup for my body and spiritual “food” for my mind—best of all, the Bible.

Either sort of nourishment rewrites my neural pathways. My brain learns that when I’ve had a hard day, I don’t always need comfort food or an imaginative escape. Instead I can reach for a book that helps me lean into discomfort and find healing. This improves my emotional resilience and changes how I respond to hardships.

What about escapism that isn’t romance or that kind of romance?

Even if you don’t struggle with the escapism of erotica or sensual stories, you might have experienced the tendency to revel in “safe” or “easy” stories. Even the reverse of this, like hard-hitting tales that cause you emotional turmoil, can bring the same results. Either way, here are some questions to consider:

- Do you only read books with particular tropes or by particular authors?

- Do you prefer simple/shorter rather than more complex/longer stories? (Note: Longer doesn’t always mean more complex, and shorter doesn’t always mean simpler. George Orwell’s Animal Farm is an excellent example of this.)

- For nonfiction readers, do you only read books by authors you agree with?

- For fiction readers, do you only read books with happily-ever-afters or known/formulaic endings? (This one is a particular weakness of mine.)

- Do you prefer books that “wreck” you or make you anxious? (Lorehaven staff writer Marian Jacobs provides a fascinating exploration of this topic here.)

Different needs call for different books

Once again, I don’t believe it’s bad to reach for familiar or comfort stories, or to re-read beloved classics. For instance, you might not break out War and Peace while undergoing chemotherapy. The poet W. H. Auden once argued:

There must always be two kinds of art: escape-art, for man needs escape as he needs food and deep sleep, and parable-art, that art which shall teach man to unlearn hatred and learn love. 9

These choices call for wisdom. In a cultural landscape that now heavily promotes escape-art over parable-art, what stories do you prefer the most? What fictional influences do you permit to shape your brain and therefore your behavior?

Finding your way to nourishing reading choices

We need all many kinds of stories to grow, both the familiar and the strange—the kind of strangeness that helps us make sense of the familiar. Fantastical stories are exceptionally good at offering us both.

This year, I encourage you to examine your cultural diet, just as my doctor once evaluated my actual diet. No judgment. What is your protein (which keeps you feeling full for longer)? How nutritious are your fruit and veggies? Do you live on pasta and cheese toasties? What do you crave when life gets tough? Do you always reach for what you feel like and never for what your body really needs?

As J. K. Rowling said, “The stories we love best do live in us forever.” Consider the stories that live in you, and whether they make your mind and spirit sick or healthy.

- Cover image by Hal Gatewood on Unsplash. ↩

- In psychology, we call this phenomenon “cognitive dissonance.” But intellectual familiarity with the phenomenon makes us psychologists no less immune to it. ↩

- In psychology, we call cognitive shortcuts “heuristics.” ↩

- J. R. R. Tolkien, “On Fairy Stories.” ↩

- Ursula K. Le Guin, The Language of the Night: Essays on Fantasy and Science Fiction (1979). ↩

- D. O. Hebb, The Organization of Behavior: A Neuropsychological Theory (1949). ↩

- Will Durant, The Story of Philosophy: The Lives and Opinions of the World’s Greatest Philosophers (1926). ↩

- C. S. Lewis, On Writing (and Writers): A Miscellany of Advice and Opinions, page 119. ↩

- W. H. Auden, “Psychology and Art To-day.” ↩

It is sad that although not every book that is not overtly religious or moral is bad, it is true that many books today are downright immoral or bad.

Thank you for this outstanding article, including all its reflective prompts. I would love to see this kind of thing more often.

This article is much appreciated. Over the years, I’ve become sensitized to how fiction pieces make me think and feel. On the one hand, a surprising number of Christian novels leave me feeling confused, empty, and even disturbed, while on the other hand, the scriptures are becoming more impactful. My happy place (aside from the Bible) seems to be the classics created from within the Judeo-Christian worldview. And my “weakness” for happy endings? That’s part of my healthy diet.

I am thankful for this eye-opening article Jasmine, but at the same time I am disheartened. Like many, I’ve noticed the gradual pornification of secular YA literature. But in Christian fiction? It was particularly upsetting to read about the sensualisation of Christian fiction. I am reminded of the experiment with the frog in the pot of boiling water: the temperature rises so gradually that the frog doesn’t realise it’s being boiled alive until it’s too late!

This incremental heating seems to have crept into our Christian narratives as well. What began as harmless romantic prose—hand-holding and kisses—has escalated to mirror narratives we find in secular bookstores. This is a wake-up call prompting us to jump out of the pot before we are overcome. Psalm 1:1 warns us, “Blessed is the one who does not walk in step with the wicked or stand in the way that sinners take or sit in the company of mockers.” Are we, as a community, gradually losing our blessing by not distancing ourselves from secular influences? Have we slowed our run to a walk, or worse yet, have we stopped to stand or sit comfortably amidst the filth?

It seems we may be partaking more of the world’s diet than we realise. If this is the case, let us regain our sense of holiness. Let’s resolve, like Daniel and his friends in Daniel 1:8 – 20, did—to maintain a diet that upholds our values. They chose not to defile themselves with royal food and wine, and God rewarded their prudence with greater discernment. In our reading and what we choose to fill our minds with, let’s help each other strive for the higher road, selecting content that realigns our brain for the good. That strengthens rather than sullies our spirit.

Thanks again for this though-provoking article, Jasmine.

thought-provoking article…