Perfect Characters Don’t Have to Be Boring

Once upon a time in grad school, I took a class on one of the longest novels in the English language: Clarissa (1748) by Samuel Richardson. Written serially in the novel’s first days as a genre, this 969,000-word monster tells the story of a virtuous young woman who gets kidnapped, manipulated, and eventually raped by the womanizing rake Lovelace. 1

In the beginning, readers find some sort of chemistry between the two. But by the novel’s end, as Clarissa continually resists his increasingly desperate attempts to win (read: force) her love, we find that this is obviously the bad kind of chemistry. The HAZMAT suit kind.

I was perplexed to find that nearly every other student in my class favored Lovelace over Clarissa. Again, this was Lovelace the kidnapper, the womanizer, even the rapist, for crying out loud. Even more surprising to me, the original 18th-century serial readers shared that sentiment: Richardson received droves of fan mail telling him to make Clarissa give poor old Lovelace a break.

Why?

Practically perfect in every way?

In short, Samuel Richardson set out to make Clarissa a morally perfect woman.2 Clarissa is virtually flawless, except for her mistake of initially trusting Lovelace). Whether by Richardson’s mismanagement or the human heart’s perversity, her high standards make her seem rigid, inhuman, and boring. Lovelace comes across as more relatable and interesting.

Readers often have this preference, don’t they? This why my students prefer Dickens’ Sidney Carton over Charles Darnay. It’s one of the reasons many critics of Milton’s Paradise Lost consider Satan the hero, not Milton’s version of God. It’s why Moses in Cecil B. DeMille’s film The Ten Commandments (1956) acts way more interesting before his encounter with God turns him into a stiff and distant figure.

Surely Christians, however, believe perfection is not boring, even if we feel bored to death by supposedly perfect characters. When we spend eternity discovering our infinite God’s array of perfections, we will certainly not be bored! We’ll be surprised, amazed, gratified, and flabbergasted: “He is even better than we dreamed!”

Thankfully, one notable author can write perfection in ways that rightly make this the most interesting picture on the page: C. S. Lewis.

Perfectly interesting fantastic fiction

Whenever Aslan appears in The Chronicles of Narnia, readers perk up. I lean forward expectantly, almost on edge. My kids? Well, let’s just say that when Aslan showed up the first time in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, one child jumped up and spun around the room, cheering, and the other buried her face in the couch and wept for joy.3

Aslan is never stiff. Never boring. Every word he speaks is power. Every action is electric. In a world where we often see perfection as vanilla, this mysterious and magisterial lion has crunch and flavor.

