184. How Can Nobledark Horror Explore the Problem of Evil? | with Marc Schooley

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 1:11:34 — 66.9MB) | Embed

This spooky season, what’s scarier than real-world evil? Imagine that Nazis are hiding in a prison mine where they try to torture their victims—that is, until a mysterious enemy in the dark forest rises up to destroy them with zombie-like plant creatures, a granite face, and supernatural symbols. Pastor and paranormal novelist Marc Schooley, author of König’s Fire, joins us to explore the problem of evil versus the amazing grace of our sovereign God.

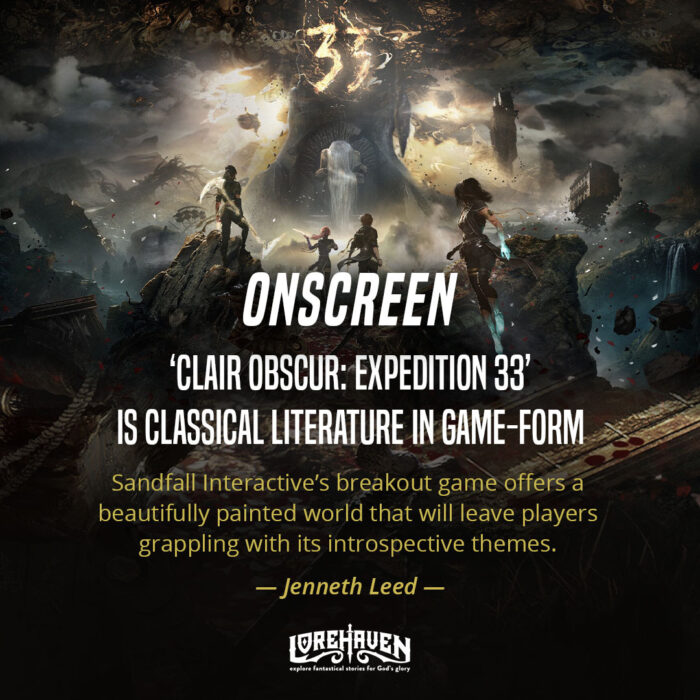

Subscribe to Lorehaven

middle grade • teens + YA • adults • onscreen • author resources • gifts • guild

Episode sponsors

- Oasis Audio: The Mermaid’s Tale by L. E. Richmond

- Almost Paradise by Bryan Timothy Mitchell

- The Lorehaven Guild: join monthly book quests through the best Christian-made fantastical novels

Concession stand

- Our other episodes defend/define some stories that are called “horror.”

- As we record, it’s Friday the 13th! Yet another portent of doom, or is it?

- Clearly this episode, like reality these days, covers darker subject matter.

- “See evil for what it is” may look different for people at different times.

- Sometimes you need whimsy, happy ideas, nostalgia, even distractions.

- But other times you need to confront evil so you seek answers in Christ.

- That’s what Konig’s Fire and its author help us explore, quite in-depth.

Introducing author and pastor Marc Schooley

Introducing author and pastor Marc Schooley

Marc Schooley is a Texan, Christian philosopher, theologian, and pastor of the Five Solas Church in League City, Texas. He also has twenty-three years experience in the space program for NASA Johnson Space Center, including work for the James Webb Space Telescope. His fantastical novels include The Dark Man, Konig’s Fire, and Nightriders.

1. What is the ‘problem of evil’?

If God is willing to prevent evil, but is not able to, then He is not omnipotent.

If He is able, but not willing, then He is malevolent.

If He is both able and willing, then whence cometh evil?

If He is neither able nor willing, then why call Him God?

—König’s Fire (2010), pages 21–22

- This tributes an 18th-century writer named David Hume, who goes on:

Why is there any misery at all in the world? Not by chance surely. From some cause then. Is it from the intention of the Deity? But he is perfectly benevolent. Is it contrary to his intention? But he is almighty. Nothing can shake the solidity of this reasoning, so short, so clear, so decisive.

—David Hume, Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, 1776 (yet published in 1907)

- Or as Lex Luthor phrases it (BvS, 2016): “If God is all-powerful, then He cannot be all good. And if he is all good, he cannot be all powerful.”