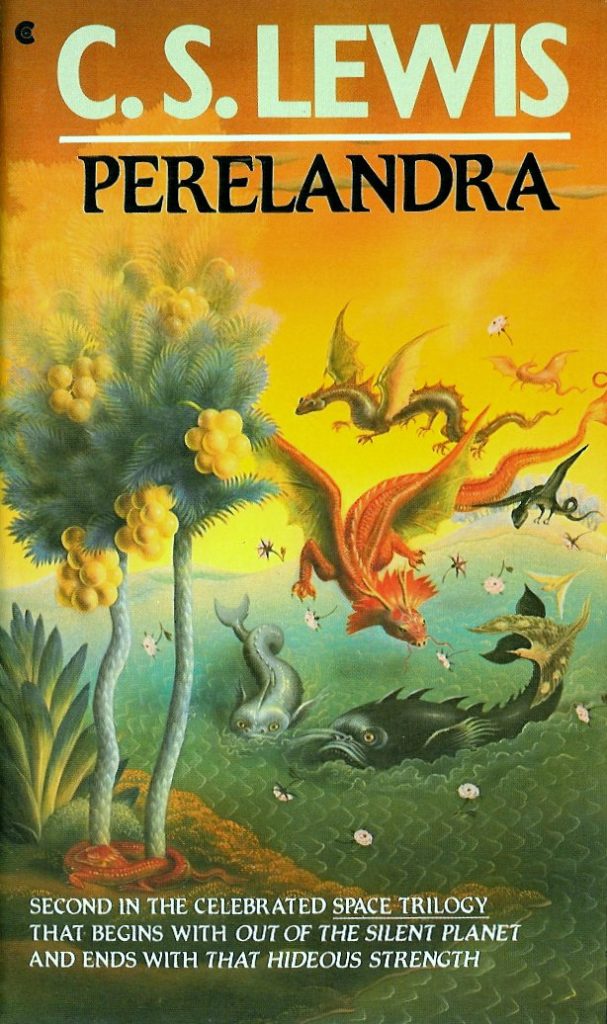

Although Aslan is the only God-figure we see most fully in Lewis’s writings, he’s not the only perfect character. We could also include the angelic Oyarsa from the Ransom Trilogy: beings who exist so beyond our perception that we’re forced to constantly stretch our brains to grasp them. The Malacandrian creatures, although their world has been touched by sin, are not themselves sinful. Therefore much of Lewis’s Out of the Silent Planet reads like a much more interesting, less infuriatingly preachy version of the yawn-worthy Houyhnhnm-land in Gulliver’s Travels.

Although Aslan is the only God-figure we see most fully in Lewis’s writings, he’s not the only perfect character. We could also include the angelic Oyarsa from the Ransom Trilogy: beings who exist so beyond our perception that we’re forced to constantly stretch our brains to grasp them. The Malacandrian creatures, although their world has been touched by sin, are not themselves sinful. Therefore much of Lewis’s Out of the Silent Planet reads like a much more interesting, less infuriatingly preachy version of the yawn-worthy Houyhnhnm-land in Gulliver’s Travels.

The Green Lady of Perelandra is also far more fascinating than your stereotypically sweet ingénue. She is gracious and noble as a queen, but she laughs like a child at Ransom’s appearance. The Lady is profoundly wise yet naïve. She is able to keep up with intense debates, but does not hesitate to halt the argument with “Hush! . . . let us listen to the rain.”4 Ransom finds her thought processes so alien and her conversation so challenging that, after their first interview, he wants “to run his hands through his hair, to expel the breath from his lungs in a long whistle, to light a cigarette . . . and in general, to go through all that ritual of relaxation which a man performs on finding himself alone after a rather trying interview.”5 Perelandra’s future queen is baffling, awe-inspiring, sometimes even infuriating—but she’s never once stiff or boring.

The perfection of perfection

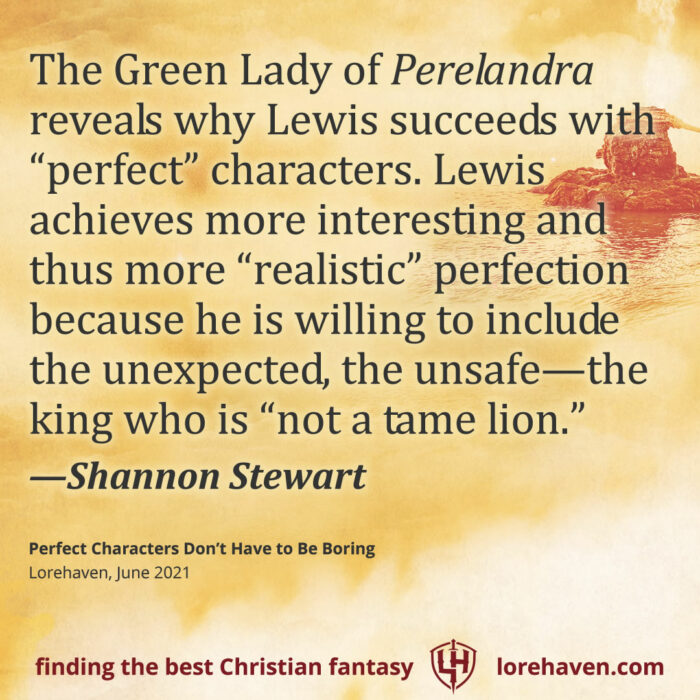

The Green Lady of Perelandra reveals why Lewis succeeds with “perfect” characters. Lewis achieves more interesting and thus more “realistic” perfection because he is willing to include the unexpected, the unsafe—the king who is “not a tame lion.”

The Green Lady of Perelandra reveals why Lewis succeeds with “perfect” characters. Lewis achieves more interesting and thus more “realistic” perfection because he is willing to include the unexpected, the unsafe—the king who is “not a tame lion.”

So many human views of perfection in this world are just that: tame. As fallen human beings, we can’t imagine perfection being dramatic or wild, because our own drama and wildness is sin-tainted. So we tone down perfection to our view of what good behavior includes—too often narrowed to the insufficient “avoid bad things.” For accuracy’s sake, we want to keep things safe and controllable. If we let it get out of hand, we might step outside the lines of perfection.

But Lewis shows Aslan doing the unexpected: Aslan lacerates Aravis’s back, cries with Digory, growls at Jill, and frolics with Susan and Lucy. He hangs out with Bacchus and trades jokes with Ravens. Against our safe versions of perfection, Lewis says via Mr. Beaver, “Safe? . . . Who said anything about safe? ‘Course he isn’t safe. But he’s good.”6

Lewis’s acknowledgement is profound: perfection would not be what our fallen minds expect. It’s consistent with Lewis’s other writing. In Mere Christianity, he says:

Reality, in fact, is something you could not have guessed. That is one of the reasons I believe Christianity. It is a religion you could not have guessed. If it offered us just the kind of universe we had always expected, I should feel we were making it up. But, in fact, it is not the sort of thing anyone would have made up. It has just that queer twist about it that real things have.7

“That queer twist that real things have”—this is why Lewis’s perfection is more real, and more satisfying, than most other literary attempts at showing perfection. It has that tang of the unexpected. It’s why Aslan puts us on the edges of our seats, why the Green Lady is such a baffling bunch of paradoxes, and why the sinless angels and aliens consistently confound Ransom.

Somehow we have been conditioned to expect that goodness is tameness. After all, in our pursuit of goodness, the Holy Spirit must tame so many wild thoughts and bad impulses in us. But Lewis knew that in reality, we find the ultimate source of goodness is the least tame and the least safe Source imaginable: He is “God Himself, alive, pulling at the other end of the cord, perhaps approaching at an infinite speed, the hunter, king, husband.”8 God is completely unexpected and more wonderful than our minds can stretch to hold. But perhaps our fantastic fiction can stretch to hold a more glorious perfection, full of unforeseen beauties and dangers, a perfection that more accurately reflects “a [perfection] you could not have guessed.”9

- Pronounced Love-less. Get it? ↩

- After his novel Pamela, which shows the virtuous woman getting rewarded with worldly success for her pains, Richardson wanted to show that virtue can and should continue even without hope of earthly reward. Whether he succeeded is debatable. ↩

- Yet another child was three and had wandered off to play with Legos. ↩

- Perelandra, Scribner, 1996, page 127. ↩

- Ibid, page 72. ↩

- The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Harper Trophy, 2000, page 80. ↩

- Mere Christianity, Harper San Francisco, 2001, pp. 41-42. ↩

- Miracles, Harper San Francisco, 2001, page 150. ↩

- Riffing on the Mere Christianity quote shared above. ↩

Thank you for writing this! So many good things to think about.

Thanks so much for your kinds words, Katie!

Thank you for this! “Perfect” characters get such a bad rap (often for good reason) that I’m really glad to see the good examples defended here!

Amen! Thanks for your comment. I’ve been percolating on why Lewis succeeds with perfection for a long time. 🙂

If you want to know how to write perfect characters… I have an idea.

What is the meaning of perfection? Why did a perfect God order a slaughter of entire nations? Will at times moral deeds bring bad consequences? Loving the Lord may mean at times violating conventional morality (I recommend reading Kiekengaard’s fear and trembling to get the idea).

I think one could study Vash from Trigun for a very good idea.