- Philosophers remind us that even the wisest minds find this challenging.

- Storytellers remind us that everyone confronts this in everyday suffering.

- As we record, you can look at the news and see people living this out.

- Even with Halloween decorations, people try to ignore/parody real evil.

- This gets even more complicated when innocent creatures suffer pain.

2. How does God’s word answer the problem of evil?

- Some people (even Christians) attempt to use reason over Scripture.

- We may be tempted to treat humans as passive actors in the problem.

- Ultimately we find our solution not in logical arguments but in the Bible.

- Some say Scripture shows God valuing human freedom > human good.

- Others say God values: His own glory = human good = human freedom.

- In other words, humans may be free, but our good God is always freer.

- God has decided to let us experience evil, to glorify Him by contrast.

- In effect, we might say that God does permit some kinds of horror.

3. How may nobledark horror help us see the truth?

- By “nobledark horror” we don’t mean slashers, violence porn, nihilism.

“Nobledark” would be a story in which there are genuine heroes, but the story world is full of terrors and gritty. An epic struggle for good and evil is ongoing, but the heroes are holding their own. Barely.

- König’s Fire would qualify as nobledark. Its darkness serves the light.

- Despite a lack of traditional “happy ending,” its heroes and God wins.

- Ultimately these stories help see beyond the present, to eternal future.

- They help us complete the story, hoping in the promises of Scripture.

- Romans 8:28–29 should be deep in our imaginations for hard times.

- As author Randy Alcorn notes, we study this now to prepare for later.

Open discussion

Mission update

- New review: Moonchild Rising by B. Ward Powers

- Coming article: How The Crucifix Shows Christ’s Salvation in Dark Fantastical Stories by Daniel Whyte IV

- Coming reviews: A Bond of Briars by Erin Phillips, Steal Fire From the Gods by Clint Hall and A Ranger’s Guide to Glipwood Forest by Andrew Peterson

- Subscribe free to get updates and join the Lorehaven Guild

Com station

Tom Darrow appreciated our ep. 183 critique of “banned” books:

This podcast does a good job covering the same semantic issue I did here, which is that “ban” is typically semantic overreach (which is used for marketing rather than meaningful communication.) Often the reality is that a book is being restricted from unsupervised access by children below a particular age, and that’s in no way a ban.

It’s also true that some books are genuinely harmful, or they advocate for harmful behaviors but can be read discerningly (to critique them) by a mature-enough reader. It absolutely makes sense to restrict these. Those who say they shouldn’t be restricted because we need to “break free” of “oppression” and we need children to be exposed to this content … well, they’re advocating for a social structure that I think is evil, and they’re advocating for indoctrinating children into that social structure. I think there are very few books that should be banned-banned-banned, like, nobody can interact with them — I basically put things like picture-books of actual sexual assault (including exploitation of children) into that category, and similar graphic depictions of other types of harm (like terrorist attacks) that basically function as violence-porn, and … not much else. I believe adults should be able to choose to read things like Hitler, Marx, Ayn Rand, or even the Unabomber’s manifesto. I don’t necessarily believe it’s *wise* to read certain things for certain people, but wisdom rather than authority should reign there.

Chapter 3 as a whole is very good. Particularly the commentary about how Amazon and others lack the “moral proportion” to make the decisions they’re making about books. And, of course, the commentary about how people encouraging the reading of “banned books” only want to encourage reading “banned books” from one specific political or cultural angle, and not reading controversial books from multiple sides. I never hear “banned book” people encouraging kids to read the Bible or Ayn Rand. They’re trying to put specific content into the hands of children, usually sexual or political content, rather than trying to encourage children to expand their horizons more broadly. The bait-and-switch is vile.

Next on Fantastical Truth

Twelve men on a boat are besieged by a storm. Suddenly they see, amongst the lightning, a spectral shape. Another man looks over a valley covered in skeletons. He speaks an incantation, and every single figure rises to life to form a great army. These images come directly from God’s word, but they’re likely not the most frightening accounts of the Bible. What then might be the scariest ghost story in Scripture, and why did God include this narrative?

Share your thoughts about this podcast episode